1597 Get lost, young man

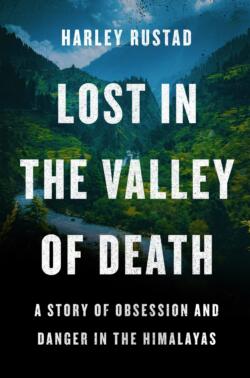

Lost in the Valley of Death: A Story of Obsession and Danger in the Himalayas

by Harley Rustad

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (Knopf Canada), 2022

$34.00 / 9780735279469

Reviewed by Daniel Gawthrop

*

For some readers, stories like this one are a tempting invitation to satire. There is, after all, much fodder for lampoonery in the cautionary tale of an earnest, young, able-bodied, white middle-class Western male who decides to opt out of the very society that has produced and enabled him. You know the kind: a young man born to privilege, marked for success, and stoked by his own sense of agency and entitlement, who decides to embark on a solo, material-free life of wilderness survival and ascetic discipline as the route to higher wisdom — and does so knowing full well that his high-risk adventures might one day end up killing him.

For some readers, stories like this one are a tempting invitation to satire. There is, after all, much fodder for lampoonery in the cautionary tale of an earnest, young, able-bodied, white middle-class Western male who decides to opt out of the very society that has produced and enabled him. You know the kind: a young man born to privilege, marked for success, and stoked by his own sense of agency and entitlement, who decides to embark on a solo, material-free life of wilderness survival and ascetic discipline as the route to higher wisdom — and does so knowing full well that his high-risk adventures might one day end up killing him.

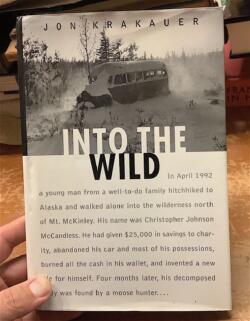

Of course, many more readers are happy to take this kind of story at face value. There is still much romance in the promise of transcendentalism, the notion that people and the natural world are inherently good, and that we only discover our true selves as human beings while in nature’s full embrace. Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild (1996), the story of American backpacker Christopher McCandless’s ill-fated odyssey as an off-the-grid, truth-seeking vagabond, began as an article in Outside magazine. But thanks to the Hollywood treatment, courtesy of Sean Penn’s beguiling 2007 film, the book is now available in 30 languages and routinely appears in high school and college reading curricula. It has spawned several more books and documentaries, most concerned with the question of motivation: why do gifted young men like McCandless — fed up with the soulless competition and empty rewards of capitalism, inspired by the likes of Thoreau, Twain, and Jack London — reject the modern world, even leaving behind their loved ones to follow a principled, if solipsistic, path toward authenticity?

The story that Salt Spring Island native Harley Rustad tells in Lost in the Valley of Death (a book that also began as an Outside article), has many parallels with Into the Wild. The narrative includes several references by both author and subject, whose story ended twenty-four years after McCandless’s. Like the former, Justin Alexander Shetler is highly intelligent, well-educated, and an avid reader. He’s also attractive and popular, expected to go far in life, and is idealistic, too (like McCandless, who donated the $24,000 remaining in his college fund to Oxfam, Shetler drains his savings to help the less fortunate, devoting his money to earthquake relief in Nepal, among other causes). Like McCandless, Shetler is disillusioned with the rat race, determined to challenge himself by living off the land, and willing to go as far as possible from his comfort zone to test his limits. McCandless adopted the pseudonym Alexander Supertramp; Shetler drops his surname and adds “Supertramp” to Justin Alexander. Like his hero, Shetler is also equally meticulous in documenting his adventures with photos and writing. Lost in the Valley of Death implies that the two men shared something else in common: they were both running away from childhood traumas.

*

In the wake of Krakauer’s worldwide bestseller, Rustad’s burden as a writer was to produce a story every bit as riveting as Into the Wild but with its own unique problematics. He certainly found his subject in Shetler, an enigmatic figure far more complex and sophisticated than McCandless. The former was a California suburbanite with a sister and several half siblings, the son of conservative parents who worked for NASA and Hughes Aircraft. The McCandlesses moved once, to Virginia, when Chris was young, and his vagabond life was a form of rebellion against parents who expected him to pursue a proper career. Shetler, by contrast, was the only child of parents who divorced when he was very young, his father becoming a hippie before abandoning his drug habit in favour of aikido, yoga, and vegetarianism. The boy lived with his mother and moved several times during his childhood. Unlike Chris, Justin faced no parental pressure: on the contrary, his folks encouraged his wanderlust, urging him — in the parlance of New Age philosopher Joseph Campbell — to take the hero’s journey and discover his bliss.

