1589 The empty spaces of love

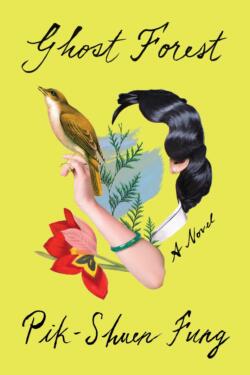

Ghost Forest

by Pik-Shuen Fung

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland and Stewart), 2021

$22.00 / 9780771096488

Reviewed by Michelle Ha

*

“How do you grieve, if your family doesn’t talk about feelings?”

“How do you grieve, if your family doesn’t talk about feelings?”

This is a question that I feel like many children of immigrants can relate to, and most may have asked themselves as well — as I know I have done many times before. How do you understand your own emotions if you have never been able to talk about your feelings?

In Ghost Forest, our nameless narrator considers this question after the death of her father when she revisits her memories of him. Having immigrated to Canada at a young age due to the Hong Kong handover in 1997, when the British returned sovereignty over Hong Kong to China, the narrator had grown up in the fresh air of Vancouver with her mother, little sister, and grandparents. Her father, though, stayed behind in Hong Kong to work and provide for the family and their new lives. This was common at the time for many Hong Kong immigrants, when families in the West were known as “astronaut families,” a term coined by Hong Kong media to describe “a family with an astronaut father — flying here, flying there” (p. 6).

Pik-Shuen Fung’s quiet debut novel is sparsely written with each page a new “chapter” that cleverly reflects the narrator’s memories in vignettes. While seemingly quiet and tender, Ghost Forest is equally witty and humorous. There were times when I resonated with the narrator’s experiences, especially in her interactions with her father and when learning the (hi)stories of her grandparents and their grandparents; but there were moments when I was emotionally impacted with the topics the book explores, and just as quickly my tears turned into abrupt laughter as Fung artfully and tastefully took an unexpected but refreshing turn in dialogue and scene.

Ghost Forest is a portrait painted in simple yet effective language on grief and guilt, on different forms of love, on family sacrifices and regret, on an immigrant story, and on forgiveness. It is a patchwork of an individual’s memories and family stories that speak for many diasporic experiences, as Pik-Shuen Fung represents the dichotomy of the West and the East through the relationship of a Western-raised narrator and a traditional Chinese father.

Born in Hong Kong, the narrator immigrates to Canada at the age of three. She experiences the cultural differences between East and West, specifically the cultural hurdles brought on by her upbringing in a Western society and her father’s values and mindset as a traditional Chinese man. And due to these differences, a sort of cultural rift is formed, a crevice in the narrator’s relationship with her father.

In most of her memories, the narrator and her father have a difficult time seeing eye-to-eye, most seriously in communicating and showing affection. The narrator might say “I love you” to her father, but he will never say “I love you” in return, instead musing that, “You’re getting a lot of western education…. We’re Chinese. It’s not important for us to express our feelings. Underneath this sky, all parents love their children” (p. 93). Or when the narrator, after talking to her father on the phone, faces his disappointment and anger in person for now knowing how properly address him properly, her own father, on the phone. The relationship between narrator and her father represents what many children of immigrant parents might relate to, myself included – a strain and barrier between first and second-generation immigrants due to differences in societies and upbringing. With sparse pages and simply written words, Fung manages to illustrate this complex relationship between immigrant parents and children in language both relatable and understandable.

Elsewhere novelist K-Ming Chang (author of Bestiary) has called Ghost Forest “an intimate act of recording and reckoning,” which “trusts us to listen [and] shows us all the languages for love.” Indeed Fung reveals the many ways that the three simple but powerful words “I love you” — an expression seldom used in most Asian households — can be expressed and said within the blank spaces of her novel. She explains that blank spaces are important in the art form of xieyi — xie being “to write” and yi an “idea or meaning,” that is, “to write meaning” — where the practice is meant to capture the artist’s spirit.

The empty spaces in Ghost Forest play an equally important role in understanding these unspoken but implicit “I love you’s,” and the narrator’s memories and interpretations of her interactions with her father and family capture Fung’s own artistic spirit in this beautifully written novel.

*

Michelle Ha is a second generation Chinese Canadian artist, writer, and editor. As much as she enjoys staring at a blank canvas or page every now and then, she also has other interests that include archery, photography, writing letters to pen pals, playing cosy games, and reading translated literature and “own voice” stories by marginalised writers. Much of her work in the literary and fine arts world, and in her personal life revolves around supporting and uplifting the voices of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour, along with folks of the LGBTQIA+ community. She currently works as a digital publisher for Geist Magazine and is an active editorial member for Room Magazine. Michelle graduated from the University of Victoria with a bachelor’s degree in English and a minor in Professional Journalism and Publishing. Editor’s note: Michelle Ha has also reviewed a book by Sarah Suk for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster