1558 Animal farms

Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade

by Rosemary-Claire Collard

Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2020

$24.95 (U.S.) / 9781478010920

Reviewed by Susan Nance

*

The traffic in wild and captive-bred exotic animals is estimated to be the world’s fourth largest illegal trade—after drugs, human trafficking, and counterfeit products — in 2020 valued at over $119 billion U.S. How can we expect any species to contend with that? Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade by geographer Rosemary-Claire Collard explores that question through an analysis of the exotic pet trade. This intelligent and sobering book is a welcome study of this crucial topic in animal and environmental studies. While recent film exposés of the wild animal show trade, like Blackfish and The Conservation Game, have raised public awareness of the origin and fate of wild and exotic animals today, the topic has received relatively little scholarly attention. Perhaps this neglect is owing to the logistical difficulties involved in finding sources or engaging in fieldwork regarding what Collard rightfully terms “this shadowy trade… [which] goes unremarked upon, under the radar of everyday people, media, governments, and academic study” (p. 3).

The traffic in wild and captive-bred exotic animals is estimated to be the world’s fourth largest illegal trade—after drugs, human trafficking, and counterfeit products — in 2020 valued at over $119 billion U.S. How can we expect any species to contend with that? Animal Traffic: Lively Capital in the Global Exotic Pet Trade by geographer Rosemary-Claire Collard explores that question through an analysis of the exotic pet trade. This intelligent and sobering book is a welcome study of this crucial topic in animal and environmental studies. While recent film exposés of the wild animal show trade, like Blackfish and The Conservation Game, have raised public awareness of the origin and fate of wild and exotic animals today, the topic has received relatively little scholarly attention. Perhaps this neglect is owing to the logistical difficulties involved in finding sources or engaging in fieldwork regarding what Collard rightfully terms “this shadowy trade… [which] goes unremarked upon, under the radar of everyday people, media, governments, and academic study” (p. 3).

To bring the stories of captive wild pets to light, Collard mines contemporary government and NGO studies of the trade as well as academic environmental studies literature that she uses to contextualize her own field research. Collard ventures out to a number of linked settings: biosphere reserves where wild animals and their habitats are under threat from illegal activity seeking to monetize them; the chilling world of arena and convention centre exotic animal auctions; and, finally, rehabilitation centres, or sanctuaries, in which animals removed from the trade are held before being released back into the countryside. These settings produce a network connecting jungles and other rural places in the developing world to backyards and basements, primarily in the United States.

The environmental backdrop of the story Collard tells is the accelerating “defaunation” of the planet wherein targeted animals including parrots, monkeys, and countless reptiles struggle to exercise autonomy in the era of globalization. Liberal property laws and constantly expanding transportation and trade networks have put many species in an increasingly precarious situation in the wild, vulnerable to capture and commodification on a scale unknown before the 1990s. The exotic pet trade is thus part of a larger process of turning the animal world upside down, Collard argues. Destruction of habitat, animal capture and confinement, population declines for many wild species, and exploding populations of domesticated animals (many of them hidden from us in CAFOs and other institutional settings likewise involving confinement and terrible welfare) expose the role of consumerism in all of it.

