Hazardous life in coastal communities

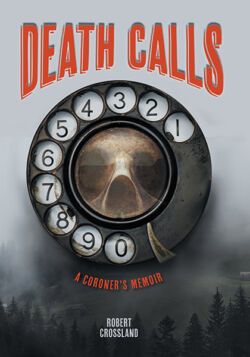

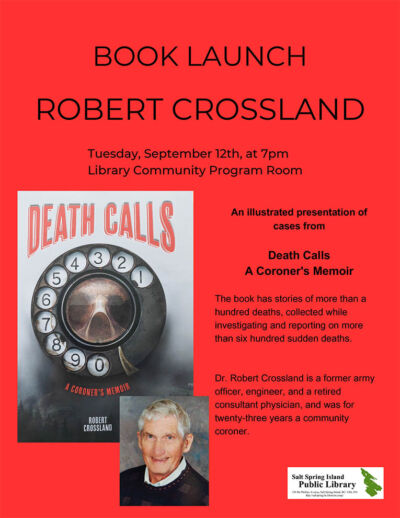

Death Calls: A Coroner’s Memoir

by Robert Crossland

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2023

$21.99 / 9781039168329

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

A book about the life of a coroner in the rainy northwestern coast may provoke moody murder mystery, with characteristics as dark and foggy as the climate in these parts. One might have certain expectations from a book like Death Calls, Robert Crossland’s memoir covering decades of experience as a rural coroner on the Sunshine Coast and Gulf Islands of British Columbia. Certainly, death plays an immense role in the literary imagination, and its potential as a topic for philosophical ponderings and metaphysical wanderings are nearly limitless. Crossland’s longtime and intimate exposure to randomised ends of mortality would, by all means, give him licence to wax poetic on death, yet his memoir is refreshingly upfront. His unavoidable wisdom is practical rather than abstract, being focused on relaying experience. Ultimately, Crossland’s memoir is engaging in its consistently honest descriptions of work dedicated to knowing the material and physical nature of death.

In its frankness regarding the investigation of death, Death Calls is a hypochondriac’s nightmare. The murder mysteries that one might hope to find stocked in the pages of a coroner’s autobiography are overtaken by the admittance that the vast majority of deaths are purely natural. This is not to say that Crossland’s cases are dull; very often, his stories are steeped in a mystery that is, in some ways, much more frightening than a serial killer on the loose. Indeed, the anticlimactic nature of an investigation into an unexplained death turning up little to no cause is enough to fill the reader with existential dread. The explained deaths may be just as uncomfortable. Crossland casually ruminates on the fact that many of his cases were the result of one or two moderate mistakes that, in a terrifyingly immediate manner, got out of hand.

An overarching sense of utility permeates Crossland’s writing, with an assortment of anecdotes covering cases organised by topical lessons and types rather than temporal or geographical location. As one of the relatively uncommon examples of a coroner who has medical training, Crossland is comfortable in an instructional setting. This is not to say that what Crossland has written amounts to an instruction manual, but rather that he vividly communicates the most crucial concerns for coroners in engaging in their duties. This includes graphic accounts of the handling of decomposing bodies, as well as the logistical nightmare of transporting said bodies from difficult positions. At times, the concerns are environmental, having to do with the rural wilderness settings of select cases. Whether rivers far out in the bush, logging camps miles from the nearest town, or seaside cliff-ledges nearly inaccessible for those without wings, Crossland’s daring is testament to the unsung courage expected of coroners in rural locations.

A coroner’s difficulties, as told by Crossland, do not end with the practicalities of reaching and investigating the scene of a death. Indeed, a cynical reader may find a fair amount of incitement in Crossland’s descriptions of the system governing the British Columbia Coroners Service and the aftermath of such investigations. The latter half of the book features in-depth descriptions of a coroner’s inquest, which is a form of special investigation that resembles a trial in many ways. However, Crossland’s experience with said inquests, which culminate in certain recommendations given to the parties involved in an applicable case, are coloured by the fact that many times the recommendations go unimplemented. This fact, along with that the majority of coroners in British Columbia lack the medical training that Crossland, as a consultant physician, has himself, is aggravated by the lack of adequate pay for coroners. Regarding the inquests, Crossland mentions how he actually loses money by participating. Readers may be surprised to learn about the lack of overtime paid to a person expected to cross rivers and mountains in order to rescue a deceased person. Death Calls is not an indictment of the system, but rather shows the struggle and dedication involved in the endeavour to know the cause of death in a community.

Crossland indeed supplies an intriguing way of learning about the communities of which he has been a member for over two decades; not by discussing social, political, or cultural features, but rather through the ends of many of the community members. His proximity to death, as relayed so explicitly in detail, gives a view of the countless everyday hazards in the life of many residents of coastal communities in BC. Whether workplace accidents or recreational mishaps, from loggers crushed by trees to divers falling victim to careless behaviour at great depths, the reader is given an original perspective on life in these communities through the stories of so many deaths.

The difficulties of the coroner’s profession in coastal British Columbia are not solely related to the discomfort of such consistent interactions with death and grief, they are also rooted in the logistical difficulties of physically reaching the bodies of the recently deceased in rural locales. In rural coastal BC, the actual job of determining cause of death is compounded by the fact that, when that death has occurred in the bush, reaching the scene may be a death-defying stunt in its own way. Filled with practical wisdom and engaging anecdotes, Crossland’s writing is petrifying in the way it seizes the reader with his casually graphic descriptions of the physical and emotional realities of death. For those seeking to learn more about the coroner’s profession, or those wanting a to learn a new perspective of coastal communities by reading of how their community members die, Death Calls is a candid yet thought-provoking read.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey is an independent writer and researcher based out of Victoria, British Columbia. He has degrees from UVic (BA hons) and the London School of Economics (MSc) [Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also recently reviewed books by Donna (Yoshitake) Wuest with Joe W. Gardner, Mike Whalen, D.C. Reid, Alexander Globe, Angus Scully, David Giblin, and Bill Arnott for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “Hazardous life in coastal communities”