1559 Coming of age in Hogan’s Alley

Junie

by Chelene Knight

Toronto: Book*hug Press, 2022

$23.00 / 9781771667685

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

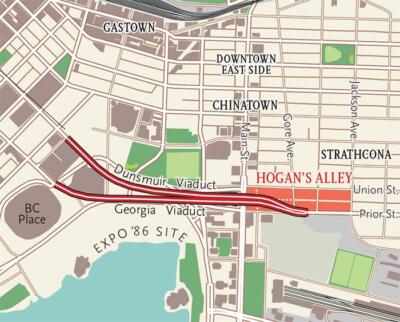

Strangers to Vancouver or its history before the city’s breakneck condo-ization might wonder about “the Village,” the comfortable place June-Anne Lancaster—the protagonist of Chelene Knight’s appealing first novel — affectionately sees as her hometown. In the vicinity of Main and Prior Streets, the Village is a pocket of what Junie and her neighbours call “the East End.” Like Halifax’s Africville, the Village no longer exists.

Strangers to Vancouver or its history before the city’s breakneck condo-ization might wonder about “the Village,” the comfortable place June-Anne Lancaster—the protagonist of Chelene Knight’s appealing first novel — affectionately sees as her hometown. In the vicinity of Main and Prior Streets, the Village is a pocket of what Junie and her neighbours call “the East End.” Like Halifax’s Africville, the Village no longer exists.

In 1933, when Junie opens, there was no DTES and its commonplace associations, particularly the lingering reputation as dangerous, the worst postal code in Canada. (Postal codes weren’t introduced until 1971, for one). Though the area’s predecessor, the East Side or East End, was defined in relation to affluent and Anglo areas west of Main, many residents of the working class neighbourhood would have prided themselves on a thriving community abuzz with political activism, nightly entertainment, and ethnic diversity.

In Knight’s portrait, hobbling poverty, widespread addiction, and crippling disenfranchisement remain largely out of sight. “This is home,” Junie exclaims, and the romantic adolescent often grows rhapsodic about shops, laneways, and passersby. She’s enthralled with the delights her immediate world can offer; she hopes to capture every hue, shadow, and nuance.

In the “Author’s Note” of Junie, Knight, a Harrison Hot Springs resident, refers to the Hogan’s Alley Society’s website. The Society describes Hogan’s Alley as the unofficial name for a small area of Strathcona, a “diverse immigrant enclave” and “home to Vancouver’s Black population” that was effectively destroyed with the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts in 1972. On a wet Sunday in January Tom Campbell, the mayor, was driven in a limousine to inaugurate Vancouver latest embrace of the future. (Turns out, the Viaducts will have an abbreviated history too; they’re planned for demolition within the decade.)

Although readers can view Knight’s novel through the city’s historical evolution, it’s largely beyond the novel’s scope. When Knight ends her tale, in 1939, war clouds the atmosphere, but concrete-pouring on Georgia Street is decades away. In that “Author’s Note,” Knight also mentions learning about the East End and Hogan’s Alley a decade ago and discovering that “there was not a lot of information out there” that preserved the neighbourhood and its people. She adds: “Hogan’s Alley was indeed a real place situated in the Strathcona neighbourhood, but all the cafés, diners, shops, and clubs described, however, were sparked from my imagination.” In writing, Knight aimed to create a world where readers “could fall into the daily lives” of Junie’s characters and “fall into the everydayness of their world without distraction.” Accordingly, Knight “chose to not focus on the destruction … and instead bring back a small moment in time where life was happening and flourishing, but not truly paid attention to.”

*

Fittingly for a coming of age story, Junie’s challenges and growth are Junie’s central concerns. Knight captures her as keenly observant and wonderfully conflicted. She aches with yearning, intuiting — if not yet able to name — places and roles where her adult self will be fulfilled. In brief yet poetic standalone segments that follow chapters written in third person, Junie parses the foregoing episode. Her voice captivates with hard-won knowledge and perception.