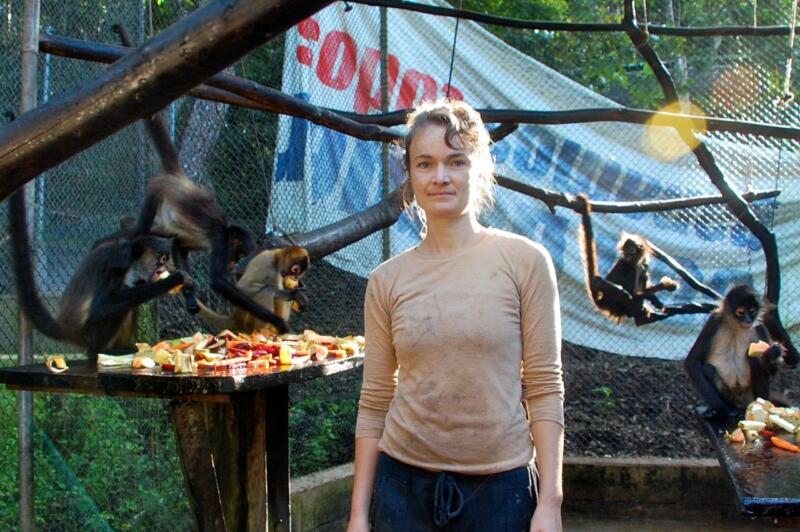

Many readers will find most compelling Collard’s vivid and honest descriptions of her fieldwork. For instance, she visits Reservas de la biosfera de México to speak with local biologists about the macaws and others whom they seek to protect from illegal capture and trade, and about the people who capture and trade wild animals. In rural Ohio, Collard attends rural midwestern animal auctions to hear exotic pet buyers and sellers talking about what they do and why, how they see exotic pets as a guaranteed “freedom” and a right. There, she explains how her presence threatens to disturb that which she seeks to measure as people give her funny looks and can tell she is an outsider to the community. At the ARCAS — Asociación de Rescate y Conservación de Vida Silvestre — sanctuary in Guatemala, Collard tells us about Stevie, a young spider monkey, and his confusion with the rehabilitation process. Once a household pet, Stevie is subject to “misanthropic practices” that staff use to untrain him to seek out humans: Don’t call the monkeys by their pet names; no eye contact; spray them with hoses to make sure their contact with people is frightening and uncomfortable. The brief volume also contains helpful illustrations including a number of thoughtful photographs by the author that bring home the ethical perspective of the book. For instance, the chapter explaining captive exotic birds is concluded with a photograph of migrating Canada geese flying in formation.

Academic readers will find the book theoretically sophisticated. Collard, a geographer at Simon Fraser University, examines the exotic pet as a living paradox. Her analysis is grounded in commodity fetish theory to describe how inanimate objects take on meanings and values that are greater than their utilitarian value. Exotic wild animals are living, free beings who are transformed into a commodity at the moment they are captured. Collard explains, “a pet is a sentient, dynamic, emotional being who is made thinglike when it is made a commodity, made property, through markets, the law, the state, and other institutions and mechanisms” (p. 5).

Exotic pet owners transform previously-free wild animals into pets, that is, household companions who can be both cared for and controlled, through a number of acts that disconnect those nonhumans from their previous lives, families, and habitats. Owners individualize once anonymous wild animals by giving them names and train them in behaviours specific to captivity. This process, she argues, “involves the cutting off of the animal from the complex history of its own being. It operates … by denying a life of its own to the animal, rendering it a passive ‘resource’ and covering over the intricate socio-ecological relationships that produce this life” (p. 24). Like many consumer products, the means of producing and transporting exotic animals to pet keepers is hidden from them, like the environmental costs which are obscured since so distant from the consumer. Importantly, Collard asks us to think about what these animals experience as individuals obligated to survive in settings that cause “extremely high mortality rates, as well as stress, trauma, and ill health” (p. 84) as people hold them captive simply because they can.

Animal Traffic is an important study since it examines the intersection of wild animal traffic and the consumer habit of petkeeping, two modern phenomena that are closely linked but seldom analyzed as such. Like all books about animals, this one is also about what it is to be not-animal, that is, human. Collard depicts us as a species that does incalculable damage to animals, both as populations and individuals, yet does not have the capacity to reverse course. The damage we cause is not simply ecological or environmental, contributing to extinctions and habitat destruction. Collard persuasively argues that in removing animals from their spaces, people steal “animals’ use values for each other… [as] kin, parents, … [someone] good at obtaining food for the community,” replacing it frequently with premature death, severe behavioural and psychological problems, and, undoubtedly for many, daily experiences of loneliness and joylessness (p. 84) To the beings whose independent lives and families are stripped away in the process of feeding a self-interested, ignorantly-anthropocentric consumer demand, the damage we cause is individual and we should see it in moral terms, Collard argues, pushing us to ask: Do wild animals have a right to their own lives?

*

Susan Nance is Professor of History and affiliated faculty with the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare at the University of Guelph, Ontario. An internationally recognized researcher in the history of animals and the business and management history of live entertainment, she is the author of various books about animal history, including Rodeo: An Animal History (2020) and Entertaining Elephants: Animal Agency and the Business of the American Circus (2013). She is currently working on a history of the exotic animal trade in 20th century America.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster