1769 Filtering adult stratagems

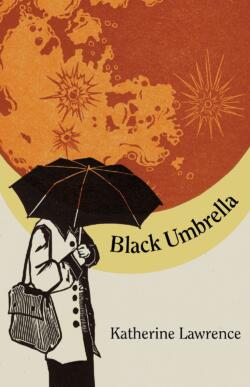

Black Umbrella

by Katherine Lawrence

Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 2022

$18.00 / 9780888017475

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

How much do readers of poetry want, let alone need, to know about other people’s intimate family lives? Fiction has always explored the domestic world, but poetry…? Whereas in English language poetry it was fine for male writers to strut their erotic stuff, traditionally women poets have been allowed to bare their hearts, but nothing more. Everything else was sanitized or suppressed. But women poets have come a long way in the past sixty years.

How much do readers of poetry want, let alone need, to know about other people’s intimate family lives? Fiction has always explored the domestic world, but poetry…? Whereas in English language poetry it was fine for male writers to strut their erotic stuff, traditionally women poets have been allowed to bare their hearts, but nothing more. Everything else was sanitized or suppressed. But women poets have come a long way in the past sixty years.

This is due in part to the emergence of so-called Confessional Poets (a label never adopted by the poets themselves) which had its origins in 1956 in Ginsberg’s Howl. Even if Howl itself contained more boasting than confession, thereafter no language was too crude and no hitherto taboo subject matter was off limits. It was followed by Robert Lowell’s Life Studies (1959), by W.D. Snodgrass’s Heart’s Needle (1959), and then by the work of Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, and in Canada by Margaret Atwood’s Power Politics (1971).

Katherine Lawrence’s latest work then has a powerful provenance. Most of these poems provide a closeup of fraught family relationships witnessed by the poet over the long haul. What she evokes in the motifs of the mother’s continual affairs and the much loved but absent and later remarrying father could so easily have been “confessional,” but it is not. Time and again she impresses by the confidence and dexterity with which she absorbs, adapts, and repurposes these influences as the ground bass for her own very individual ends. The rawness of the situations and the strength of the mixed feelings involved, even decades later, are filtered through her own adult experience of parenting and held at a distance by irony, careful framing, and a kind of wit not too common in Canadian poetry.

Part of the effectiveness derives from her frequent use of the prose poem — roughly half by my page count. Whether singly or in sequences, its more expansive form allows for greater explanation than would be comfortable in a more traditional poem and so enables Lawrence first to hint at and then, by an accumulation of carefully observed details, to build towards an insight or a revelation, as here in “The Beautiful Mother,” where she realizes that during the teacher-parent meeting he7r mother, a professional model, and the male teacher have:

… moved to a place I can’t reach. Worse, I’ve lost

her scent to something animal, something not-my-mother, her

pupils glowing inky black as the signature she scratches on the

back of my report card.

Similarly in the poem that follows this, “Liminal,” also a sequence of prose poems, she presents us with a situation where she is ostensibly playing with her younger sister while her mother is cooking. She notes:

……………………………………………chrome faucets turning hot

cold. My ears tuned to sound waves under water. Warm tones

dripping from Mother’s voice. Her special friend. The secret

itches my nails, bites my lower lip, itches behind my knees, the skin scratched raw. Little Sister doesn’t know. Our Dad doesn’t

know. Cannot, not ever. Promise? I promise.

In her highly charged world of childhood memories almost everything becomes symbolic. Thus, a science class about tectonic plates and the Ring of Fire carries over into a dream about a Japanese girl reacting to the first tremors of an earthquake. It is hard not to see this as a premonition of the domestic earthquake of her parents’ impending separation and the two sisters having to choose which parent they wanted to live with.

But throughout the book her poetic effects are measured and calculated. Sometimes it seems as if every phrase is invested with double meaning, though without losing its intensity or spontaneity. I was continually surprised and delighted by Lawrence’s control of the minutely observed but emotionally significant detail, as when, surveying the detritus following her dead father’s wake, she notices “carrot sticks dried at the ends and curled like beckoning fingertips,” while in “Vows and curses,” about her father’s wedding to a woman of Italian background, after telling us of the traditional Italian wedding treat of sugar coated almonds, to “symbolize the bittersweetness of marriage,” she focuses on her mother alone at home as she:

untied the treat, lifted the candy to her lips, tongue, teeth, bit

down hard, winced in pain. A back tooth. Cracked.

Damn him. Damn them both to hell

Here as elsewhere Lawrence demonstrates her finely honed ironic sense. Indeed the whole book resonates with a steady ironic counterpoint between appearances and the underlying reality.

So too, even without the occasional allusion to Emily Dickinson, we find a comparable intensity of imagination, as here in “Can’t get the smell of smoke out of my hair”:

This is the trouble with dreams and dying,

the dream roams from dark to light while the

dying go dark. Two separate piles of laundry.

None of these skills would matter, however, were the reader not totally convinced of the genuineness of the persona that is so precociously and critically aware of the stratagems employed by the adults around her, especially her mother, and of her own responses:

The way I pretended a stranger dialled

the same wrong number, night after night

It works because her critical awareness of others is balanced by an equally clear-eyed introspection. Thus in “The heart wants,” one of the finest in the book, after wondering why she kept her future husband waiting ten years before accepting his proposal, she decides:

…………………..The better question is this:

what took me so long? I was more rabbit

than girl in those days, small game

sensing danger

and ends:

What was the matter? Not a thing. I needed time,

time to fall in love with my body, my voice, my

brave, surefooted, animal self.

Such poems build up a reader’s confidence in the poet’s judgment of others, so that ultimately what emerges is a carefully balanced and nuanced childhood portrait of both parents, including their divorce and subsequent remarriages as filtered through her own adult experience as a parent. No sacred cows invade Lawrence’s poetry. She sees, and remembers what she sees and is prepared to talk about it.

Other than a minor quibble over the inclusion of the three “list” poems, I find Black Umbrella a triumph of controlled nuance. But above all it is in the best sense constantly provocative. It provokes us to consider complex and ambivalent feelings, and arises not from a desire to shock but from a need to tell it as it is, not to provide answers but to stimulate further questions.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. The most recent of his thirteen books of poetry are A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017) and Small Talk (Silver Bow, 2022), reviewed here by Al Rempel. He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series. Editor’s note: Christopher Levenson has recently reviewed books by Leanne Boschman, Isa Milman, H.C. (Hans) ten Berge, John Barton, John Pass, and Rob Taylor.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1769 Filtering adult stratagems”