Elite art collecting demystified

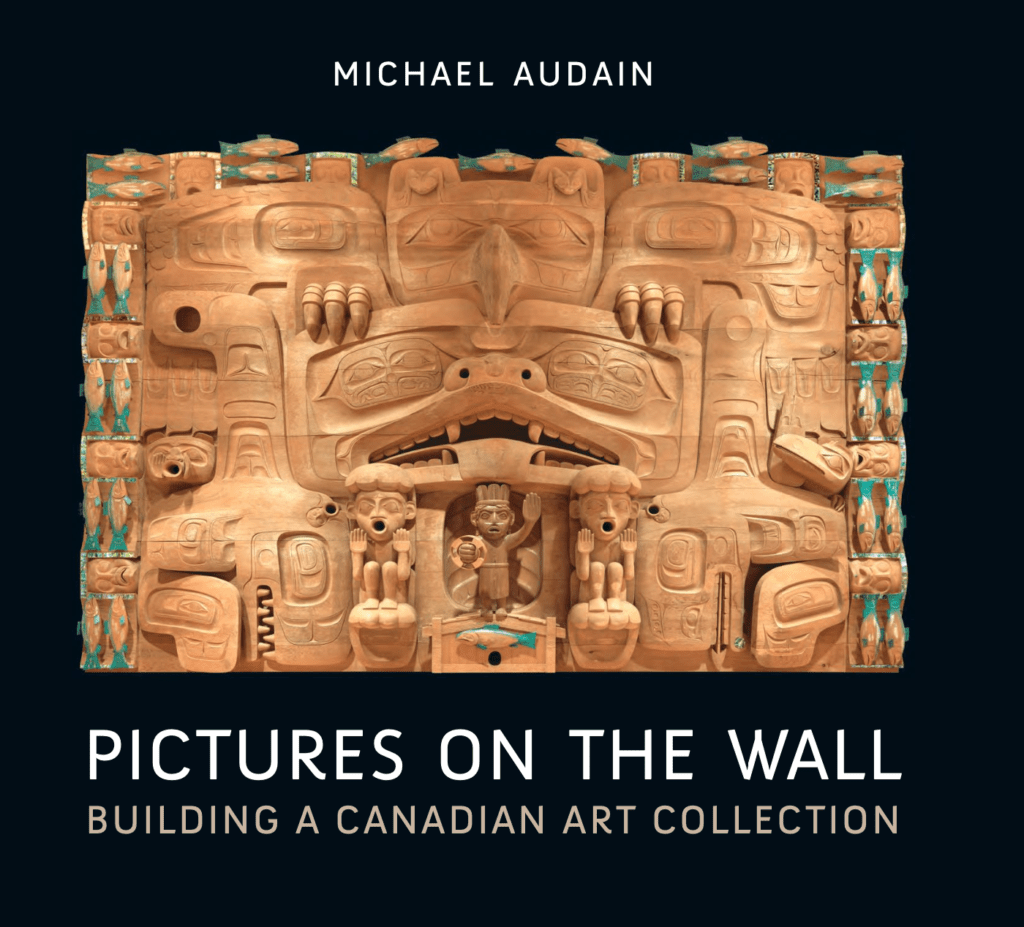

Pictures on the Wall: Building a Canadian Art Collection

by Michael Audain

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2023

$60.00 / 9781771623742

Reviewed by Trevor Marc Hughes

*

On the evening of November 14, 2002, I walked through a chilly downtown Vancouver, MiniDisc recorder and microphone safely tucked away in a shoulder bag, toward my destination: the Sheraton Wall Centre on Burrard Street. There I was to capture as much relevant sound as I could of the art auction being held by Heffel Fine Art Auction House. I was working for CBC Radio’s The Arts Report (when there was such a thing) and had my tip-off from the Toronto arts desk as to which major Canadian works of art were to garner the greatest dollar figures. On the top of my list: a Lawren Harris oil painting and one of his sketches. Also work of Emily Carr and Bill Reid were expected to get record-setting offers. I plugged in to the house sound, took my seat in the large conference hall, faced the auctioneer’s podium, and sat, poised with my pen, to scribble down the selling prices for these major works of Canadian art. The bidding, of course, was done anonymously, some representatives at the event held up cards to indicate bids, others were bidding by phone. By the end of the evening, I had my story: In the Ward – Grocery Store, oil on canvas, by Lawren Harris sold for $600,000 and his Tumbling Glacier, Berg Lake went for $195,000 (then a record amount for a Harris sketch). Also, Emily Carr’s Somewhere, oil on paper on board, went for $120,000 (well above asking price – a bidding war ensued), and Bill Reid’s 1984 bronze sculpture Killer Whale sold for over $275,000 after the dust had settled. I didn’t stay to hobnob, I strode diligently back into the night to Hamilton Street to file my story, but as I walked there was a nagging doubt in my mind that I’d missed the real story. Sure, I got the dollar amounts, the economic value among collectors for what these works were worth, but I wouldn’t discuss the art itself, nor, more importantly, to whose collections they would be added. Did Ken Thomson get his prize? Perhaps an unknown collector from overseas was punching the air in celebration? Or, just maybe, Michael Audain had added to his growing collection.

Michael Audain’s Pictures on the Wall: Building a Canadian Art Collection explains a great deal about what has driven him to collect major works of not only Northwest Coast and Canadian art but also artwork from further afield. Audain is a self-described “home builder” (a proud real estate magnate, chairman of Polygon Homes Ltd., certainly a man of these times). After a somewhat obsequious foreword by former director and CEO of the National Gallery of Canada, Marc Mayer, readers are reminded that artists need philanthropists.

“Much of my life…” is how Audain begins, in what would seem from the outset a vanity project, but this book turns out to be a deep dive into what makes a collector tick, and persist in collecting, whether it be at auction, or by word of mouth.

Many fascinating questions arise through Audain’s stories. Can anyone truly own a piece of art? What is the difference between ‘art lover’ and ‘collector?’ Does the collecting of Indigenous art fall into the category of appropriation? With tongue firmly in cheek, Audain states an old chestnut he admits applies to him: “I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.”

Another old chestnut is “if you’ve got it, flaunt it,” and with Audain’s prodigious wealth, why not chase after what he likes? He takes us back to where he developed his appreciation for art: as a boy visiting the British Columbia Provincial Museum (now the Royal British Columbia Museum) which gave him “an introduction to the art of the original people of the Northwest Coast (although it wasn’t considered true art then).” Many influential art gallery visits in his teens would fuel his interest in art from around the world and his first wife would also play a role in encouraging his “habit” of collecting. Why collect art? “The most common motive for acquiring a work of art is no doubt simply decorative,” Audain notes, “to accent a living space.” Art appreciation is a driver in collecting as well, as is investment and the pride of discovery, but eventually, in the collector’s opinion “the process of collecting becomes a passion in itself, and you have to start thinking about what you’re doing.”

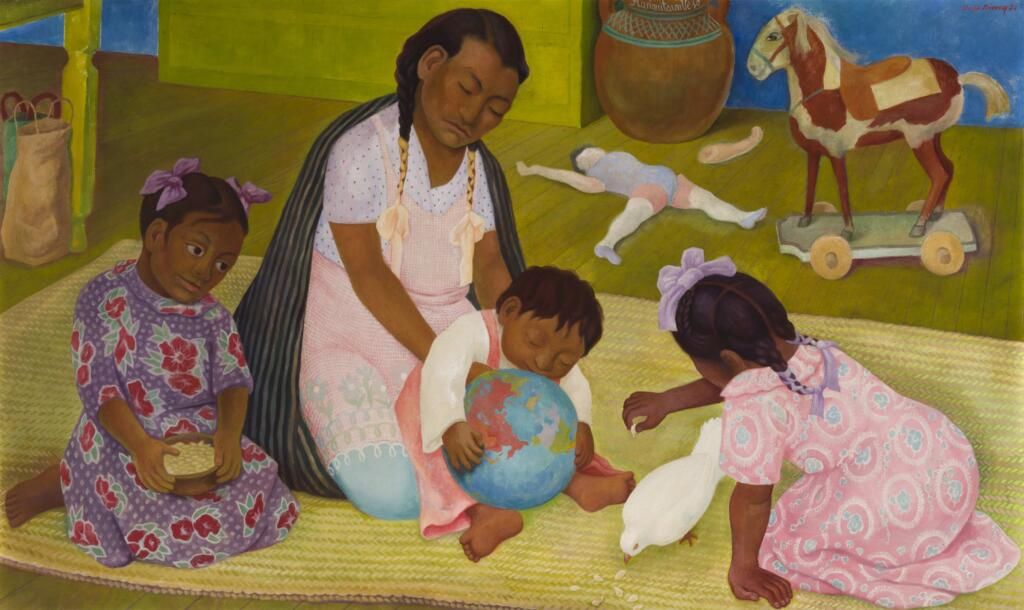

He considers his art collection narrow, as is outlined in his chapters: British Columbia art, Mexican Modernists, Quebec Automatistes, and a smattering of bric-a-brac. But the stories behind the works and how he came to collect them are truly of interest to art appreciators.

Audain exclaims with pride the high “aesthetic standard” of the works represented in ‘Art of the Northwest Coast.’ Works in Audain’s collection have been made from argillite, yellow cedar, and red cedar, range from poles to masks, and originate with artists from Charles Edenshaw to Robert Davidson. Chest, c. 1800-50 by an unknown Tsimshian artist presents an example as to a work that has returned to these lands from a collection that went far away from its place of origin.

This bentwood box became part of the collection of “the Reverend Robert J. Dundas, a Scottish missionary who journeyed up the British Columbia coast in 1863 and acquired a great many Tsimshian treasures from the missionary William Duncan of Metlakatla, who had obtained them from his converts.” The quality of the carving and paintwork must have appealed to Audain, as he “stumbled into owning” the box, which eventually went on display at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler.

The reader stands to gain from Audain’s experience. He admits to not knowing much about Northwest Coast Art when he began collecting works such as Chest, but over time he appreciated the significance of this work. Value can be found in the lessons, guidance, and knowledge he gathered from works in his collection. A question remains: What does it mean to own a piece of art?

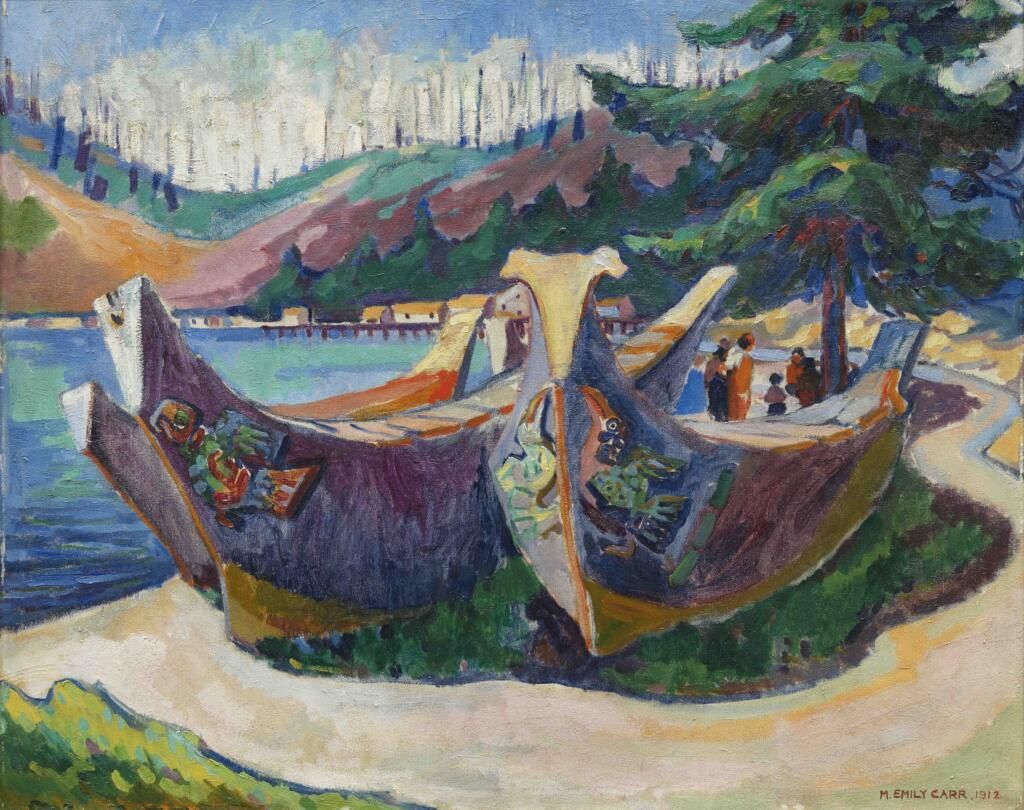

War Canoes, Alert Bay, 1912

oil on canvas

84.0 x 101.5 cm

Audain Art Museum, Whistler, BC

Image courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

Audain moves to Emily Carr. He chronicles her as “ridiculed outcast” and, eventually, “world-class artist.” He praises her work for “evoking a dynamic union between land, sea and sky” and notes the incorporation of French Post-Impressionism into her paintings, marking the European influences into landscape painting in her time. But she would also show her appreciation for the Indigenous peoples of the new colony. Audain mentions Carr was “instrumental in according Indigenous art the respect it lacked for so long.” War Canoes, Alert Bay, 1912, combines French painting technique with First Nation subjects, after her return from France, showing a change in her style. In the telling of how he acquired the painting, Audain admits his bid for the work set a new record (in May 2006) for a price paid for an Emily Carr. He also expresses that mainstream media only consider art news when it fetches a hefty price at auction, usually trying to hook readers questioning the well-being of wealthy art collectors. He backs this up with the story of how, just after the auction, when he and his wife were travelling by taxi in Victoria, the driver exclaimed how Carr “used to walk around Victoria pushing a baby carriage with a dog and monkey in it…but there’s someone even crazier in Vancouver who a couple of weeks ago paid over $1 million for one of that woman’s paintings.”

Indeed, this perception of the mental instability of elite art collectors is a pervading one. Nonetheless Audain persisted in his collecting, and the work he collects sometimes has a personal value associated with it. The Coastal Steamship “Princess Victoria,” 1965 by E.J. Hughes is demonstrative of his “picturesque scenes of the British Columbia coast.” It also shows, in surprising detail for an oil painting, an image of the very steamship Audain sailed on from Vancouver to Victoria in 1947 “en route to a new Canadian life.” He also was touched by what he saw as Hughes’ influence taken from Mexican muralists (Mexican Modernists would feature prominently in a later chapter).

