1673 Hazel Wilson’s Haida robes

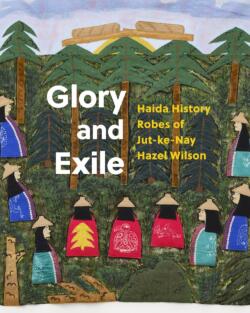

Glory and Exile: Haida History Robes of Jut-ke-Nay Hazel Wilson

by Robert Kardosh, Robin Laurence, Kūn Jaad Dana Simeon

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2022

$50.00 / 9781773271170

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

*

It is always fruitful to go on a journey with a quest and a good book about the destination. The book should tell a story about the place. More than a guidebook, a good book that can convey the essence of a place.

It is always fruitful to go on a journey with a quest and a good book about the destination. The book should tell a story about the place. More than a guidebook, a good book that can convey the essence of a place.

The quest obliges you to seek out, to learn, and to experience. The quintessential quest’s silver chalice is to return wiser.

The next time I go to Haida Gwaii, I will bring the book Glory and Exile: Haida History Robes of Jut-ke-Nay Hazel Wilson, and reread it there, in place.

It is an unusual book. It is about stories, Haida stories, as told to and by Jut-ke-Nay (meaning “The One They Speak Of”) Hazel Wilson, a Haida elder and artist, but she tells the stories through the robes, a series of fifty-one history robe textiles. These textiles are phenomenal and significant. Where else are stories told so explicitly through textiles?

I am reminded of J. Edward Chamberlin’s book If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories? In which he writes how stories give meaning to our lives. The title coming from a story of a Gitksan elder challenging foresters on exactly whose land they were on, eventually leading the way to the Delgamuukw case and the significance of Indigenous oral stories.

In Glory and Exile, Jut-ne-Kay tells her Haida stories through words and illustrated by button blankets. Yet, she has enhanced and expanded the art of button blankets with additional materials such as leather, shells, glitter and paint. These textiles have evolved from crests to history robes, each one illustrating a story.

Interestingly, in the English language, the word “textile” comes from the word for the texture of fabric, from the word to weave, the “text” or the “story” into the cloth.

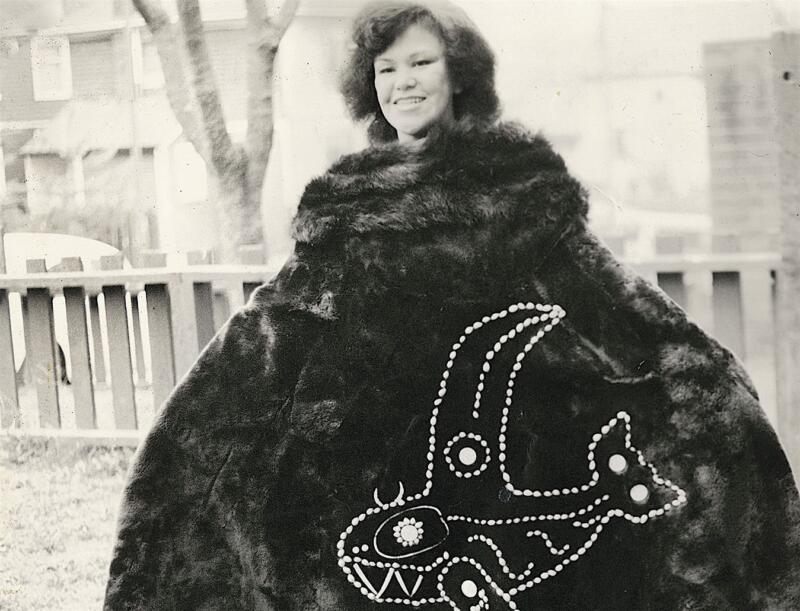

There is a scarcity of books featuring Indigenous textiles of the Northwest Coast, but a very relevant one from 1986, Robes of Power: Totem Poles on Cloth, includes Hazel (Jut-ke-Nay) Simeon’s (now Wilson) early work. In it (and in Glory and Exile) Jut-ke-Nay explains how a crest may show more than, for example, a killer whale fin. It can, in her case, be more specific: a crest with an extra high dorsal fin came from an uncle who was saved by the killer whale. He gave this crest to her grandmother, Mary Bell, who then added a circle and a dot. Her mother and she have the same pattern — a cat face on the tail — but Jut-ke-Nay added her own signature, a little mouth with teeth. When she wears it, her blanket tells people who she is and where she came from.

