1674 A literary kingdom

Try Not to Be Strange: The Curious History of the Kingdom of Redonda

by Michael Hingston

Windsor, ON: Biblioasis, 2022

$24.95 / 9781771964159

Reviewed by Michael Hayward

*

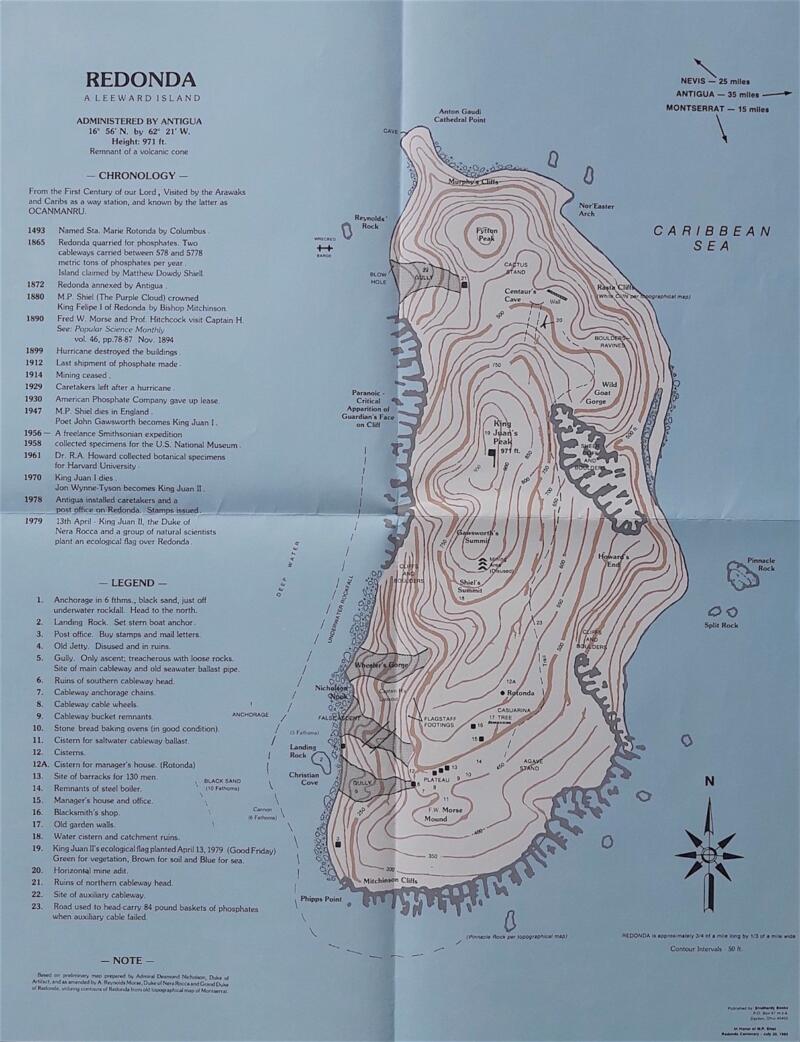

1100 km beyond Haiti in the western Caribbean, west of the British Virgin Islands and just visible from the tiny island of Monserrat, lies an even smaller, uninhabited island named Redonda, one of the Leeward Islands, and part of the sovereign state of Antigua and Barbuda. Despite its isolation and its nearly barren state, Redonda boasts a past which might be the envy of islands many times its size. For this guano-spattered speck of land is much better known — in certain spheres, at least — as the Kingdom of Redonda, and a succession of lesser-known literary figures have, since 1865, ruled as its King, while a host of more celebrated writers have been named as the Kingdom’s royal courtiers. Among these ennobled literary luminaries are Lawrence Durrell, Dylan Thomas, A.S. Byatt and Ray Bradbury — as well as Canada’s very own Nobel Prize winner, Alice Munro, named in 2005 (by King Xavier I of Redonda) as the Duchess of Ontario.