As a Black girl who has begun to question her sexual identity, Junie dreams of a life that’s beyond her experiences and distinct from what she’s known and seen. She draws and paints; she envisions art as a calling she must answer. And unlike other girls, Junie’s altogether uninterested in securing a husband and settling into domestic life.

When she becomes friends with Estelle, whose beauty draws Junie’s artist’s eye and heart, she’s a 13-year-old residing in a row house. New to the area (her mother having left Los Angeles during Prohibition) she’s poised to stretch her boundaries.

Like superficial, romance-hunting Estelle, Junie feels stymied not only by age but lack of agency. The girls comprehend the source of their clipped wings: their respective mothers. Burdened by responsibilities and dreams of respect, wealth, and celebrity, Faye and Maddie surface as colossal obstacles. Canadian literature has a long tradition of daughters negotiating for space with resolute mothers and, per tradition, for the duration of Knight’s novel Junie and Estelle struggle (and struggle again) to define themselves on their own terms.

“Estelle, don’t start now. Just remember, my mama ain’t like your mama,” Junie exclaims. “She’s a different kind of mama.” Indeed, abrasive, domineering, and exacting Estelle looms over her daughter. Her criticisms torment Junie; Junie’s clenched fists, a motif, seem inconsequential relative to her mother’s outsized personality and acid tongue. Maddie dreams of stardom and queenly entitlement. And she desperately bolsters a fatal self-regard (that’s a striking mythology of self too: “I own this damn town,” she scoffs, despite evidence and despite the fact that frequent inebriation and diva antics result in firings over and again). Maddie expects obedience from her daughter, whom she regards as an acolyte and servant whose primary purpose is to support her mother. And when Junie’s sexual identity dawns on her, Maddie replies with ire: “You ain’t right. You hear me. You. Ain’t. Right.”

Similarly, fiercely independent and committed to her night club, Faye, Estelle’s mother, has little spare time for her daughter and not much of an instinct for the mothering Estelle seeks.

By the novel’s final half, Junie has finished school and works as a diner waitress. When she and Estelle converse they learn how little circumstances have changed: their mothers, strong as ever, exert influences that are nearly impossible to resist.

Drawn boldly and yet subtly finished, Knight’s account of the fraught dynamics of these intimate relationships is a stand-out feature in an accomplished novel.

As a poet (Dear Current Occupant won the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2018), Knight showcases language that is artful in capturing mood, thought, and physical environment. With that said, her approach to characterization can err on the side of mechanistic.

Consider Shirley, Junie’s former teacher. “Times were changing and things were looking bleak. She felt even more compelled to help her students establish a solid foundation and strong work ethic. This desire had become urgent to Shirley.” A few chapters later, the narrator continues to list character motivation: “Shirley needed the accomplished feeling of keeping busy and supporting folks in the community… she felt a strong desire to nurture.” Aside from ignoring the ‘Show Don’t Tell’ commandment, the narration reduces the character’s complexity while underscoring her function in the story: Shirley is lessened as a character because she exists, in a sense, as a foil that serves a need for the development of the story’s protagonist.

As a portrait of “a small moment in time where life was happening and flourishing, but not truly paid attention to,” Junie serves capably in reconstructing lost history in the form of unknown people in a community scattered by municipal power years ago. In focussing on Junie’s family (and chosen family, eventually), Chelene Knight prioritizes the tremendous effects of intimate personal relationships. A city council might vote to remake a city in the name of progress or efficiency, but in Junie self-determination starts at home — in rooms a girl shares with her mother and on the streets where she stops at the local bookstore or bumps into a teacher whose acts of caring many years ago provided loving guidance that could last a lifetime.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, published in 2021 with Now or Never Publishing, is reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous book, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O (2018), was reviewed by Dustin Cole. Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has recently reviewed books by Lyndsie Bourgon, Gurjinder Basran, Don LePan, Paul Headrick, Christopher Evans, and Brad Fraser for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1559 Coming of age in Hogan’s Alley”