1596 A many-coloured coat

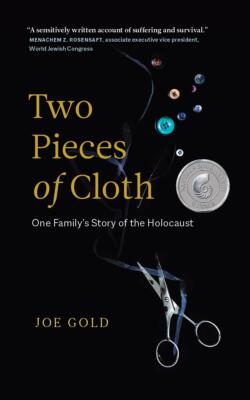

Two Pieces of Cloth: One Family’s Story of the Holocaust

by Joe Gold

Vancouver: Page Two Books, 2021

$21.95 / 9781989603826

Reviewed by Peter Hay

*

The vast literature of the Holocaust occupies various and distinct chambers in our latter-day imagination. First there are the historical documents which recorded or later reconstructed the names and vital statistics of millions of victims with lists of the places where they were tormented and perished. These factual records have been mined and moulded into narratives by scholars, museum curators and teachers of Holocaust history.

The vast literature of the Holocaust occupies various and distinct chambers in our latter-day imagination. First there are the historical documents which recorded or later reconstructed the names and vital statistics of millions of victims with lists of the places where they were tormented and perished. These factual records have been mined and moulded into narratives by scholars, museum curators and teachers of Holocaust history.

Then there are the personal memoirs and testimonies of the relatively few survivors which they handed down to their families, recorded in books, on film or in other media. These also form part of the historical record and provide material to establish details of everyday life and suffering that are missing in the endless lists of names and places.

Some of the testimonies were written by psychologists, like Victor Frankl and Edith Eger, whose professional insights shed light on the dark corners of the human psyche, as they sought to understand how and why they survived the atrocities that destroyed millions around them.

And then there is literature itself: a small but precious body of writings by survivors who tell us how it felt to be caught up in this most diabolical web of human history. The now classic works by Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, Imre Kertesz and a few others reflect not just on the factual reality that historians cannot fully convey, nor just the everyday miseries and survival strategies in the personal testimonies. Great writers transmute what they themselves experienced into universal narratives that continue to disturb our nights and haunt our imagination long after their authors have gone.

Joe Gold’s book, Two Pieces of Cloth, ambitiously attempts to combine these different strands. It is a factual record by the son of Holocaust survivors who tries to reconstruct his parents’ lives, based on family stories, letters and a long lost album, and he fills missing gaps with historical research. Mr Gold brings his family to life by having his parents speak as if they were alive, acting as semi-fictional characters in a play.

In alternating chapters, his father, David Goldberger, and mother, Aurelia Birnbaum (also known as Aranka), recount how they grew up in pre-war Czechoslovakia where their families prospered in the textile business. They met and married in June 1941, days before Hitler’s invasion of the neighbouring Soviet Union. Soon after, the right-wing government of Slovakia moved swiftly to “Aryanize” Jewish businesses by dispossessing the owners and giving their property to non-Jews. By the spring of 1942 the deportations to concentration camps in occupied Poland began. The young couple decided to flee from Bratislava to Budapest, in peacetime just a couple of hours’ journey by train.

Hungary was a German ally and seemed like a relatively safe place with a large Jewish population. But the country had a long history of anti-Semitism and introduced anti-Jewish legislation modelled on the Nuremberg laws starting in 1938. Refugees from Poland and other neighbouring countries under occupation were pouring in, until the Hungarian government closed its borders to Jews. It became necessary to obtain false papers and hire experienced guides to cross on foot to the other side. David spent a lot of time and what little money he could find to make the escape plan and then all the arrangements, while Aranka was already pregnant with their first son, Andrew.

After much suspense they made it to Budapest, where at least they knew the language. With help from former business connections, a few relatives and from total strangers they tried to re-establish themselves. It was not to last.

The Germans suddenly occupied Hungary in March 1944 when Hitler found out that the Horthy government was conducting secret negotiations for peace with the Allies. Even though the Germans were losing the war they redoubled their efforts to kill as many of the Jews they could round up in this last haven of refuge. Under Adolf Eichmann’s direction, more than 400,000 Jews were deported and murdered in Auschwitz within a space of three months.

David’s journey through hell began almost immediately. Because he was young and able-bodied, he survived as a slave labourer some of the most notorious death camps. By the time he was liberated less than a year later from Bergen-Belsen he weighed 65 pounds; later he would say that another two days in the camp would have finished him off.

Meanwhile Aranka went into hiding in Budapest with false papers. Little Andrew’s forged birth certificate showed him as a girl: the Germans and roaming bands of Hungarian fascists would stop mothers in the street to inspect whether their babies had been circumcised. With the Soviet army’s approach and the Allies’ bombing of Budapest, the civilian population was forced underground where they shivered through a bitterly cold winter while the city above them was reduced to rubble.

Miraculously, this tiny family of three managed to survive but they had not heard from each other in over a year. After liberation, David started on the long journey home. A walking skeleton, he encountered former inmates who were dying by the roadside. Everybody was hungry and begging for food or shelter. Some German farmers would help, others shut their doors. Organized assistance came only when David had made it to the bombed out city of Hanover where he even found a firm he used to do business with in pre-war days. Having listened to David’s recap of the past two years, the owners asked if they could give him some money. But with inflation raging, the Reichsmark was worthless. So David asked if they had any cloth he could use to barter with. They brought out two pieces of wool fabric they had kept hidden away.

David accepted the pieces of cloth and after further adventures found his way back to Aranka and Andrew in Budapest. Slowly recovering their health, the young couple set about to rebuild their life in Bratislava. Aranka could sew and David started to grow a wholesale business from the seeds of those symbolic pieces of cloth. Meanwhile the family grew in 1947 with the arrival of baby Joe, the author of this book.

But the following year, the Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia presented fresh dangers, so the Goldberger family left Europe behind and landed in Vancouver where Joe still lives, while his brother Andy emigrated to Israel.

The Gold family, with their new shortened name, left a rich legacy of philanthropy in their adopted land. Gold’s Fashion Fabrics became a block-long landmark at Granville and 11th Avenue, and both Aranka and David lived into their nineties.

David had always meant to record his experiences for his family, but never got around to it. His powerful narrative forms the backbone of this attractively produced book by his son, who uses his father’s voice — literally: David had provided testimony for the audiovisual project initiated by Dr Robert Krell in the 1980s, which recorded many eyewitness survivors. These are kept at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre which Dr Krell, himself a child survivor, also helped to found.

Two pieces of cloth, lives torn and stitched together again, and now printed on rags of paper, woven with photographs into a many-coloured coat.

*

Peter Hay was born in Budapest in 1944 and survived the Holocaust as a hidden baby. He landed in Canada in 1967, worked in theatre and publishing, and wrote nine books. He now lives in Summerland. Editor’s note: Peter Hay has also reviewed a book by Robert Krell for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1596 A many-coloured coat”