1100 km beyond Haiti in the western Caribbean, west of the British Virgin Islands and just visible from the tiny island of Monserrat, lies an even smaller, uninhabited island named Redonda, one of the Leeward Islands, and part of the sovereign state of Antigua and Barbuda. Despite its isolation and its nearly barren state, Redonda boasts a past which might be the envy of islands many times its size. For this guano-spattered speck of land is much better known — in certain spheres, at least — as the Kingdom of Redonda, and a succession of lesser-known literary figures have, since 1865, ruled as its King, while a host of more celebrated writers have been named as the Kingdom’s royal courtiers. Among these ennobled literary luminaries are Lawrence Durrell, Dylan Thomas, A.S. Byatt and Ray Bradbury — as well as Canada’s very own Nobel Prize winner, Alice Munro, named in 2005 (by King Xavier I of Redonda) as the Duchess of Ontario.

Who, after first learning of the existence of this obscure Caribbean micronation — an island with literary pretensions, no less — would not want to read the complete, and completely fascinating, story of how it all came to be? Now, with the publication of Michael Hingston’s Try Not to Be Strange: The Curious History of the Kingdom of Redonda, you need wait no longer.

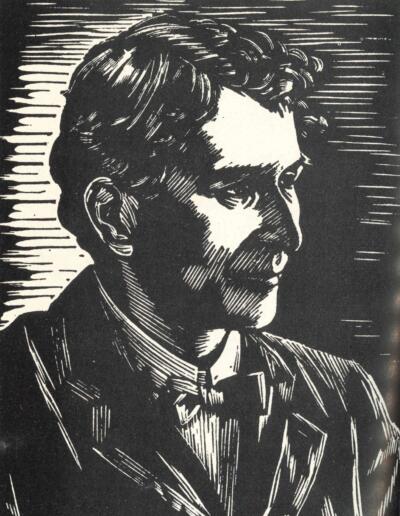

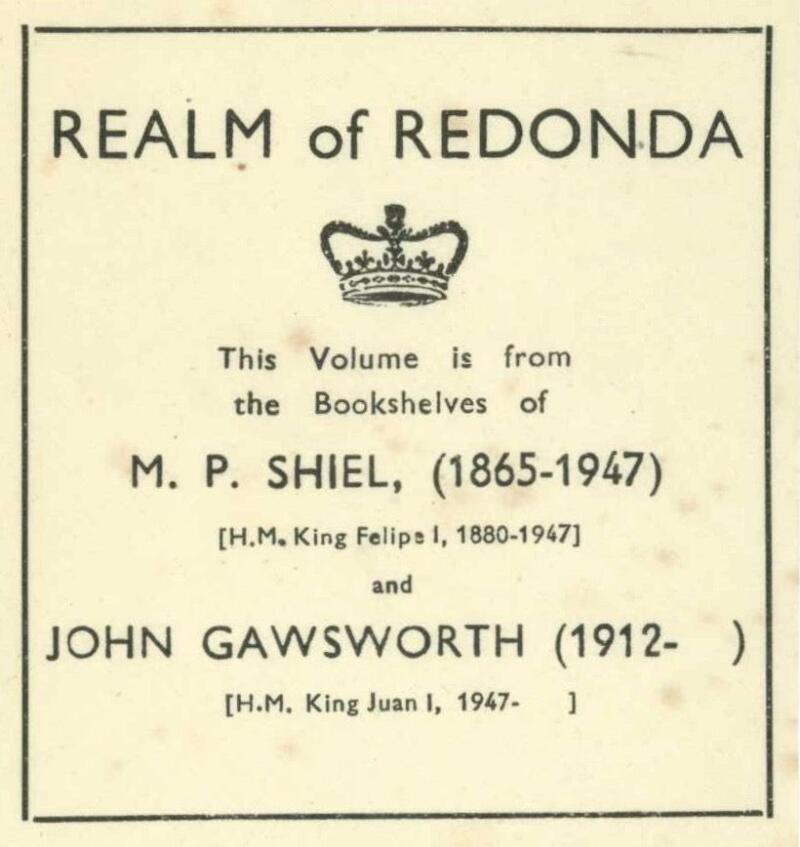

It seems that everything in this slightly fantastical history of Redonda hinges on whether or not Redonda is — or indeed: ever was — an independent kingdom, for without that status there would appear to be no Kingdom of Redonda, and hence: no succession of kings. And that foundational claim — the claim to independence — seems to rest upon an impulsive decision made by one Matthew Dowdy Shiell, at the time a Methodist lay preacher on the island of Monserrat, who allegedly laid claim to the entire island of Redonda in 1865, believing that no country had yet claimed it as their territory. The island was to be a gift from Shiell to his infant son, Matthew Phipps Shiell, born that same year; such is the uncontrollable pride (and perhaps the megalomania) of a new father, who cannot help but see his infant son as a future king. It is the younger Shiell (who eventually became a writer of pulp fiction in England of the 1920s, publishing under the byline of M. P. Shiel) who first tells the world of the Kingdom of Redonda, in recounting the story of his own coronation on Redonda in 1880 at age fifteen, crowned (he claims) by a bishop of Antigua, thus inheriting the throne from his father and taking the name King Felipe I of Redonda.

