1889 Wealth, family, and the ‘spectrum of female suffering’

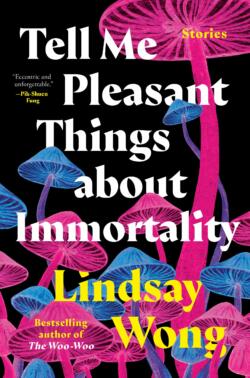

Tell Me Pleasant Things about Immortality

By Lindsay Wong

Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2023

$32.95 / 9780735242364

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Probably the West’s most iconic piece of short fiction begins with a shock: an office clerk wakes up one morning to discover that he has been inexplicably transformed into “vermin” (usually taken to be a cockroach or beetle). The rest of the story records the consequences of this change—escalating mental and physical pain, grotesque decay, and cruel family abuse, all leading to a darkly humorous but gruesome climax. The story, many will immediately recognize, is “Metamorphosis” by German-speaking Czech author Franz Kafka. In many of the stories in her collection, Tell Me Pleasant Things about Immortality, Vancouver-raised writer Lindsay Wong echoes this disturbing narrative line while passing it through the filter of her Chinese heritage.

Probably the West’s most iconic piece of short fiction begins with a shock: an office clerk wakes up one morning to discover that he has been inexplicably transformed into “vermin” (usually taken to be a cockroach or beetle). The rest of the story records the consequences of this change—escalating mental and physical pain, grotesque decay, and cruel family abuse, all leading to a darkly humorous but gruesome climax. The story, many will immediately recognize, is “Metamorphosis” by German-speaking Czech author Franz Kafka. In many of the stories in her collection, Tell Me Pleasant Things about Immortality, Vancouver-raised writer Lindsay Wong echoes this disturbing narrative line while passing it through the filter of her Chinese heritage.

Indeed, so unified is the collection that for many readers a central interest could well be seeing how the author—like a jazz musician perhaps—takes a set of motifs and, through her imagination, works them in almost dizzying variations.

Most of the stories, in fact, spiral out from one or two extraordinary premises specific to the story. In the very first story, for instance, a father turns into a high-kicking dancer—and confessed serial killer. Elsewhere, a woman is granted eternal life—until at 380 years old, she starts to fall apart (literally). In a third, offspring are sold as meat, their sad memories somehow making them particularly tasty, while their throats are crammed with magic leeches. A few pages on, a kind of “internet-order bride” brings the apocalypse to North America. In another tale, quite simply, after shooting himself, the speaker’s “father turned into a sofa.” An apparently “realistic” account of a worker in a psychiatric prison takes a completely different tack when the speaker becomes “a full-time human ATM machine,” money pouring out of “almost every orifice in my body.” In perhaps the most suspenseful story, the protagonist tries to escape from a deadly job in a ghastly underground mushroom farm until, after a futile attempt at escape, he discovers he is turning into food for yet more mushrooms. In “Sorry, Sister Eunice,” the protagonist and all but one of her sisters disguise themselves as American college sorority members, all the better to eat “human gristle.”

By this point, terms like surrealism, magic realism, absurdism and fantasy vie with each other to best describe how Wong is working. Yet none of these terms quite captures the way Wong consistently channels these surprising eruptions into a steadily developed narrative line.

A further alert: those readers who like their literary flights of fancy to be delightfully whimsical might want to take their reading time elsewhere. Wong’s imagination is about as rough and tough as it gets. The strong-stomached reader can revel in astounding flourishes of dismemberment, decay, agony, torture, and so on, all washed down with bodily fluids and excrement. In spite of the sheer brio of the writing, we might be inclined to believe the author’s claim in her Acknowledgements, “It is a ghastly undertaking to write a book….”

Though innovative from some angles, in the most basic, structural ways, her stories are nevertheless traditional. Most of her stories—of roughly conventional length—follow the course of a fixed period of a central character’s life, and build, via a twisted sort of “suspense,” toward an eye-popping climax. Take the following example of one such climax:

“Gritting my teeth, I lunged at the madam’s witchy visage, and we plunged to the burgundy floor as one blurred monstrosity. Her lopsided pupils expanded like two dirty yellow moons, revealing her hideous surprise. Elbowing her ghastly face, I used my hands to pull the half-squealing leeches that clung to my chin and shoved the creatures down her puckered throat.”

Not all the stories end with quite the same nightmarish fireworks, but most do end, not with a whimper, but a bang.

An additional characteristic of Wong’s writing will be all too apparent from this example—her ability to conjure up detail upon detail upon detail. While barely a paragraph goes by without such jagged bursts of detail, what Wong does with food is especially wicked as, for example, she describes “pork fried rice, the sunny-side eggs bleeding into stringy bok choy and semi-frozen turkey that tasted like toilet paper.”

Comparing turkey to toilet paper is funny. Indeed, readers with a particular sense of humour will find that the author is repeatedly enthusiastic (as she was in her memoir, The Woo-Woo) about dishing up humour, and especially adept at the humour of incongruity and bathos. “Red-Tongued Ghosts,” probably the funniest story, conjures up both aplenty: “The first few times Xiang tried to strangle someone with her lizard tongue, she missed and knocked over a dresser.” The story concludes, “After she throws the burnt bodies into the boiling water, she might take a leisurely splash in the Very Hot Suicide Spring. She might sit under father’s tree, maybe learn to crochet or take up day trading.”