Also in Robes of Power, Dempsey Bob, who designed button blankets, tells us that, “In order to interpret the designs, you have to know the stories — family histories, yourself, people and nature.” When button blankets were very common, the designer, maker and even the reader understood the fine points.

Robes of Power starts with the suggestion that the visual narrative button blankets “[mark] the starting-point of a long journey of exploration of this art form,” and the book ends with the question, “who will take over where Robes of Power leaves off?”

That story may continue, but Jut-ne-Kay has certainly taken over and led the way since then. She has taken the narrative story form from button blankets to history robes. In 2005 she completed and exhibited seventeen robes that tell the origins, stories, and destruction of K’iid K’iyaas, the golden spruce. In a write-up of the K’iid K’iyaas exhibit, the Vancouver Sun heralded the work “as comparable in historical importance to the Bayeux Tapestry.”

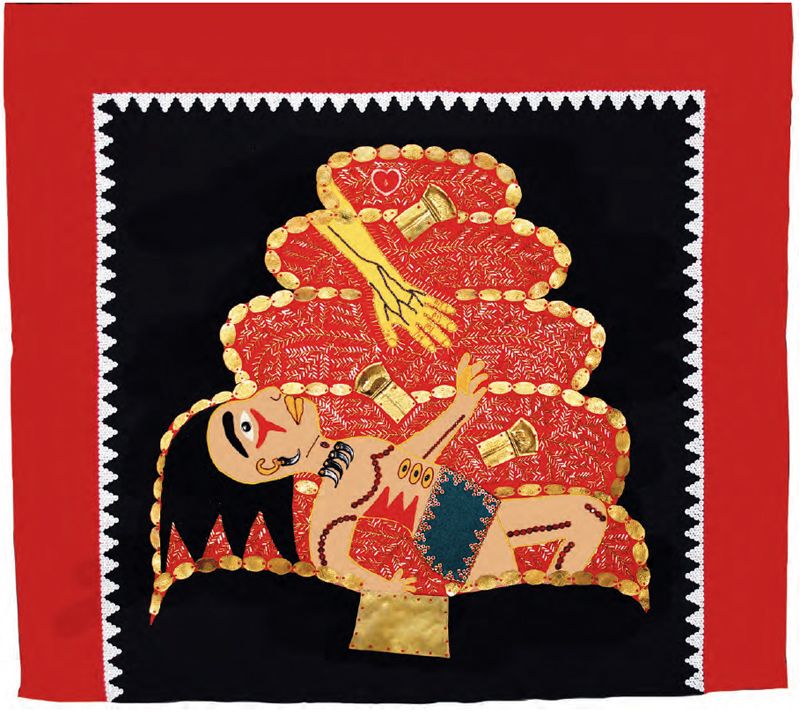

The Hand Reaches Out (2005). Mixed media on wool melton, 53.75 x 60 in. From the exhibit K’iid K’iyaas. “K’iid K’iyaas, fallen, is being raised up by the hand of the Creator, who will reunite him with his aunt, Hiilang Jaat. The heart with the tear-drop in the centre shows that he is remembered and mourned” — source of caption: Marion Scott Gallery. Courtesy Marion Scott Gallery and the Estate of Hazel Wilson. Rachel Topham Photography

Jut-ne-Kay took this concept one step further, and in 2007 completed her Haida History Robes which are all contained in this book along with their stories.