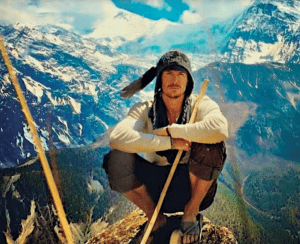

McCandless was a good athlete in school but knew little about wilderness survival when he embarked on his cross-country vision quest at age twenty-two. It’s anyone’s guess what paths he might have followed had he survived Alaska, but his horizon for adventure while he lived was confined to the continental United States. As Rustad reveals, Shetler was a trained expert in wilderness survival from an early age, a respected outdoorsman whose guiding skills were widely sought. And he was cosmopolitan, having travelled much of the world before landing in India at age thirty-five. A true Renaissance Man, he gained access to Indigenous and non-Western cultures without causing offence, mastered musical instruments as well as languages and cuisine, and began his final pilgrimage to enlightenment only after test running a few careers, including as front man for a popular punk band and as globetrotting entrepreneur for a tech start-up. Picking up where the pre-Internet McCandless left off, he built himself a massive social media following thanks to some slick videos and catchy philosophical musings (“Be kind and do epic shit.”).

Rustad, seeing what a media-savvy subject he had in Shetler, can’t resist noting the occasion when the young traveller was introduced in an L.A. bar to Jonathan Goldsmith, the suave, white-bearded American actor best known for his Dos Equis beer ad appearances as The Most Interesting Man in the World. Goldsmith, charmed by his new young friend and impressed by his many adventures — including becoming a monk in Thailand, rescuing a young girl in Nepal, and surviving 14 ayahuasca ceremonies in Brazil — tells him: “I think you might actually be the most interesting man in the world.”

Rustad, seeing what a media-savvy subject he had in Shetler, can’t resist noting the occasion when the young traveller was introduced in an L.A. bar to Jonathan Goldsmith, the suave, white-bearded American actor best known for his Dos Equis beer ad appearances as The Most Interesting Man in the World. Goldsmith, charmed by his new young friend and impressed by his many adventures — including becoming a monk in Thailand, rescuing a young girl in Nepal, and surviving 14 ayahuasca ceremonies in Brazil — tells him: “I think you might actually be the most interesting man in the world.”

*

I began reading Lost in the Valley of Death fully expecting to find Shetler completely insufferable: pretentiously progressive, self-righteous, and blindly hypocritical. But Rustad’s nuanced portrait makes it impossible to maintain such an impression. Over the course of the book, his subject emerges as a sympathetic figure who was generous, inclusive, self-critical, and clearly suffering from a life-long struggle with past demons (revealed in the book’s second half) that goes some way to explain his insatiable thirst for a life of complete integrity. Far from simply envying his many talents and achievements, you find yourself rooting for the guy. Given another of his qualities — an unwavering trust in the goodness of other human beings, despite incidents of having been cheated, robbed, or beaten up — the book’s inevitable ending becomes all the more heartbreaking.

Rustad recounts most of Shetler’s life story in the first forty pages before that pivotal moment when he “retires” at age thirty-two, quitting his well-paying job and hitting the road on a Royal Ensign motorbike, sharing his adventures on a hugely-subscribed Instagram account. For the rest of the book’s 270 pages, we are taken deeper into his psychological and spiritual journey over the next three years, a quest for self-knowledge that ends in 2016 with the exhausting sojourn in India that finally swallows him up.

Apart from its flawed protagonist, the real star of this book is the Parvati Valley, a remote and rugged corner of India known as much for its mystical traditions as for its infamy as a kind of Bermuda Triangle of the Himalayas. This is a dark and often dangerous place where, as Rustad reminds us with several examples, many a Westerner has disappeared without a trace. The Valley of Death comes to life in vivid detail as the author charts the geographical beauty of its mountainous landscape — an unforgiving terrain of perilous cliffs and violently churning rivers — while revealing its history as a magnet for truth seekers from around the world.

Setting up Shetler’s final trek into the unknown, Rustad recalls his own first visit to India in 2008 and how he covered some of the same tracks on the Hippie Trail that Justin’s father had during the 1970s and his own father had in the 60s: a legendary overland route from Istanbul to Delhi that, for many, has included a pilgrimage to the Beatles’ famous retreat on the banks of the Ganges in Rishikesh, where the Fab Four wrote much of the material for the White Album. The region, he notes, has become a popular place for disaffected Westerners to reinvent themselves:

Some of the travellers went to see the world, some went for the cheap hash, but others crossed the world for sincere, purposeful reasons: they fundamentally believed that India would open their eyes, fill in a spiritual blank space in their lives. The Hippie Trail was marketed as not just an exploration of the world but a probe of its spiritual facets along a pilgrimage to the birthplaces of Hinduism and Buddhism, a chance to walk the land of reincarnated monks and wandering sadhus and connect with the teachings and the symbolism — anti-materialism and minimalism, yoga, and meditation — of Shiva, Vishnu, and the Buddha.

Rustad, drawing from historical examples and a vast range of literature, provides much context for how Shetler became just another of the many nomadic truth seekers drawn to the Parvati Valley. He is especially good expounding on India Syndrome, the South Asian version of going native. “The condition has cousins around the world,” notes Rustad. “Religious tourists to Jerusalem are struck with a spontaneous psychosis upon visiting the city, certain that they are hearing God or in the presence of saints; visitors to Florence are physically overcome, even hallucinate, upon viewing the beauty of the city’s art.”

Shetler’s friends had noticed warning signs of his increasing alienation even before the trip to India, and Rustad notes how they cautioned him not to end up like McCandless. But few who knew this accomplished outdoorsman suspected that India would prove his undoing. After spending weeks in solitude, living in a small cave in the mountains, Shetler sought wisdom from a sadhu named Satnarayan Rawat. His final outing, just before his disappearance, was a long trek to Mantalai Lake, a place of astonishing beauty and peacefulness, with Rawat and a porter.

Rustad’s portrayal of Rawat, who many locals regard not as a real holy man but as an opportunistic charlatan just out for some cheap hash and a quick buck, raises the possibility of skulduggery in Shetler’s disappearance and possibly his death. The book’s final section recounts the efforts to locate Shetler and investigate his puzzling disappearance. Here Rustad’s work is reminiscent of another Krakauer bestseller. Into Thin Air provided a damning critique of mountaineering companies that make a fortune by bringing inexperienced climbers up Mount Everest; Lost in the Valley of Death raises ethical issues around the microeconomy of search and rescue missions, especially their distasteful competition for bereaving families. Some firms charge outrageously high fees to conduct searches for missing travellers — regardless of the low success rate and without always proving to the families what work they’ve done.

*

Into the Wild closed with McCandless’s tragic moment of clarity about the human connection his Alaskan adventure had sadly lacked. Starving and emaciated, stranded inside his abandoned bus, he scribbles it into a book later found beside his dead body: “Happiness only real when shared.” As Rustad reveals, Justin Alexander Shetler understood this principle all too well. His problem was finding happiness in the complete silence of his own company.

Lost in the Valley of Death is pretty “epic shit” in its own right: a poignant meditation on the conflict between solitude and connection, between the instant gratification of material life and “influencer” status versus the wisdom gained through hardship and trials. The book, which came out earlier this year, is likely not a favourite of the Indian government. For everyone else, it is highly recommended.

*

Daniel Gawthrop is the author of five non-fiction books including The Trial of Pope Benedict: Joseph Ratzinger and the Vatican’s Assault on Reason, Compassion, and Human Dignity (2013), and The Rice Queen Diaries (2005), both published by Arsenal Pulp Press. His first novel, Double Karma, will be published in Spring 2023 by Cormorant Books. Editor’s note: Daniel Gawthrop has also reviewed books by Karen Moe, Keith Maillard, Hassan Al Kontar, and Cheryl A. MacDonald & Jonathon R.J. Edwards for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1597 Get lost, young man”