The Coastal Steamship “Princess Victoria,” 1965

oil on canvas

76.2 x 121.9 cm

Private Collection

Image courtesy of Equinox Gallery

A whole chapter is devoted to Jean Paul Riopelle, and his mosaic painting. One work acquired through a dealer in New York City is without a title, but Sans Titre, 1949, had Audain paying a high price. It is exemplary of the kind of competitive price-driving seen among an elite pack of art collectors. Audain was proud of having beat Canadian collector Andre Desmarais to the punch on this one, after this “remarkable” Riopelle was nearly overlooked by he and his wife, Yoshiko Karasawa.

What becomes clear is that, in order for a work to become prominent, whether during or after the lifetime of the artist, the artist requires a benefactor. That’s a hard fact to shake. E.J. Hughes was fortunate to find Max Stern of Montreal’s Dominion Gallery, for example. Audain has, as a collector, brought up the profile of certain artists whose style he finds aesthetically pleasing, but he also is driven within a social milieu. Art collecting is, in the end, a social enterprise. Although never explicitly admitted, the work’s value is determined within a particular social, political, and economic context. Aesthetic, like fashion, is but passing fancy. What wealthy collectors like Audain collect is a chronicle of the times.

He is not always successful in his bidding (he admits he was once outbid for a Frida Kahlo by Madonna), but much of what he has managed to acquire can be seen at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler. The building’s architecture and design are featured at the end of the book, as is a full list of works in Audain’s collection.

There is no doubt that this book gives the reader a privileged glimpse in to an elite world, but Audain concludes that art collecting is not just a pastime of the very rich. Developing an appreciation for art comes from attending museums and galleries, and artwork can be purchased by beginning collectors at manageable prices.

“It is important to remember,” Audain stresses in conclusion, “we never really ‘own’ a work of art; we are merely its temporary custodians before passing it on to future generations.” What Audain has passed along, is a lifetime of art appreciation and collecting, and a chance to see the trajectory of an art collector, from a boy attending a museum, to a wealthy philanthropist and art appreciator who is revealing his identity, going beyond his anonymity in the hallowed space of the art auction venues.

Maternidad (Motherhood), 1954

oil on canvas

92.6 x 156.9 cm

Private Collection

Image courtesy of Ward Bastian Photography

*

Trevor Marc Hughes worked for a decade at CBC Radio Vancouver (1997-2007), half of that time filing stories for The Arts Report. He has written several books and many articles about his motorcycle travels across British Columbia. He edited Riding the Continent, Hamilton Mack Laing’s account of his 1915 ride on a Harley-Davidson 11-F across the continental United States. He’s the author of Capturing the Summit: Hamilton Mack Laing and the Mount Logan Expedition of 1925. He is currently the interim non-fiction editor for The British Columbia Review and has reviewed books by John Vaillant, Peter Rowlands, and Daniel Arnold, Darrell Dennis, & Medina Hahn.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster