1675 A catalogue for the ages

The Bob Dylan Albums 2nd Edition

by Anthony Varesi

Montreal: Guernica Editions, 2022

$34.95 / 9781771837590

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

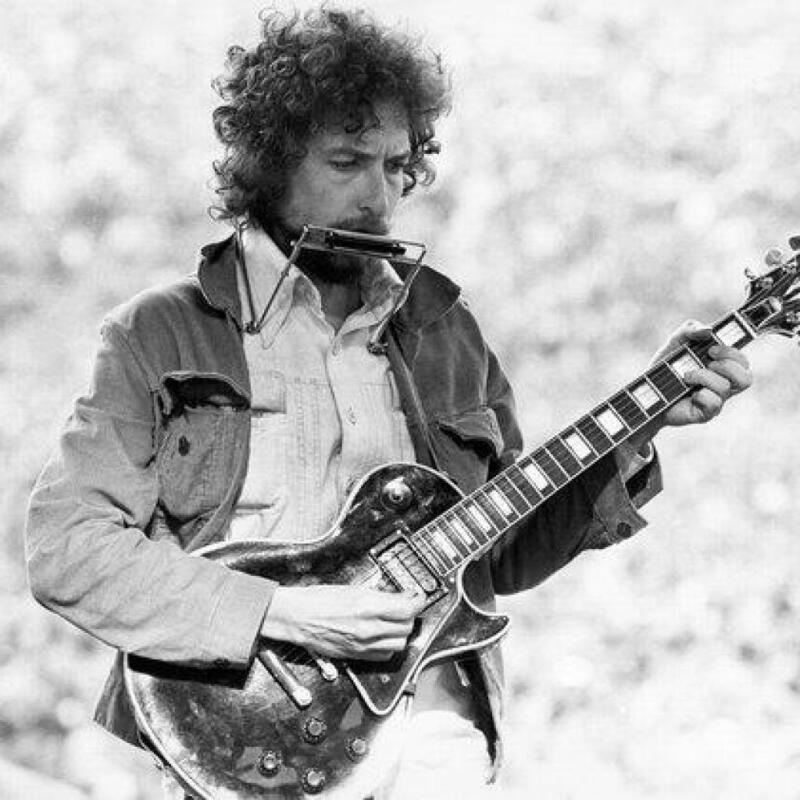

In the autumn of 1964, a precocious Bob Dylan — who had just released his fourth studio album at age twenty-three — told a writer from The New Yorker that he was moving on from “finger-pointing songs” about what’s wrong with the world, already transitioning to more deeply felt, introspective material. “Me, I don’t want to write for the people anymore,” the former Robert Zimmerman explained. “You know — be a spokesman.” This was a shot across the bow at singer/songwriters like Phil Ochs and Pete Seeger, left-wing folkies whose topical approach to composition, in Dylan’s view, made their work more like journalism than art. The implication — that protest songs would not survive the times in which they were written — seems ironic now, given that Dylan in fact did quite a lot of musical “finger-pointing” over the next six decades.

In the autumn of 1964, a precocious Bob Dylan — who had just released his fourth studio album at age twenty-three — told a writer from The New Yorker that he was moving on from “finger-pointing songs” about what’s wrong with the world, already transitioning to more deeply felt, introspective material. “Me, I don’t want to write for the people anymore,” the former Robert Zimmerman explained. “You know — be a spokesman.” This was a shot across the bow at singer/songwriters like Phil Ochs and Pete Seeger, left-wing folkies whose topical approach to composition, in Dylan’s view, made their work more like journalism than art. The implication — that protest songs would not survive the times in which they were written — seems ironic now, given that Dylan in fact did quite a lot of musical “finger-pointing” over the next six decades.

The New Yorker interview is just one of hundreds of Dylan factoids in this book, a massive tome encompassing the entirety of his recording career — including all studio albums and official live recordings, bootlegs, boxed sets, and greatest hits compilations up to Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020). The fact that this second edition comes twenty years after the first — and, according to Kamloops This Week, was almost entirely rewritten, expanded from 65,000 to 150,000 words — is a tribute to its subject’s indefatigable spirit: while archival material keeps cropping up and is still in demand, Dylan, now 81, has somehow produced enough new material since 2002 to warrant a second edition. Oh, and that 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature probably helped, too.

*

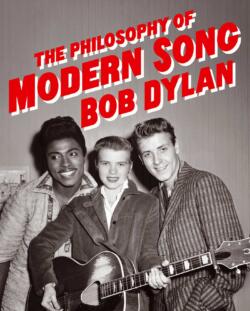

The timing for this book couldn’t be better. Dylan has just come out with The Philosophy of Modern Song, his first book of new writing since 2004’s Chronicles: Volume One and, of course, his first since winning the Nobel. A deep dive into the nature of popular music that took him more than a decade to write, Dylan’s new book is a collection of more than sixty essays about songs by other artists that covers everyone from Hank Williams to Nina Simone to Elvis Costello. With The Bard himself taking such a deep dive into the world of modern song writing (“He analyzes what he calls the trap of easy rhymes, breaks down how the addition of a single syllable can diminish a song, and even explains how bluegrass relates to heavy metal,” says the dust jacket blurb), it makes sense that a volume about his songwriting would be published at the same time.

When it comes to B.C.-based Dylanologists, the name that usually comes up is that of Victoria poet, critic, and scholar Stephen Scobie (Alias Bob Dylan, Alias Bob Dylan Revisited, And Forget my Name: a Speculative Biography of Bob Dylan). But Varesi, a Kamloops-based crown prosecutor by day, seems to have carved out a niche by focussing on Dylan’s body of work. And oh, what a body: nearly 600 songs and 40 studio albums since 1962, when the young troubadour began what New Yorker editor David Remnick recently called “one of the great explosions of creativity in the twentieth century … song after song in a kind of fever dream that lasted until 1966,” making Dylan “an antenna of the Zeitgeist.” In the fifty-six years since then, we’ve seen sporadic moments of creative brilliance between periods of inactivity or funk in which it is never quite clear which Bob will show up.

Putting it all together in a single, comprehensive reference guide must have been a massive undertaking the first time, never mind a second. But Varesi, who began listening to Dylan at age 12 and has seen him in concert fifty times, has proven more than up to the task. It’s all here: from the Woody Guthrie-inspired early material and three of the greatest albums of all time (Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde, which include the likes of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “Ballad of a Thin Man,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “I Want You”), followed by the Basement Sessions with The Band, the country period (“Lay, Lady Lay”), Blood on the Tracks, the born-again Christian period (Slow Train Coming, Saved), the Eighties and Nineties (Infidels, Knocked Out Loaded, Time Out of Mind), to the more recent original work (Modern Times, Tempest, and Rough and Rowdy Ways, which after its release in 2020 made Dylan the first artist to have an album in the Billboard Top 40 in each decade since the 1960s), and classic song interpretations (Shadows in the Night, Fallen Angels, Triplicate).

But this is by no means a book of lists. Varesi covers the entire Dylan catalogue, providing thoughtful analysis of every important song, its musical and literary merit, and its enduring potency through live performance and adaptation following its original recording. From 1967’s John Wesley Harding, here’s his take on “All Along the Watchtower”:

Dylan has played the song live over 2,200 times, making it his most performed song — not necessarily a positive, given the often rote versions Dylan has trotted out over the years. The song has been covered by many artists, with Jimi Hendrix’s version from 1968 the most laudable of them all. And while Hendrix undoubtedly transformed the song into an electric musical masterpiece, neither Hendrix nor anyone else (including Dylan himself) ever quite recaptured the eerie, apocalyptic atmosphere of the original two-and-one-half-minute acoustic version, with Dylan’s harmonica playing matching all the foreboding of Hendrix’s guitar work.

For Blood on the Tracks (1975), the album marking Dylan’s return to the song writing power of his mid-1960s material, Varesi recounts the musical artist’s move from California back to New York City to study painting under the artist Norman Raeben. After spending five days a week for two months with Raeben, the painting lessons altered Dylan’s sense of time and narrative while composing music. This made a difference, Varesi notes, for songs like “Tangled Up in Blue,” which Dylan felt freer to rewrite over the years. In concert, he notes, “Tangled” is now “one of Dylan’s most overplayed songs, always bringing howls of recognition from audience members unattuned to the more recent offerings Dylan often works into his setlists.”

In commenting on musical and literary influences — and what was going on in Dylan’s life as he composed some of the most canonical songs of the twentieth century — Varesi reminds us of The Bard’s deeply religious sensibility. Biblical references are everywhere in Dylan’s work, long before and since his born again period, and his literary and film influences range from Blake to Whitman and La Strada to Rebel Without a Cause. Fittingly, Varesi’s commentary on the songs is often complemented by notes on the many films produced about Dylan, from D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back (1967) to Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home (2005).

Like some of the bootleg recordings from the period Varesi is reviewing, these films cover Dylan’s life during the same period, despite not being released until many years later; through his commentary on them, Varesi deftly layers the recording period with more context. In capturing Dylan’s versatility, the book also reminds us of the dizzying array of musicians who have recorded and/or performed with him, from Joan Baez to the Traveling Wilburys, and the countless jazz, blues, and country musicians who have also shared his stage or studio. These collaborations, of course, all contributed in some way to the development of Dylan’s repertoire and musicianship.