But what, the intrigued reader might ask, is to be made of this rich mayhem of mixed tones? Like most writers who have kicked themselves free of “realism,” Wong often seems to hint at allegory. While any strong allegorical parallels are, at best, elusive, clear principles do emerge. Indeed, it is tempting to feel that these stories are “about” much that deeply concerns the author. Something they are clearly “about” is the role of women, especially but not exclusively in the context of Chinese social values.

In the first place, female beauty—or ugliness—is at the very core of several stories. At one extreme, “Ugliest Girls” is a nightmarish tale devolving from the implications of being born ugly: “my harelip has always been fierce and unapologetic, my eyes like misshapen mouse turds. My long, uneven braids dangle like parasites; my mouth pinched like a rotted lotus flower.” At the other extreme of the spectrum of female suffering in the name of “beauty” is the last story in the volume, “A Bloodletting of Trees.” Here, the infamous tradition of “lotus” foot breaking and binding among late Imperial noble girls becomes a horrific ghost story: “more tortoise than girl, Yuchen began to crawl on knees through the white, sepulchral trees….”

Unsurprisingly, the social value of a woman’s beauty, as Wong shows, is next door to its commercial value. In one way or another prostitution permeates the stories: “In China, all poor girl are prostitutes,” we read at one point; at another “In Houtouwan, girls must swim or sell their bodies.” And so on.

In such a context, it is hardly surprising that nearly every story contains at least one reference to suicide. “I’d probably want to kill myself for becoming less attractive,” exclaims the protagonist of the apocalyptic “Sinking Houses,” her particular drive to suicide shackled to the need for beauty. Suicide and suicidal impulses play into virtually every storyline, notably in the story where the protagonist witnesses her “father shoot himself over a bowl of soggy rice noodles.”

The particular vulnerability of women, in turn, is interlinked with the push for wealth. As much as any of the other forces driving the storylines, poverty on the one hand and greed on the other hamstring just about every human impulse. In some stories the issue underlies a gritty and banal realism, especially in the North American stories, where in one, “Wreck Beach,” Wong’s protagonist reports, “We were the poorer Chinese, not like those rich ones who had come from Beijing with money and cars and maids … the kind that white Vancouverites liked, boosting up the economy.” Worse, in rural China, extreme poverty leads to cases where, for example, “The Yangs are rich and they ate three girls….” It is basic to the principles of money in these stories that “No one rich has ever been called ugly,” just as it is that ugly girls can be called “money making cows.”

Clearly, the stories are in some ways “about” Chinese culture and the Chinese experience. In many different ways Wong draws on iconic Chinese cultural elements. Buddha in one context or another is mentioned in most stories. Chinese history can reach back to the Han Dynasty or, in the twentieth century, can appear in the form of the Japanese invasion or Tiananmen Square. In the North American context, Wong makes narrative spice of a great-uncle “who had come with the other Chinese in 1881 to build the continental railroad.” Or, more generally, she paints a dreary picture of the immigrant experience, where one protagonist can suffer from a “neurotic immigrant work ethic,” or another find herself on the outskirts of Chinatown in a house of “hideous grey cardboard that matched the overcast sky.” In this immigrant context “Chinglish” becomes both funny and sad. Says a protagonist’s mother, “They’re smarter than mouse. Are you smarter than mouse? No you just stand there and not move so your heart so bad.”

As the instrument of oppression, the family, in Wong’s stories, is—almost always—relentless. Uncles and aunts, cousins, brothers and sisters, and, most of all, parents are rarely anything more than the source of pain and suffering. And yet, almost startling, in all the darkness and bitterness a few shafts of light illuminate poignant moments of affection especially striking amongst family members. Xiang, the protagonist of “Red Tongued Ghosts,” “can’t help but feel a fierce outpouring of love for [her father]. In his life as a human Father was generally a peaceful household figure, indulging the whims of his wife and daughters.” It makes, in fact, a fitting reminder of the extraordinary unpredictability of these otherwise (often literally) ghastly stories that one of them, “Sinking Houses,” should end movingly, with a memory of the protagonist and her mother: she “grabbed my hands and spun me around and around…. As we whirled under towers of green horse chestnut trees, the staring people became shapeless blurs. Until slowly, one at a time, they slipped off our own private planet, leaving my mother and me, unperturbed.”

It is difficult not to feel that in this concluding sentence Lindsay Wong has touched on what, in many ways, though utterly uncharacteristic of the tangled, dark stories in the volume, reveals something significant about her understanding of the diversity of human experience.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at the University of Victoria. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Bill Engleson, Dan Gawthrop, Lyndon Grove, Ihor Holubizky, & Brent Raycroft, David Fushtey, Aaron Bushkowsky, Devon Field, Pirjo Raits, and Vince Ditrich for The British Columbia Review. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1889 Wealth, family, and the ‘spectrum of female suffering’”