The book has six contributors and three sections. The first section consists of a foreword by Jisgang Nika Collison, Curator of the Haida Gwaii Museum, who places Jut-ke-Nay in her context as a resilient high ranking Haida clan woman, artist, and elder. Her daughter Kūn Jaad Dana Simeon provides a family perspective of watching her mother dedicate her life as a knowledge keeper by making button blankets.

Robin Laurence, a Vancouver-based art critic, provides a biography of Jut-ne-Kay’s life and artwork, from her destiny of being chosen by elders at the age of ten to become a button blanket artist, to her life as a blanket maker and to sudden acclaim in 2005 at the age of sixty-five for the Haida History Robes series.

Robert Kardosh, the Director of the Marion Scott Gallery in Vancouver, which has represented Jut-ke-Nay for decades and who was adopted into her family, provides an in-depth look at Jut-ke-Nay through historical context of Haida Gwaii and Jut-ke-Nay’s robes.

The largest section of the book concerns the stories and robes themselves. Each robe has a full-page illustration along with the story (often told in two versions). They are organized into three parts: “The Coming and Going of the Haida,” “The Mistake,” and “After the Storm.” Jisgang Nika Collison summarizes Jut-ke-Nay’s objectives:

To experience Hazel’s work is to learn a story within a story within a story: the past as taught by her elders; the life she herself experienced within these narratives; and a glimpse of our storied future, which we will build by upholding our own responsibilities to Haida Gwaii, the Supernatural, and each other.