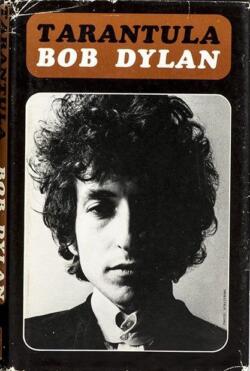

Dylan’s prose writing also figures into the mix. Varesi describes Tarantula (1971) as “an amalgamation of images, ideas, and personages (some real, some fictional), with an almost total disregard for narrative structure…” It was, he concludes, “an uninteresting stream of consciousness muddle.” Chronicles, Volume One (2004), the long-awaited Dylan memoir, was much better. Calling it the literary event of the year, eclipsing new releases by Philip Roth, David Mitchell, and Alice Munro, Varesi says the book is “compulsively readable,” especially in its weaving together of fact and fiction. Throughout it, he notes, Dylan recalled episodes and individuals in his life that have stymied all researchers’ attempts to verify. (This, I assume, was the Trickster in Dylan: the iconoclast resisting all attempts to pigeonhole him, just as he resisted early attempts to build him up as a spokesperson or tear him down as a “Judas” for going electric at the 1965 Newport festival.) Chronicles, says Varesi, “takes its place among Guthrie’s Bound for Glory as the rare music memoir that holds up as a distinguished work of literature.” No doubt, he will have much to say somewhere about The Philosophy of Modern Song, this year’s big literary event of Dylanalia.

*

Careful to avoid the hagiographic zealotry of the hard-core fan, Varesi in his observations presents a balanced portrait of his idol. Along with praise for the classic material, great performances and inspired collaborations, there are plenty of critiques of lousy concerts, inferior recordings, and simply bad songs. Dylan’s performance of “Chimes of Freedom” at Bill Clinton’s inaugural ball in 1993 he describes as “execrable” and “John Brown” as one of Dylan’s “poorest anti-war compositions,” its conclusion “overly cruel and inauthentic.” Not surprisingly, Varesi reserves some of his harshest criticism for Dylan’s later work such as Tempest (2012), whose quality and listenability were diminished by excessive song length, Dylan’s declining vocal ability, and the treatment of his musicians as “little more than skeletal backing.”

Nor does Varesi shy away from Dylan’s more controversial behaviour. From the failure to credit musicians for certain songs he mined for his own material, to selling out to Starbucks and other artistic compromises unworthy of The Voice of a Generation, the book presents an objective assessment of this most complex personality. Like the rest of us who are awestruck by the sum of Dylan’s achievements, Varesi, too, was disappointed by his response after winning the Nobel: waiting until the last moment to deliver his acceptance speech for the award — just in time to accept the US$900,000 that came with it — only for a Slate reporter to discover that he had lifted his discussion of Moby Dick in the speech from Sparks Notes.

Five years earlier, there was the much-criticized tour stop in China. Dylan was pilloried in the U.S. media after subjecting his set list to state censors and failing to perform more protest songs. In this case, Varesi sides with Dylan. “Far from kowtowing to or implicitly endorsing a repressive regime,” he says, “Dylan’s trip to China was nothing more than one more stop on the Never Ending Tour slate.” Much of that tour, he adds, “seems like an excuse to see as much of the developed or developing world as possible, a worthy endeavor that Dylan has largely accomplished, journeying to any number of far-flung locales.” Such tour dates, he can’t help mentioning, include 2017 stops in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan and Dawson Creek, B.C.

*

My only quibble is the lack of an index. Given the relevant, often fascinating background details for each album — proving Varesi made good use of that 17-page bibliography — I was eager, after putting down the book, to revisit various references to musicians, songwriters, and other cultural influencers and events sprinkled throughout the text.

Whether you’re a Dylan-is-God worshipper or merely a dabbler like me, you’ll find much of interest here. Well-informed, even-handed, and decently written, this updating of the Dylan oeuvre is a worthwhile and highly readable addition to the canon.

*

Daniel Gawthrop has seen Bob Dylan in concert only twice, both times in Vancouver: in 1986 with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and in 2012 with Mark Knopfler. He is the author of a forthcoming novel, Double Karma, which will be published in Spring 2023 by Cormorant Books, and five non-fiction books including The Trial of Pope Benedict: Joseph Ratzinger and the Vatican’s Assault on Reason, Compassion, and Human Dignity (2013), and The Rice Queen Diaries (2005), both published by Arsenal Pulp Press. Visit his website here. Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has also reviewed books by Corey Hirsch, Harley Rustad, Karen Moe, Keith Maillard, Hassan Al Kontar, and Cheryl A. MacDonald & Jonathon R.J. Edwards for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1675 A catalogue for the ages”

I enjoyed this review!