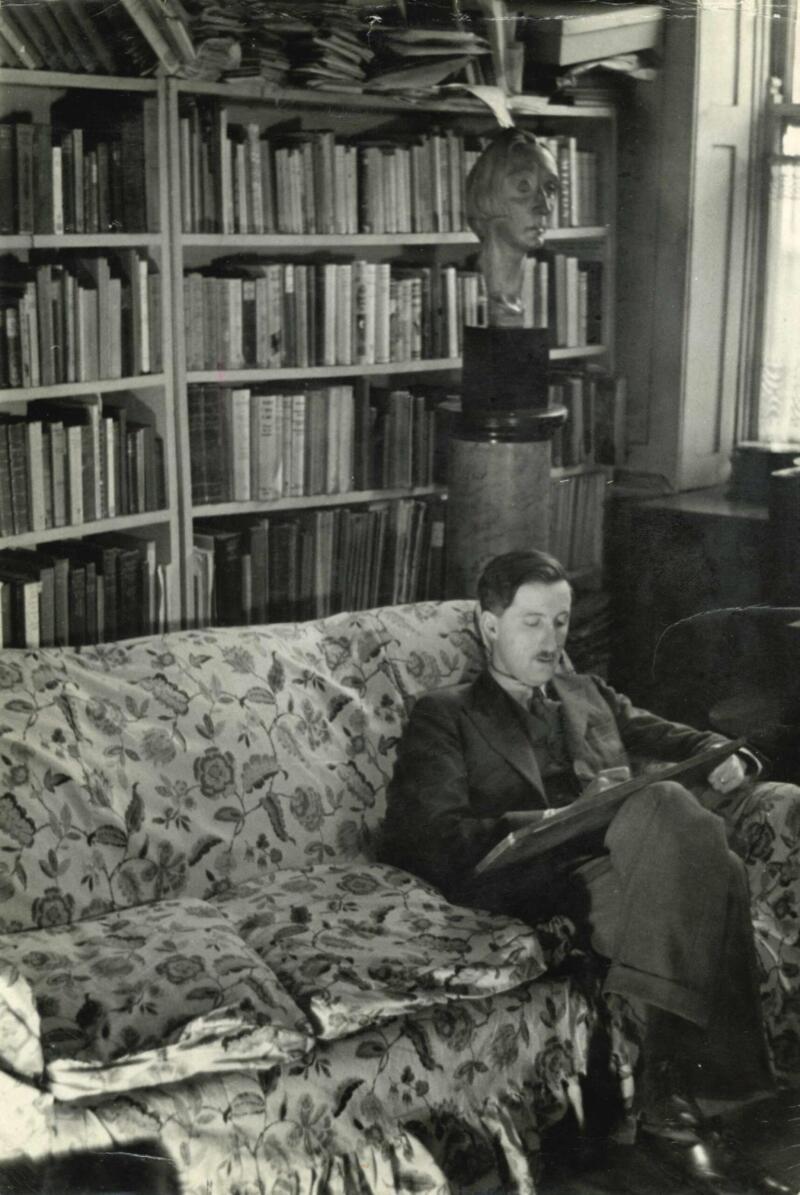

Stories of kingdoms and of kings have an appeal that is universal, and such tales retain their currency for generations. But as Hingston’s account reveals, kingdoms can also have another form of currency: the monetary kind, and one reason that the line of succession to the Kingdom of Redonda is now so knotted is that John Gawsworth, a minor poet, successor to King Felipe I and now known as King Juan I, is alleged to have exchanged his imaginary kingdom for a fistful of silver — to help pay off his very real debts. And he is further alleged to have done so — or attempted to do so — more than once (when the initial purchaser of the Kingdom learned that Gawsworth was attempting to sell it yet again, a lawsuit ensued.) This “sale” of the Kingdom, along with various other attempts to trade or gift the throne of Redonda to others over the years, have left a legacy of multiple competing claims to the throne, which Hingston methodically attempts to trace down and verify in his book.

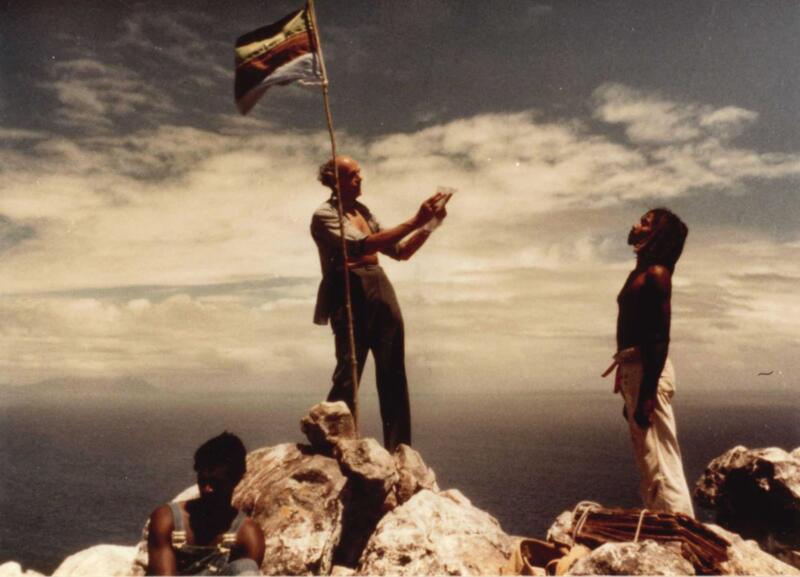

The most legitimate line of succession appears to be through Jon Wynne-Tyson, another relatively unknown British writer, who became King Juan II in 1970, having been formally bequeathed the throne by John Gawsworth — along with Gawsworth’s literary executorship. Wynne-Tyson appears to have embraced his role as king, even going so far as to visit his island realm in 1979 (there are photographs of this visit in Hingston’s book, showing Wynne-Tyson on the island’s summit, his open shirt and thinning hair whipped by a Caribbean wind). In 1997, Wynne-Tyson abdicated the throne, naming as his successor the Spanish writer Javier Marías, who took the name King Xavier I. Marías’s reign as king seems to have been the one which most honoured the fanciful spirit of the Kingdom of Redonda, since the Kingdom makes brief appearances in several of his novels. Tongues are firmly held in cheek throughout. As Wynne-Tyson puts it:

The legend [of the Kingdom of Redonda] is and should remain a pleasing and eccentric fairy tale; a piece of literary mythology to be taken with salt, romantic sighs, appropriate perplexity, some amusement, but without great seriousness. It is, after all, a fantasy.