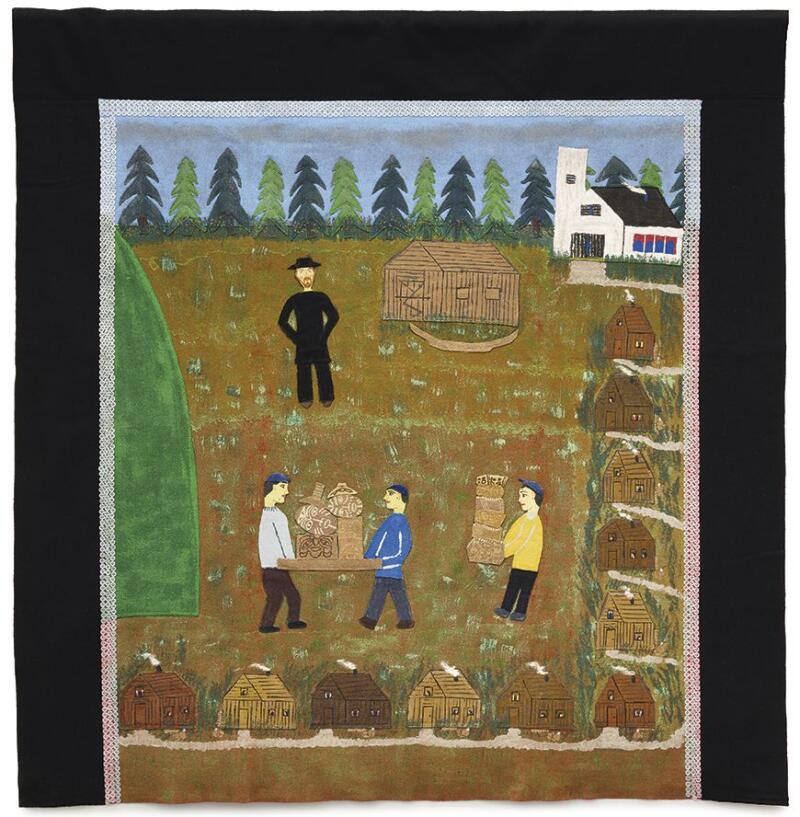

The robe Burial is a good example of that. It is framed on three sides with black melton cloth and three rows of buttons. Within that is a forest scene with three people looking in from the right, three from the left, and three with their backs to us. The background is mostly a forest with what looks like two burials on the treetops. Each person is wearing a robe with a crest. One, perhaps two, look like her family crest. Each crest was probably carefully chosen to match a deeper story. Jut-ke-Nay explains, “We put them up in the highest trees so that their souls are free to travel to Glory.” When the preachers came, they were not happy with that practice and ordered them to bury the bodies, explaining that their beliefs are why they were dying. She tells us that they will come back reincarnated, and they watch for them, like when her mother came to visit and Jut-ne-Kay’s eldest grandson came running out saying “Gracie Gracie [Jut-ne-Kay’s father always called her Gracie] you are still as beautiful as ever … Aljew [a name Jut-ne-Kay’s father gave her] is raising me now isn’t that great.” Only her father used those names, thereby proving to them that he was Jut-ne-Kay’s father — and her grandson.

When Jut-ne-Kay comes back, she says she will know more. “We plan on our next life to be better than as we are now.”

Through Jut-ne-Kay’s robes we also get a different perspective. Examples include how the preacher is viewed: “As children the preacher was a very frightening person he knew the devil.” And when the preacher told an elder to stop collecting down feathers, “Elder tells everyone not to [collect down] for no one should feel the way she did — it was elder they listened to, not the preacher.”

The stories embed history but also values — for example of respect, tolerance, non-interference with other beings, and working together. “We had harmony, we lived for each other….” The stories also dwell on how these values collided in recent history, for example when Jut-ne-Kay’s people were ordered to stop the happiness of sharing.

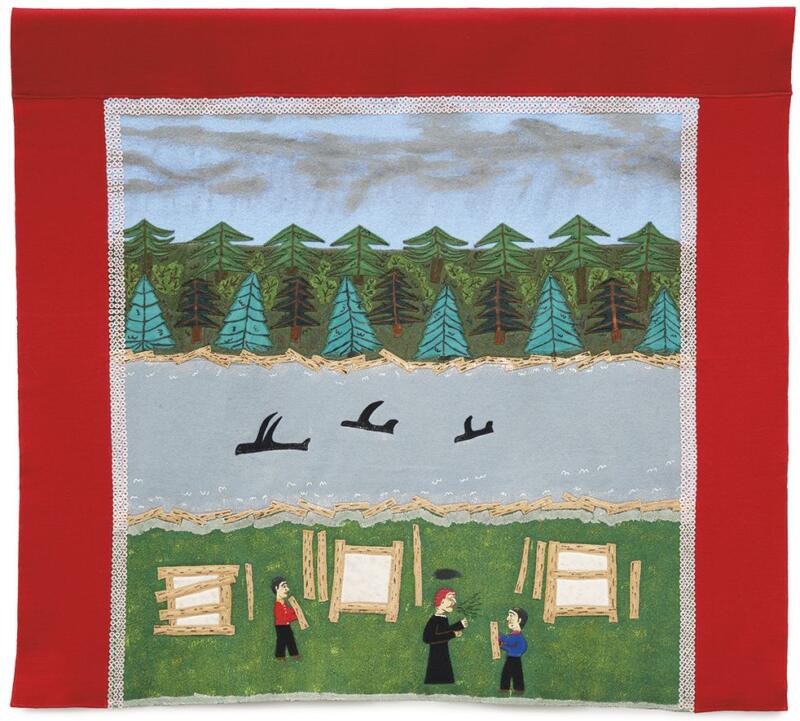

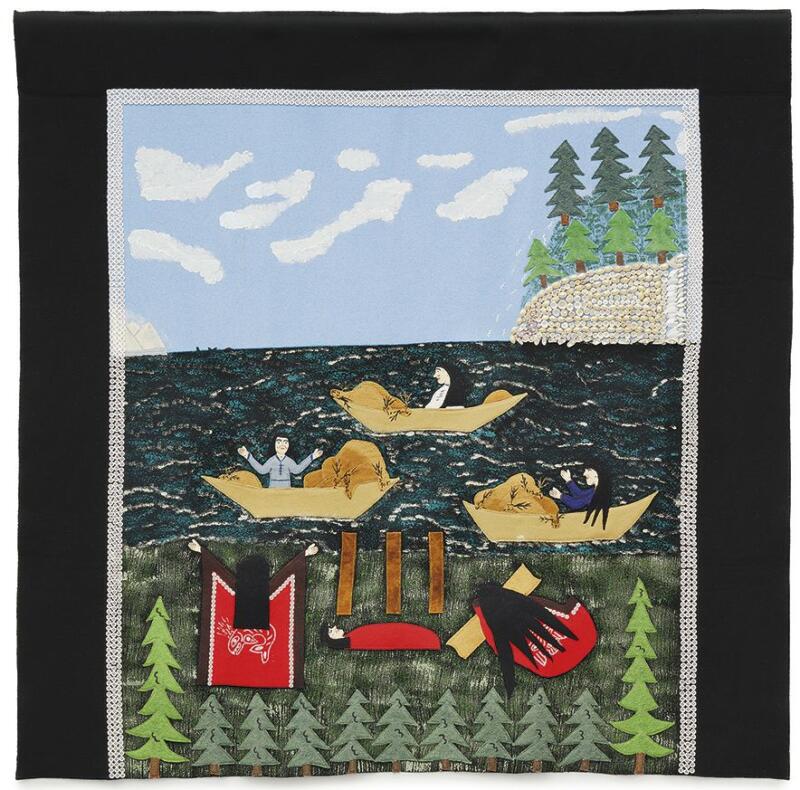

Another robe, Warning the Hunters Away, tells the story of three hunters on three canoes returning from a successful hunt only to find three posts, a warning sign to stay away. A “dark sickness” had struck the village. The story is told twice, a recounting of Jut-ne-Kay’s grandfather’s version and one from her uncle. It is the same story, yet different.

The Afterword, written by Chief Sgaann 7iw7waans, Alan Wilson, explains that Hazel and he tell the same stories but in different ways, and that Hazel “doesn’t simply tell her stories — she illustrates them. This makes them even more powerful.”

He talks not only about the importance of a story but of different meanings in the same story:

Each person grasps a different meaning — not different from what it tells, but a part that stands out to them… there’s a purpose behind every story — and it will have an effect, maybe unknown to the teller, but it will help someone, some way, somewhere, sometime. It’s pretty incredible when you think about it.

After reading Glory and Exile: Haida History Robes of Jut-ke-Nay Hazel Wilson I am impelled to make another journey to Haida Gwaii with a quest to visit the Haida Gwaii Museum and see some of Jut-ke-Nay’s work and to take the book and look at the landscape and see her stories.

*

Retired from Vancouver Island University where she held the position of Director of Research Services, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa now spends much of her time studying Coast Salish textiles. Along with a MA in Educational Technology, she holds a Master Spinners Certificate. She is a Research Associate with the Smithsonian and with VIU. She has worked with various museums including: the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the RBCM, MoA and the Burke Museum in Seattle in helping to identify yarns, fibres, tools and techniques used to create the yarns. She was instrumental in identifying a rare blanket in the Burke Museum confirmed to be made of woolly dog hair. She has given many presentations and workshops on the subject of Coast Salish spinning and textiles to Coast Salish spinners and weavers and has written articles on the subject for magazines such as Selvedge, Spin-Off, and Ply — and for BC Studies about the use of diatomaceous earth in Coast Salish blankets. She lives on Protection Island, BC, in Snuneymuxw territory. Editor’s note: Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa has also reviewed books by Aldona Jonaitis, Dempsey Bob, Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse & Aldona Jonaitis, and Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, & Willard Joseph for The British Columbia Review, and she has has contributed a tribute to Bill Holm.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1673 Hazel Wilson’s Haida robes”