1735 The matter of Snair & Weasner

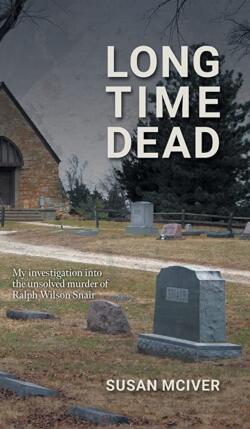

Long Time Dead: My Investigation into the Unsolved Murder of Ralph Wilson Snair

by Susan McIver

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2022

$14.99 / 9781039151123

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

The great advantage a fictional murder mystery has over a true crime saga is that in fiction the detective always gets his man. Oh, okay, there was that Morse episode in which they said they just couldn’t figure it out (which was appalling!), but generally speaking in novels and TV series you get your puzzle and the satisfaction of a solution (though solutions are always a letdown, aren’t they? all that build-up and then, It was them?).

The great advantage a fictional murder mystery has over a true crime saga is that in fiction the detective always gets his man. Oh, okay, there was that Morse episode in which they said they just couldn’t figure it out (which was appalling!), but generally speaking in novels and TV series you get your puzzle and the satisfaction of a solution (though solutions are always a letdown, aren’t they? all that build-up and then, It was them?).

But in a true life account there sometimes isn’t an “It was them?” moment. There’s no satisfaction, no solution. I can remember watching episodes on the Zodiac killer, which always seemed to be building up to a solution, but then in the end there was nothing. It was sad.

Here, too. Susan McIver, originally from Kansas, but later a coroner in British Columbia, decides to look into the death of her great-uncle, Ralph Wilson Snair, found dead in a rented car by the side of a Kansas highway, a bullet in his head, in 1957. A very cold case. Too cold. It’s not even clear if it was murder or suicide, but why would he have killed himself? But why would anyone have killed a harmless senior citizen who did odd jobs and lived alone?

The problem is, we don’t know enough, and for all her probing and going over what has survived of the evidence, Susan McIver is not able to come to a resolution. She seems to end up thinking it was murder, but it’s not that clear why, and she has to speculate about motive. His pockets were turned inside out and his empty wallet was found nearby, but robbery doesn’t seem convincing. Was he transporting drugs or something else contraband? But what? There was a mysterious Mr. Weasner he said he was going to see; did that have anything to do with it?

But no one was ever able to trace Mr. Weasner, and the police gave up after following a few other leads: the cross-dressing burglar, the violent son of Ralph’s landlord, a local vagrant.

The best part of the book is finding out about Ralph, how he grew up in rural Kansas, with several siblings who went to college and became teachers (or a nurse), but he never finished high school, always wrote his postcards in pencil, served as a stretcher-bearer during the First World War until he was gassed just ten days before the end, then ended up in various sanitariums — for post-traumatic stress? Or was it for something else? The autopsy showed signs of a vasectomy, and he was at a clinic associated with treating people practising “deviant” sexual behaviour. What exactly was going on with Ralph? Who was he, really?

In fictional murder mysteries, often it’s the victim’s life that gives the biggest clue, but here we know so little of the life. One might think the author might know more about her great-uncle, but who ever knows their great-uncle? “Nothing is known with certainty,” says the author, and she means about the killing, but it is true more broadly. Ralph Snair was a private individual who never married or started a family, held a series of odd jobs, never really settled down, and then he was gone. Perhaps the most dramatic part of his life was the way he left it, and was that a decision on his part? Was it suicide? But he is just one of scores of thousands (or millions) who pass this way and are gone. Not everyone makes it into Wikipedia.

With so little known about Ralph’s life and his death, what might have made for an interesting book would have been if the author had recounted the story of her investigation. We get the results here, the forensics, the letters from police officers to the family, but it might have been more interesting if Susan McIver had taken us along on her actual journey, into the records, interviewing anyone who is left (but there doesn’t seem to be), travelling to Kansas.

But in the end we just have notes on the investigation, and no solution, no resolution, just a great-uncle dead in rural Kansas sixty-five years ago.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017), reviewed by Herbert Rosengarten. He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember, (Bristol: UKA Press), was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. His latest book, Sherlockian Musings: Thoughts on the Sherlock Holmes Stories (London: MX Publishing, 2019), was reviewed in the BC Review by Patrick McDonagh. Originally from Montreal, Sheldon has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies. Editor’s note: Sheldon Goldfarb has recently reviewed books by James Gifford, Alan Twigg, Yosef Wosk & Nachum Tim Gidal, Andrew Chesham & Laura Farina, Seth Rogen, and Julia Levy, and he has contributed a comedic poem, The Ramen, based on Poe’s “The Raven.”

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1735 The matter of Snair & Weasner”

What’s the matter with this reviewer? The title of the book says it’s about an unsolved murder. Why did he bother reading it?

I am tempted to read the book, even though the reviewer says, “But in a true life account there sometimes isn’t an ‘It was them?’ moment. There’s no satisfaction, no solution.” At my advanced age, I can handle not knowing something, especially something that, in this case, was taken to the grave 66 years ago.