What makes the reading of Hingston’s account of this imaginary Kingdom so pleasurable is the growing sense that all of the participants in the creation and perpetuation of this royalist fantasy were having so much fun! As Hingston puts it at one point, paraphrasing another of the many before him who have tried to unravel the tangled history of Redonda, “the Redondans were a loose assortment of merry men running around London in the 1940s and ’50s, throwing spirited parties, knighting their friends, and tossing off royal proclamations to an alternately confused and delighted press corps.” Anyone who is at all “bookish” (as Hingston so evidently is) will immediately feel a kinship.

As with most puzzles, literary or otherwise, there is an addictive aspect to the search for a solution, and Hingston’s account of his investigation into Redonda’s past also documents the stages of his increasingly impulsive quest, as he follows a trail of fading paper (book collectors will no doubt be familiar with this aspect of the tale). Many of the publications related to the Kingdom existed only as rare pamphlets or other forms of ephemera, often tucked away in far-flung university archives when they exist at all. As Hingston puts it: “parts of the story seemed lost entirely, printed on long-crumbled newspaper or taken to the grave by a series of unreliable men.” Still, despite these challenges, Hingston slowly builds up what he calls his “personal Redondan archive,” including “John Gawsworth’s personal copy of the original version of The Works of M.P. Shiel, […] the single most expensive book I’ve ever purchased.” When Hingston learns of an online auction at which Jon Wynne-Tyson’s entire literary archive is to be sold, he finds he can’t resist, and by auction’s end he is the slightly shell-shocked owner of not one, but two of the auction lots, containing material related to the Kingdom of Redonda (said material including — and the italics here are Hingston’s — “the actual flag [Wynne-Tyson had] planted on top of Redonda during his visit.” Reading this, you share his excitement, as well as the stunned realization that this spree has cost him “more money than I’d ever spent on anything that I couldn’t drive or live inside.”)

The final chapters of Try Not to Be Strange describe Hingston’s own expedition to Redonda: an opportunity to take his quest out of the archives and into the real world. Three different planes and a full day of travel take him from a wintery Edmonton to the island of Antigua. A further twenty-minute hop on an eight-passenger plane gets him to Monserrat. The last leg is aboard a sailboat skippered by yet another claimant to the Redondan throne (would-be kings appear to be legion!); it’s a great way to bring the tale to a close.

In a startling bit of coincidence, shortly after the publication of Try Not to Be Strange, the Kingdom of Redonda was once again thrust into the headlines when the Spanish writer Javier Marías passed away in September 2022 at age 70. The death of Redonda’s King Xavier I was more than slightly unfortunate timing (not least for Marías, who doubtless left many writing projects incomplete) since it prevented Hingston from including this latest development in his definitive history of the Kingdom.

I have not been able to determine whether Marías named a successor to the Kingdom in his will, or whether the Redondan throne remains vacant as of this writing. Which I suppose means that all those who feel that they have a legitimate claim to the throne should begin to gather their supporting documentation into manila folders. As the author of what must now be the authoritative history of the Kingdom of Redonda, Michael Hingston seems to me to be the person best qualified to rule on all competing claims, which is why I now nominate him to head the committee charged with selecting the Redonda’s next king. And if Hingston handles the task with alacrity and aplomb, I’d also suggest that a Redondan Dukedom would be entirely appropriate. The Strange Duke & Official Chronicler of Redonda, perhaps?

*

Michael Hayward is an avid cyclist and an inveterate reader, who is happiest when cycling along the backroads of France, with a good book in his pannier. Editor’s note: Michael Hayward has also reviewed a book by Theresa Kishkan for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1674 A literary kingdom”

Enjoy the articles!