1547 Grannies glue the text

China’s Grandmothers. Gender, Family and Ageing from Late Qing to Twenty-First Century

by Diana Lary

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022

$33.95 / 9781009064781

Reviewed by Isabel Nanton

*

In a China-West binary, Diana Lary, Professor Emerita of Modern Chinese History at the University of British Columbia, blends in her latest — and she says her last – book, solid scholarship with contemporary immediacy and a warm humanity. Having initially lived in China from 1964-65, subsequently in the Eighties and touching down in 2010 as part of a delegation to China led by Canada’s then Governor General Michelle Jean advocating for women workers, Lary casts her net wide while examining this late Qing (1911) to 21st century time, focusing on the pivotal role of grandmothers “without the legion [of whom] China’s sustained economic boom would have been impossible.”

In a China-West binary, Diana Lary, Professor Emerita of Modern Chinese History at the University of British Columbia, blends in her latest — and she says her last – book, solid scholarship with contemporary immediacy and a warm humanity. Having initially lived in China from 1964-65, subsequently in the Eighties and touching down in 2010 as part of a delegation to China led by Canada’s then Governor General Michelle Jean advocating for women workers, Lary casts her net wide while examining this late Qing (1911) to 21st century time, focusing on the pivotal role of grandmothers “without the legion [of whom] China’s sustained economic boom would have been impossible.”

“Cheap, disciplined labour is the foundation of China’s economic miracle,” she states — concurrently contributing in her text to a deeper understanding of Chinese culture with a scholarship worn lightly.

A grandmother herself, Lary blends into the narrative her own relationship with her “three treasures,” two golden boys and one jade girl grandchildren to whom the book is dedicated, concluding with a chapter of autobiographical notes tracing her own life through some of the major themes and phases already examined in the main text — such as archetypes and images of grandmothers, child care, ruling the roost, old age, grandfathers, transmitters of culture, absent parents, the pleasures of old age and leaving this life. That her paternal granny and Empress Dowager Cixi both smoked the same brand of “Passing Clouds” cigarettes is one of Lary’s several endearing insights in this coda.

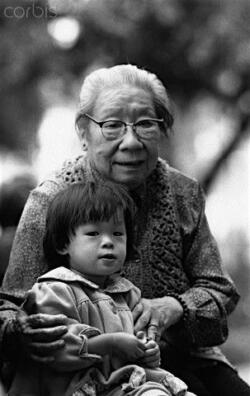

Migrations are Lary’s forte, this work covering the beginnings of industrialization at the end of the Qing Dynasty, leading to the reform era, starting in the early 1980s since when hundreds of millions of peasants left home to go work in factories, leaving legions of grandmothers to raise their children, whom parents see on their two weeks holiday a year. Since China’s population more than doubled during the Qing Dynasty, Lary gives broad-stroke background to include the Mao Era when the population doubled to almost a billion, the Great Famine in the 1960s, and the decade of the Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976.

Structurally, the demystifying of communist society is made easier to absorb by a series of boxes in each chapter. The short Child Care chapter, for instance, has three boxes covering baby talk, including Liu Simu, star of the Marvel movie Shang-Chi, whose parents went abroad to study for the first five years of his life while he basked in the “warmth and undemanding love of his grandmother in China,” and from 1949 the mighty four-decade long rule of Flying Pigeon brand bicycles, when “China was the kingdom of bicycles.”

Seamless injection of her own viewpoints save Lary’s book from any taint of scholarly stuffiness on the role of grandmothers, who are the glue that holds the text, and indeed the country, together. Lary states categorically that, during the war with Japan, which ended in 1945, and before the civil war won by the communists in 1949, many women were confined to their homes, “for fear of being kidnapped and sent as sex slaves (I refuse to use the insulting term ‘comfort women’) to Japanese army brothels.”

Other tough themes discussed including foot-binding and “son-preference,” which guarantees a woman care in her old age. Urban Chinese women retire at 50, the expectation being that they will be raising the next generation. Their expertise is unquestioned as purveyors of culture: they tell children stories to give them a sense of where they come from; they are health experts regarding matters as diverse as galactogogues (milk stimulating foods for new mothers); and they are grannies “locked in a battle” with evil spirits who might threaten a newborn. Grandfathers merit a chapter of their own with a look at the perils of polygamy and the place of concubines.

Midway through the book, I learn that in China grandparents are protected by law: children and grandchildren have a duty of care for their parents and grandparents under Article 28 of the 1980 Marriage Law. Through the Twenty-Four Filial Exemplars middle-aged Chinese citizens are urged to “practice a new code of care for their parents.” These sound – well — most sound! Exemplars include listening to your parents’ reminiscences carefully, teaching them how to get on the net, talking openly to our parents about your love for them and phoning them once a week, taking them for regular physical checkups and buying appropriate insurance for them, taking them on trips to their old homes, taking them to see old films, and making frequent emotional connections with them — as Lary does with her reader in this fine book.

*

Kenyan-born author and Cambridge Press Fellow Isabel Nanton specializes in writing about East Africa and Western Canada. She has also reviewed books for the The Globe and Mail, The Vancouver Sun, and Old Africa magazine in East Africa. Editor’s note: Isabel Nanton has also reviewed a book by Kogila Moodley for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1547 Grannies glue the text”