1553 All that flickered

Hollywood in the Klondike: Dawson City’s Great Film Find

by Michael Gates

Madeira Park, Harbour Publishing, 2022

$34.95 / 9781550179965

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

All that Flickered: The glitter of gold competed with the flicker of silent movies in 1890s Klondike

All that Flickered: The glitter of gold competed with the flicker of silent movies in 1890s Klondike

You can almost taste the rotgut liquor and smell the sweat, cheap cigars and perfume in this historical account of Dawson City’s heyday in the 1890s. You can almost hear the hoots and hoorays on the 4th of July down at the many saloons and hotels. And you can almost feel the utter loss of a claim gone bust or the heartbreak of a prospector who gave his stake to a dancehall girl.

Klondike takes us back to a time that we only know from books and movies. Think Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush or Mae West in Klondike Annie and many other less famous actors who never made it out of the silent era and are now forgotten. Well, not quite forgotten. Author Michael Gates, then Parks Canada’s curator of the Klondike National Historical Sites, discusses several of them and their movies.

The Klondike fostered dreams of getting rich overnight and fired imaginations that among other literary treasures gave us the wonderful poetry of Robert Service and the stories of Jack London, whose The Call of the Wild was made into a silent film in 1923. Both win cameo roles in the book.

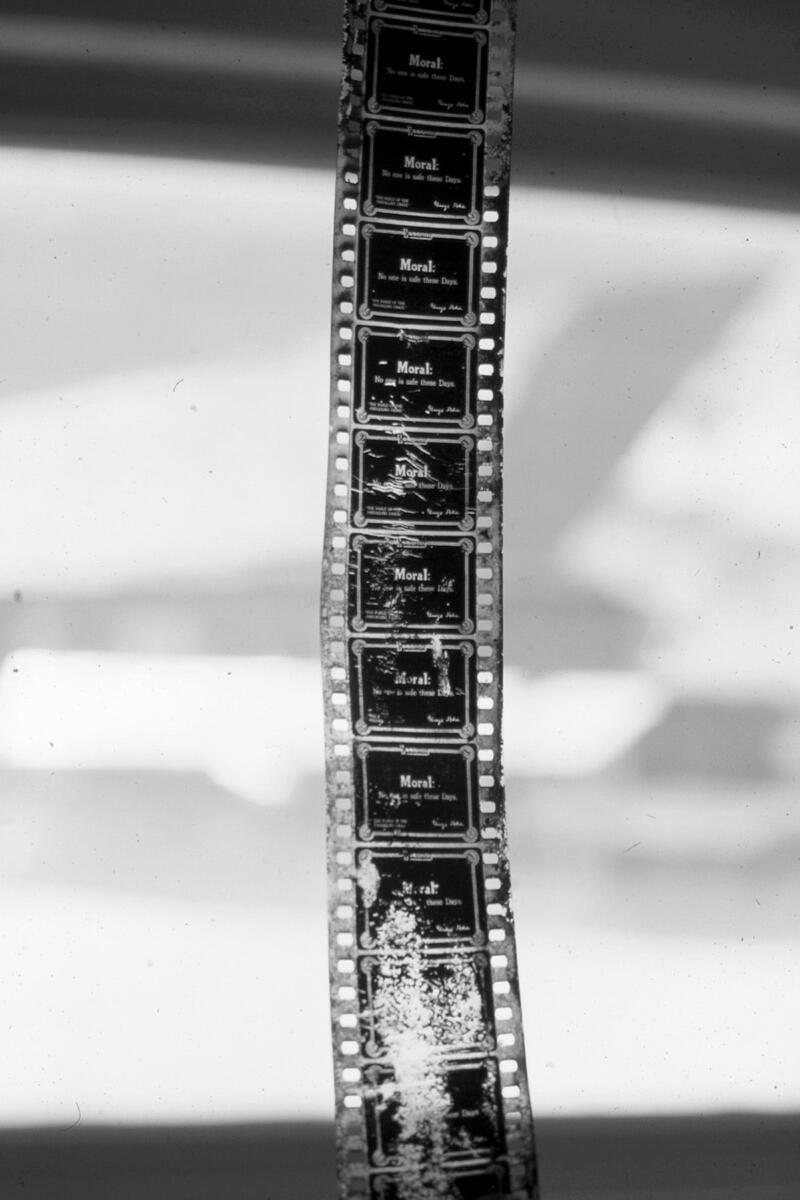

So, the book is more than what its title implies. Yes, Gates was involved in finding a cache of old silent movie films “beneath the permafrost” in Dawson City in 1978, but the story of the discovery and those who made it serve as bookends to this Klondike tale with its cast of colourful characters and historic events.

Here we meet Diamond Tooth Gertie, Swiftwater Bill (“King of the Klondike”), Arkansas Jim, and a vaudeville team called Glycerine and Vaseline. They all figure in Gates’s telling of the history of the Yukon town through the lens of silent film and the early days of theatre in the rough. And Gates is well-qualified to tell it having written several books on the Yukon. In fact, Yukon Commissioner Angelique Bernard was such an admirer that she named Gates Yukon’s first Story Laureate.

Much of the book takes readers on a tour of the feverish gold-seeking years, and there were only a few, when thousands of people rushed north to the Klondike for adventure, the promise of discovery and maybe a shorter life span.

