1514 Sternwheeler majesty

Connecting the Kootenays: The Kootenay Lake Ferries. A Hundred Years of Service, 1921-2020

by Michael A. Cone

Nelson: Maa Press, 2022

$45.00 / 9781778350511

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Sternwheeler Majesty: A century of sailing the Kootenays on the “boats” that plied the region’s waterways

Sternwheeler Majesty: A century of sailing the Kootenays on the “boats” that plied the region’s waterways

My childhood memory of the bygone era of sternwheelers on Kootenay waterways begins at the end of Michael Cone’s exhaustive pictorial account of the ferry system that tied the region’s mines, forests, and people together for 100 years.

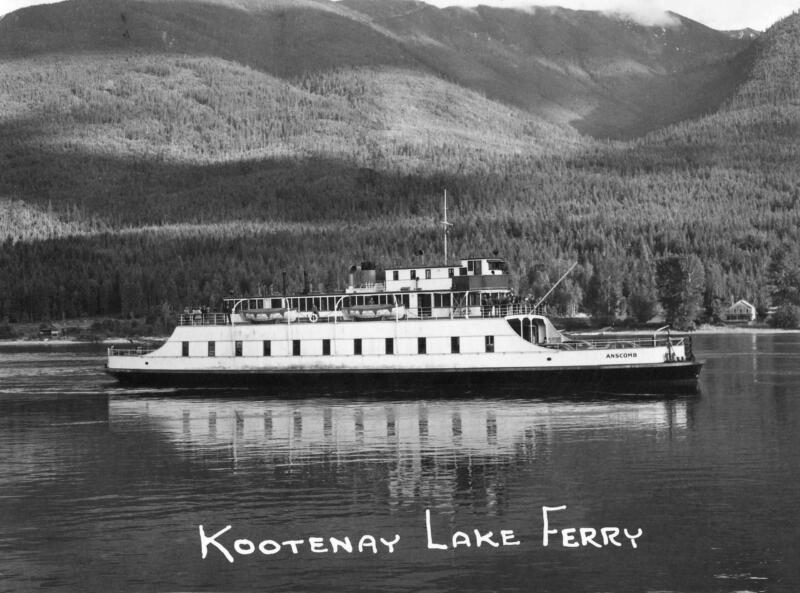

I recall waiting on the shore of Kootenay Lake at Balfour on a hot summer’s day where the metal-hulled Anscomb would dock to take us across in our old 1951 Ford to Kootenay Bay on the eastern shore of the 60-mile-long lake.

It isn’t the largest, the cleanest or even the deepest of B.C.’s lakes, but it can fairly claim to be one of the most beautiful. And author Cone gives us plenty of visual and factual reasons why that is so. In fact, the large-sized book offers photographs, maps, and other helpful guides to assist in appreciating the age of the sternwheeler.

I never saw the Nasookin, the multi-decked early sternwheeler in the region, so seeing the extensive photo collection that featured it from many angles and eras was a special treat. Reading about its 16 years from 1931 to 1947 as the lake ferry, I could visualize its tall presence as it plied those waters, docking at small villages along the way.

There was a romantic feel to the Nasookin, and Cone spends much of the first half of his book sharing it with us. It was the largest of the “three queens” of the Kootenays, he writes. The other two were the Kuskanook and the Sicamous.

“Ranchers and homesteaders relied on elegant sternwheelers that regularly called at nearby landings for the mail, supplies and travel to and from Nelson,” Cone writes. His description extends to the early days of the automobile and motorists’ demands for better roads and faster ferries.

Back in the 1890s, “two railway giants, the CPR (Canadian Pacific Railway) and the Great Northern, were locked together in a competitive bid to control the rail and steam lines serving the West Kootenays,” Cone explains. The CPR’s Kootenay and Columbia Railway eventually won that war and it transported silver hunters, gold diggers and settler families to the region with help from the Columbia and Kootenay Steam Navigation Company.

Cone documents the history of the ferries that connected the natural resources of the Kootenay-Columbia River systems to markets to the west and south when there was no other way to efficiently get there. His book necessarily covers capitalist development of region as well as its displacement of First Nations who had lived in the region for millennia.

The great sternwheelers represented progress in the old days and the book is chockablock full of statistics, marking each advance and inexorably each step toward the demise of the boats. Eventually their time would end as the Southern Highway tied the entire system together.

It is difficult to imagine today what passage on the lake boats would have been like, but Cone helps us do so. Passengers could enjoy the ride in a stateroom and enjoy meals in a well-equipped dining room. On deck, they could watch the crew of able mariners keeping the ship afloat, as Cone admiringly describes.

Male travellers enjoyed a smoking lounge while women could partake of “the long-standing practice of serving afternoon tea in the ladies parlour at three o’clock.” There were spittoons in the men’s lounge and an upright piano in the ladies.

“Amidships, between the men’s smoking room and the ladies’ parlour, was the showpiece of the steamer, her dining saloon,” Cone explained. Here, the large rectangular tables covered in spotless white linen were adorned with place settings of monogrammed china, gleaming polished silverware and folded napkins.”

The menu could include clam chowder, stuffed baked salmon, baked potatoes, fresh vegetables, French pancakes for dessert, finishing with Stilton or McLaren’s cheeses. A full staff of servers and cooks prepared the meals that gave the sailings an elegance that attracted tourists far and wide.

As I completed this review, I had just visited the last of the big “boats” at Kaslo, the sweet little Kootenay Lake town where the old Moyie is docked. It has been preserved as a museum. Farther down the lake near Nelson, parts of the Nasookin have been converted into a home.

Michael Cone’s book had more fully informed me to enjoy the visit, but I was both pleased to see the old-time vessel and saddened that she was covered in scaffolding. She was long overdue for a refurbishing.

Between the planks that partially hid her, I could still see the decks that once teemed with travellers, everyone needing to traverse massive Kootenay Lake, stopping at the many destinations along the route before debarking en route to Creston.

As I cast an eye over her nose and the big wheel at her stern, I envisaged the scenes author Cone writes about so lovingly. Now history provides a docking place for these once majestic vessels.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker whose latest book, Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for its Life in Wartime Western Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2022), is reviewed by Bryan D. Palmer; an earlier book, Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb (2018), is reviewed by Mike Sasges. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s work has appeared in The British Columbia Review since it was founded in 2016. He has contributed an essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy and has recently reviewed books by Bob Williams, Larry Gambone, Terry Gainer, Marilyn Kriete, Michael Neitzel, and Peter J. Smith. Ron lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1514 Sternwheeler majesty”