1659 Into the hoard of life

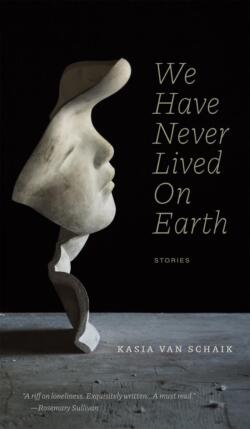

We Have Never Lived On Earth

by Kasia Van Schaik

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2022 (Robert Kroetsch Series)

$24.99 / 9781772126280

Reviewed by Carol Matthews

*

In response to a CBC question about the inspiration for her short story “An Ounce of Care,” which was shortlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize in 2017, Kasia Van Schaik said, “I’ve been thinking about what it means to care and be cared for in our era of climate change. Specifically, what it means to bring new life into a world in crisis.” This question is one that many young people are asking these days, and the short-listed story is now the concluding chapter of We Have Never Lived on Earth, Van Schaik’s new collection of linked short stories.

In response to a CBC question about the inspiration for her short story “An Ounce of Care,” which was shortlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize in 2017, Kasia Van Schaik said, “I’ve been thinking about what it means to care and be cared for in our era of climate change. Specifically, what it means to bring new life into a world in crisis.” This question is one that many young people are asking these days, and the short-listed story is now the concluding chapter of We Have Never Lived on Earth, Van Schaik’s new collection of linked short stories.

We Have Never Lived On Earth explores the care that exists between mothers and daughters, and between friends and lovers. It also considers what it means to care for other species — land animals, birds and whales — and, above all, for the planet. Van Schaik follows the travels of Charlotte Ferrier, a young girl who, with her mother and sister Nina, has immigrated to Canada from South Africa in 1990 after her parents separated. The stories carry us through Vancouver, Berlin, Montreal, Mexico, Amsterdam and Crete. The book might be classified as a bildungsroman, the novel of youth and development, but instead it is an intermingling of personal narrative, fiction, non-fiction and memoir that leaves the reader with more questions than answers.

The first chapter introduces Charlotte as a seventeen-year-old girl working as a cleaner for the Salloways, a pair of wealthy cognitive psychologists who are the parents of two of her schoolmates: a girl, Miranda, who never speaks to Charlotte and a boy, Charlie, who practices speaking words like extraneous, pugnacious, abhorrent as part of “a program designed for people who want to expand their vocabulary without having to read.” Charlotte’s work involves clearing out the untouched food in the fridge and feeling like a scientist “hired for the purpose of divining how such an environment might create a new life form, one that would remain after the world dried up.” This is what is happening to the earth, she observes. In a basket above the fridge are four-month-old half-eaten jellied pâtés that were

not jellies but whole wobbling armies of maggots, pearling in the cold light … a wriggling mass, their bodies inseparable from each other, from their occupation, their conditions of life.

Grace Salloway is an expert on childhood happiness and explains that “despite its name, happiness is not something that happens,” but something that needs to be cultivated. “How will you prepare for happiness?” she asks Charlotte, a question that Charlotte repeats to herself.

Charlotte moves through school days in which boys keep a Premium Girl List and the girls play a hating game. Summers are idle because the girls are the wrong age for anything: “We couldn’t legally work. Or drive. Attaining a tan was our sole ambition in June and maintaining it our only responsibility.” The pursuit of fun was “like the migration of Monarch butterflies.” How did the monarchs know where to go? Charlotte wonders. How did they know when they arrived?

The stories are told in the first person from Charlotte’s point of view, except for “Highwayman,” which is in the third person from the perspective of Paul, Charlotte’s father. In his backstory we see some of the trauma of the marriage breakdown and the awkwardness and futility of Paul’s attempts to connect with his children and their education. Paul is confused and unhappy about all the changes in his life: the wife having changed her name from Judy to Willo, his austere flat which is also his office, and his sense that the lights of his city are disappearing. Driving back after a disappointing afternoon with his wife at the beach, he falls asleep at the wheel, collides with a van and is given a ride by an Xhosa man and his son, while on the radio there is talk of electrical storms, lost airplanes and distant battlefields.

The news is never good. In “A Girl Called Helsinki” Charlie Salloway reappears, taller than before and changed by grief. He lets Charlotte read a letter that tells of Miranda’s death, written by a man named Elia who had befriended Miranda and let her stay with him. In his letter to Charlie, Elia tells of Miranda’s weeping and her obsession with the news:

An earthquake in a southern capital. A dismantled train. A spread of tuberculosis in India. A man had carried the body of his wife for seven miles. He had no car, the subtitles explained. The hospital would not provide him with an ambulance.

Elia believes that Miranda was enchanted by disaster stories, not by the disasters themselves but by the fact that they were distant and had no bearing on her life. But disaster is always close at hand. Miranda is abused by a boyfriend, moves to Warsaw and then Vienna, and dies in a collision in which she is thrown off a motorbike. Charlotte wonders if Elia would answer if she wrote to him:

What happened to an unlived life — this is what I wanted to ask him. Does it just unglue itself from the body, disappear? Or does it continue on, walking beside us, like the shadow trailing along the pier.

There is a sense of homelessness throughout this book. People come and go, always searching, always moving on in search of new environments, new relationships, new possibilities. In “Notes on a Separation,” Charlotte’s lover asks “Why didn’t you warn me? The reply from a clock: Time has run out. Time has run out. But later, Charlotte thinks, “There was nothing left to say except that life was moving forward in small, treacherous steps, steps that led to no particular direction, only forward, relentlessly forward.”

Charlotte’s travels seem aimless but, despite all the loss and disappointment, ultimately there is a sense of arrival. She is back with her mother and sister, the triangular family of women with whom she arrived in Canada. The question about whether or not to have a child remains unanswered, but Nina, herself a mother now, has orchestrated a reunion between Charlotte and her mother, Willo. “She’s our mother,” Nina points out. “She doesn’t have to be your friend.”

We Have Never Lived On Earth is a captivating, poignant, and often humorous account of childhood, adolescence and adulthood in a time of climate crisis. Van Schaik combines a precise yet lyrical voice that relates experiences, memories, dreams and hallucinations with keen observation and exquisite description in order to portray the world we inhabit these days: a complex, changing and challenging one that offers no easy answers.

The epigraph at the start of the story is by Virginia Woolf: Life is beginning. I now break into my hoard of life. In this book, we feel that we’ve been hurtled into the hoard of life of a young woman growing up in a time of racism, sexism, violence against women and immigrants, environmental degradation, rootlessness, and a disappearing future. Yet what mostly remains with the reader is the sense of beauty, longing and hope.

Van Schaik is an award-winning African-Canadian writer who has published short stories and poetry in a variety of places. A postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University, she is currently working on a book of cultural criticism entitled Women Among Monuments. I look forward to reading it — and anything else Van Schaik decides to write.

*

Carol Matthews has worked as a social worker, as Executive Director of Nanaimo Family Life, and as instructor and Dean of Human Services and Community Education at Malaspina University-College, now Vancouver Island University (VIU). She has published a collection of short stories (Incidental Music, from Oolichan Books) and four works of non-fiction. Her short stories and reviews have appeared in literary journals such as Room, The New Quarterly, Grain, Prism, Malahat Review, and Event. Editor’s note: Carol Matthews has recently reviewed books by Kristjana Gunnars, David Essig, Diane Schoemperlen, Susan Juby, Charles Demers, and Susan Sanford Blades for The British Columbia Review. Carol Matthews’ book Minerva’s Owl is reviewed here by Valerie Green

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1659 Into the hoard of life”