1704 Turtle Island chronicles

Our Homes on Indigenous Lands: Stories of My Ancestors Across Turtle Island

by Mali Bain

Surrey: Hancock House, 2022

$24.95 / 9780888397416

Reviewed by Ken Favrholdt

*

Our Homes on Indigenous Lands: Stories of My Ancestors Across Turtle Island is a deceptively lean book about family history but entails a broad canvas that spans over 300 years from Great Britain to Turtle Island, set against the background of colonialism on the continent. Analytically, author Mali Bain takes her cue from the work of Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies, Victoria Freeman’s Distant Relations: How My Ancestors Colonized North America, and others.

Our Homes on Indigenous Lands: Stories of My Ancestors Across Turtle Island is a deceptively lean book about family history but entails a broad canvas that spans over 300 years from Great Britain to Turtle Island, set against the background of colonialism on the continent. Analytically, author Mali Bain takes her cue from the work of Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies, Victoria Freeman’s Distant Relations: How My Ancestors Colonized North America, and others.

Our Homes on Indigenous Lands is a remarkable book that will attract a large following of Canadians and Americans who have a deep immigrant background. Turtle Island, of course, is a term that applies to the continent as a whole that comes from an Anishinaabe/Ojibwe creation story (p. 13). Bain, who lives on Snuneymuxw (Coast Salish) territory in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, weaves a narrative across thousands of miles from Kenya (a British settler colony where Bain was a volunteer teacher) to Jedediah Island to Prince Edward Island, and to Vancouver.

Mali Bain writes in a very personal, distinctive way. Between profiles of family history she describes the history of Indigenous relations with the settler population. It is what author Bain calls a “place-based approach” – combining place, possession, and people to her narrative. Her writing style is a blend of intimate, detailed family history, and the history of those areas where her family settled.

The narrative is divided into three parts: Jedediah Island (BC), Epekwitk (PEI), and back to Coast Salish Territory.

Bain proves she has an exceptional knowledge of the historical background to her family’s story, including significant aspects of colonial and Indigenous history to tell the story of European settlement in North America and the dispossession of Aboriginal homelands.

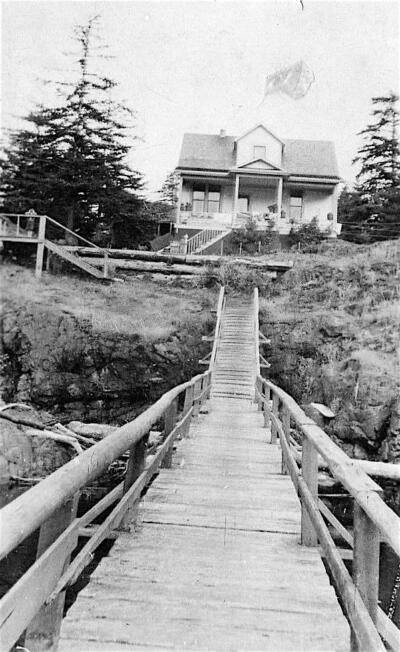

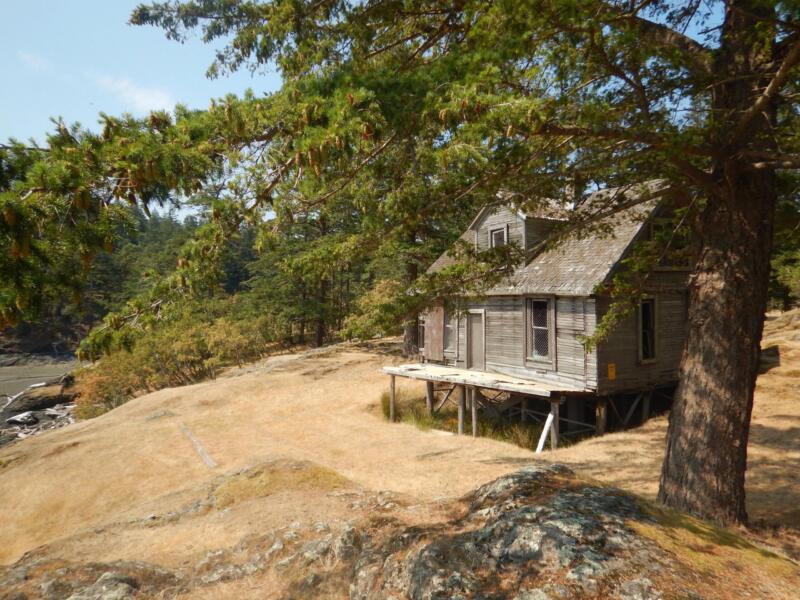

Bain’s narrative begins on Jedediah Island off the coast of British Columbia with the Foote side of her family. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is the datum to the unceded lands of what is now British Columbia where her ancestors settled what had been the traditional territory of the Tla’amin Nation for thousands of years. “Yet in 1890 [when the Footes arrived on the West Coast] the Government of British Columbia issued a title deed for Jedediah without even a gesture toward a negotiation, settlement or discussion with the local nations” (p. 27).

Mid-way through the book, Bain turns from the Jelly-Foote branch of her family to the Bain-Barker side. Her Bain ancestors settled on Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island) the Mi’kmaq name meaning “resting on the waves” (p. 76) where they had lived for thousands of years. Bain describes the history and the loss of land by the Mi’kmaq who were increasingly marginalized by first French and then British

colonial presence. William Bain at 27 years came with his parents to New Brunswick in 1834, then to Prince Edward Island where William, trained as a stonemason, helped build the Colonial House, now Province House in Charlottetown, the site of Canadian Confederation.

Bain married Ellen Dockendorff and the Bain clan grew from two to 50 by 1900. Francis Bain, William and Ellen’s second eldest son, became an amateur botanist and studied natural history on Epekwitk. At times, Mali Bain’s descriptions strain to make a connection between the white and Indigenous peoples. Of Francis Bain’s peregrinations of Prince Edward Island, Bain ponders, “Despite the lack of records, I wonder if, in his adventurous excursions when he encountered a Mi’kmaq group, he might have exchanged pleasantries and a bit more, in mutual appreciation of the beauty of Epekwitk” (pp. 93-94).

Returning to the story of Jedediah Island, Mali Bain recounts how Harry Foote was born in England and immigrated as a child with his parents John and Mary Ann to Ouentironk on Lake Simcoe, the home of the Wendat. Harry, in his early twenties left for Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, where he met a woman with his mother’s first name; they married in 1882. He became a real estate agent.

Harry and Mary Ann Foote arrived at Vancouver from Portage La Prairie in 1890. Bain describes the new city and the history of the Coast Salish people. Harry Foote worked as an insurance agent, a secretary for City Fuel Company and, by 1900, for a parcel delivery company. The Footes built a comfortable house (still standing) in the Mount Pleasant area of Vancouver as well as their home on Jedediah Island.

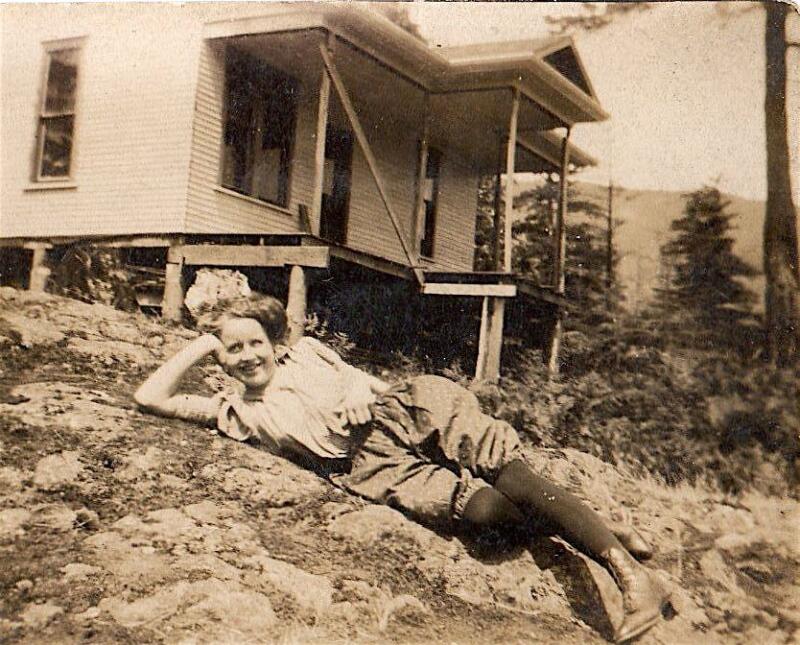

It was in 1909 that Morris Jelly of Jellyby, Ontario, met Harry and Mary Ann Foote’s middle daughter, Winnie. By the spring of 1910, Morris and Winnie were married. After some trying years, in 1920 they sold Jedediah to Englishman Henry Hughes; the island was then owned by several absentee landlords, and finally by Mary Palmer, author of the book Jedediah Days: One Woman’s Island Paradise (Harbour, 2007) and like Bain a resident of the Nanaimo area.

In one of the final chapters including letters from Jacob Bain, son of the first Bain to Turtle Island, to his son Will Bain living in Ranfurly, Alberta, Bain detects “the commonly held views of the time,” of racist exclusionary policies against Chinese, Japanese, South Asian, and Indigenous peoples. “And yet, the ‘British’ Columbia he experiences was formative in creating the present-day life I live on Coast Salish territory,” Mali Bain reiterates. “My task is to understand and challenge the ways in which those patterns continue to manifest in my own time” (p. 160). Jacob lived in Vancouver’s Kerrisdale district with his daughters Mabel and Nell.

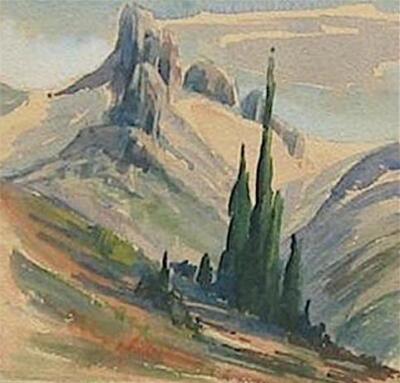

Bain includes much about the life of the Bain aunts, Mabel and Nell, during the 1910s and twenties in BC’s major city. As a schoolteacher in Vancouver, Nell did not have Indigenous students; Bain compares her situation with the residential schools in Mission and Lytton, and the harm they caused. Mabel Bain, a milliner or hat-maker, was best-known for her painting career that flourished at the same time as her more eminent contemporary Emily Carr was capturing West Coast scenes.

Mabel and Nell moved to Fort Langley in the 1920s. Bain recounts that, ten years earlier, the McKenna McBride Commission had met the Chief of the Langley Band who told the Commission:

Today I am telling you that I own the land… — the white men have taken our land and we have never got anything.

During Governor Seymour’s time [1864-1869]… we were told that the Governor was going to give us some more land and give us reserves, and he said that the Government was going to pay the Indians for the outside lands and that was in his speech … since that speech was made, we never heard anything more about it, and I am tired waiting now for compensation from the Government (p. 164).

In conclusion, Bain states, “Colonization is interwoven into the fabric of my and my family’s presence on Turtle Island, past and present” (p. 191). Her ancestors had originated from only a few countries, all on the European continent. None were descended from slaves in the Americas and none were Indigenous. But Bain situates her background at every turn against that of a number of Indigenous peoples to reveal the history of dispossession of land and the privilege of white people. Yet Bain’s family history does not intersect directly with Indigenous people. Here, in Our Homes on Indigenous Lands, is the story of many immigrants to the New World.

Mali Bain’s family history is just one of many that have unravelled their impact across Turtle Island. I look at my own family journey from postwar Denmark to Vancouver, and then my own wanderings to other places I have lived in BC where I became interested in native culture and made many connections with Indigenous peoples. This is the message behind Mali Bain’s book: “understanding where I come from — and thus who I am — as part of finding ways to “unsettle the settler” within myself” (p. 15). Bain hopes that other readers will do the same.

Decolonization is part of the process of reconciliation that will build bridges across the chasms that have separated Indigenous people from their ancestral lands.

Mali Bain has included the Jelly and Bain family trees and many personal black & white photographs that bring life to the story, as well as Mabel Bain’s painting of Howe Sound from West Vancouver’s Lighthouse Park.

*

Ken Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, four at the Osoyoos Museum, and he is now Archivist of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and a commemorative history for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken has undertaken research for several Interior First Nations and is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold rush journal of John Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. He lives in Kamloops. Editor’s note: Ken Favrholdt has recently reviewed books by Liz Bryan, Erín Moure & Anne Callison, Jeannette Armstrong, Lally Grauer, & Janet MacArthur, Arthur Manuel & Ronald Derrickson, and Clarence Louie for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1704 Turtle Island chronicles”

This is a wonderful review. I am only part way through this book but can attest to how thoughtfully and heart-fully it is written. Mali Bain reflects on where and who she comes from with a depth of integrity. She acknowledges the dilemma of having her family’s history placed at the centre of this narrative. It’s a challenge that she meets with care, and the result is a family history that includes an honest look at colonization, privilege and land dispossession. I have a fantasy of high school and university students being given a similar project to map out their own histories in this kind of way. This is a book that manages to be both informative and moving. I am looking forward to continuing my reading.

Very good review! I will be looking for this book. I definitely relate to this concept: “understanding where I come from — and thus who I am — as part of finding ways to “unsettle the settler” within myself” (p. 15 Mali Bain).

A beautiful concept and a lovely review. Thanks.