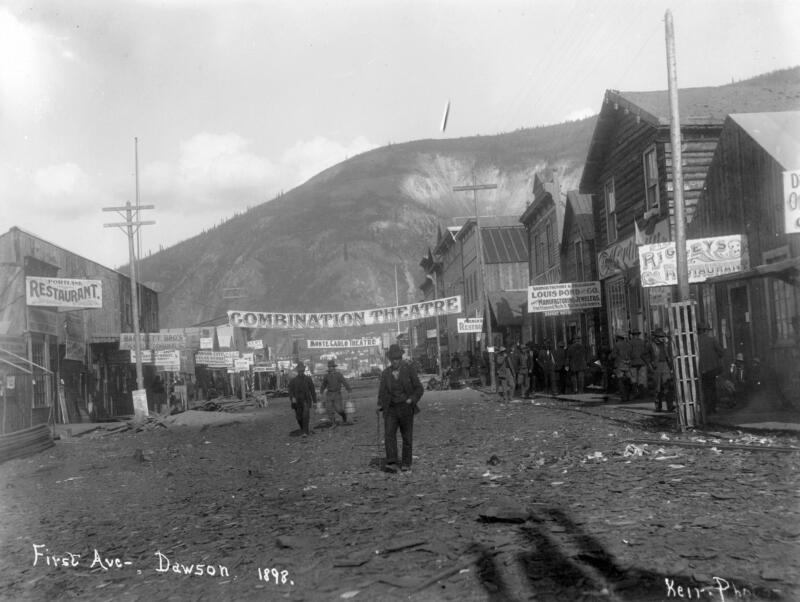

Dawson in the late 1890s was one tough town with only a few men like Colonel Sam Steele to keep the peace and a local judiciary to make sure it was kept. This was a town where hotels and watering holes were built in a hurry and burned down faster. A town where people disappeared never to be heard from again. But it wasn’t all gun play and drunken brawls. The North-West Mounted Police made sure of that.

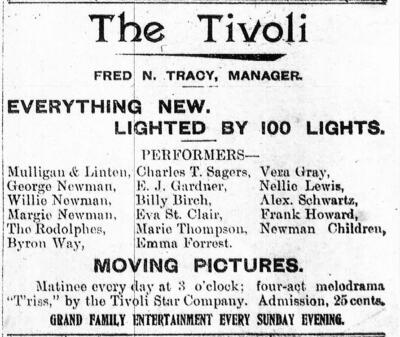

Those who sought more enlightened ways to pass their time in the far north could also choose from several theatres, including an opera house. Places like the Palace Grand, Pavilion, Tivoli, Criterion and Monte Carlo came and went with the latest fire. The names changed with each hopeful new owner.

There was plenty of vaudeville that gave patrons everything from song and dance numbers to wrestling matches, and eventually silent cinema arrived thanks to Thomas Edison and other inventors of the first movie projectors. If patrons tired of the dancehall, they could see a hockey game or take a swim at the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association (the DAAA).

Gates saw the cultural value of digging through entertainment history and describing the various venues that lessened the loneliness of living in a frontier town. It is an aspect of social history that is often overlooked by historians, but is corrected here.

Many of the entertainers of the gold rush days got their start in Yukon theatres. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, for example, or Marjorie Rambeau, who played next to Clark Gable among many other leading men. Gates reserves his highest praise for Cad Wilson “the most popular, even notorious, performer ever to set foot on a stage in Dawson City.”

Most women in this saga of the Wild North are visiting vaudeville entertainers, wives of prominent businessmen, or dance hall show girls. That latter dominated prospector interest. “Female Entertainers had a hard time in the wilds of the sub-arctic forest,” Gates notes, “but they were also amply rewarded by the miners for their display of talents.”

First Nations northerners are acknowledged, with Gates noting that gold mining brought “new religions, new types of land use that were foreign to them, and a new structure of government that ignored the indigenous occupation of the land.” One interesting exception was Kate Carmack, Indigenous wife of prospector George Carmack. She gets credit for helping lay claim to her husband’s “discovery.” Other historians argue that it was Kate who found the gold.

Though the focus of most of the book is the gold rush of the 1890s in Yukon, there are many comparisons to be made in British Columbia with its history of rushes in the Fraser Valley, Caribou, and the silver rush in the Slocan Valley a decade before the Klondike mania.

That is not to say BC plays no part in this story. Many gold seekers and gold diggers travelled through Victoria in search of their share of the gold rush spoils. One of them, Kate Rockwell, a.k.a. Klondike Kate, leased the Orpheum Theatre in the BC capital and claimed she “had the first moving picture in Victoria, a silent machine called a Biograph.”

Also, Gates may not know it, but his heavy reliance on the Dawson Daily News has a loose B.C. connection. One of the newspaper’s founders was W.F. Thompson who had recently gone north after starting the Trail Creek News, the Kootenay smelter city’s first newspaper, in 1895. He knew something about precious metal fever.

Gates returns to the Dawson City Film Find late in the book, explaining how the film was preserved and highlighting the 2016 documentary, Dawson City: Frozen in Time, about the discovery of the long-disappeared footage. Some of it was about the infamous 1919 World Series in which the Chicago White Sox fixed the game. The filmmakers also uncovered the first film to include movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn and the only film appearance of Lillian Russell. Much film history is still to be found, thanks to Gates and many others.

There are others books on gold rushes, but Gates has given readers a different perspective by educating us about the cultural side of the untamed North. His book is a finely produced – and a fun – companion to the more scholarly studies on the period.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker. His forthcoming book Printer’s Devils (Caitlin Press, 2023) tells the 30-year social history of the Trail Creek News, a feisty pioneer newspaper in Trail. His recent book, Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for its Life in Wartime Western Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2022), is reviewed here by Bryan D. Palmer; an earlier book, Codenamed Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb (2018), is reviewed by Mike Sasges. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s work has appeared in The British Columbia Review since it was founded in 2016. He has also contributed an essay to The British Columbia Review on trade unionist Harvey Murphy, and has recently reviewed books by Jesse Donaldson & Erika Dyck, Michael Cone, Bob Williams, Larry Gambone, Terry Gainer, and Marilyn Kriete. Ron lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1553 All that flickered”