1505 Vancouver’s neighbourhood hubs

Neighbourhood Houses: Building Community in Vancouver

by Miu Chung Yan and Sean Lauer (editors), with a foreword by David Hulchanski

Vancouver, UBC Press, 2021

$32.95 / 9780774865821

Reviewed by Jennifer Chutter

*

The text opens with a compelling question: “What would it be like to live in a welcoming community?” It is a provocative start to their examination of neighbourhood houses because it recognizes that most people do not live in communities that they would define as welcoming, which places the reader in the role of evaluating and re-evaluating their own place within their current neighbourhood as they read through the work. This five-year mixed-method study involved a multi-disciplinary team from several universities who worked collaboratively with staff from Vancouver neighbourhood houses to develop “research questions, strategies, approaches to collecting data, and strategies to disseminate findings” (p. 253). This study was developed in response to the Vancouver Foundation’s Connection and Engagement report released in 2012, which revealed that most Vancouverites did not have a strong sense of community or connection to each other. Yet despite these findings from the Vancouver Foundation, this study illustrates how neighbourhood houses offer localized counter-narratives to the seemingly lack of connection and engagement in civic life.

The text opens with a compelling question: “What would it be like to live in a welcoming community?” It is a provocative start to their examination of neighbourhood houses because it recognizes that most people do not live in communities that they would define as welcoming, which places the reader in the role of evaluating and re-evaluating their own place within their current neighbourhood as they read through the work. This five-year mixed-method study involved a multi-disciplinary team from several universities who worked collaboratively with staff from Vancouver neighbourhood houses to develop “research questions, strategies, approaches to collecting data, and strategies to disseminate findings” (p. 253). This study was developed in response to the Vancouver Foundation’s Connection and Engagement report released in 2012, which revealed that most Vancouverites did not have a strong sense of community or connection to each other. Yet despite these findings from the Vancouver Foundation, this study illustrates how neighbourhood houses offer localized counter-narratives to the seemingly lack of connection and engagement in civic life.

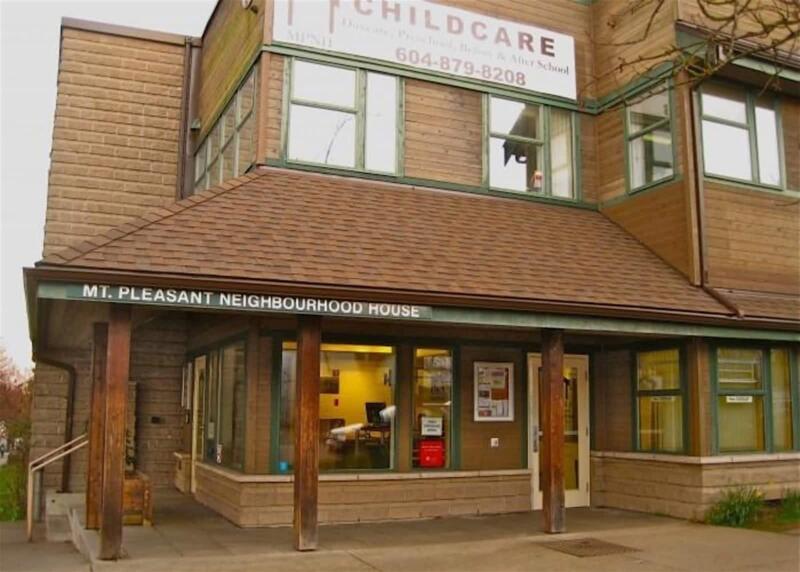

Neighbourhood houses are defined as “a service hub with long service hours that makes them accessible to local residents, even to those who go to school or work. Based on a holistic perspective, they organize and provide low-cost services to different groups of residents to meet individual and collective needs in the community” (p. 100). They operate in a similar manner to a community centre, with a range and variety of programming for all ages, but the programs are often developed by residents in the community to meet a specific and particular need, which creates more inclusive and dynamic programming.

For example, Wen Ling, a recent Taiwanese immigrant attending Kits Neighbourhood House, was encouraged to draw on her previous degree to start an art therapy program, which provided her with the self-confidence to volunteer and develop other programs (p. 194). This edited collection of essays provides a comprehensive view of the expansion of neighbourhood house movement in Vancouver, how they have changed, their organizational structure, and their program offerings, though the content of the essays frequently overlaps in the chapters, which becomes repetitive.

The Neighbourhood House movement began in England in 1884 with the establishment of Toynbee Hall in East London with the aim of raising up the working classes by having mostly male university students living with them in order to create a “mutually beneficial” relationship, where the upper classes could gain a better understanding of poverty and social conditions, and the working class could attend lectures and classes (p. 33). As the movement spread to the United States, settlement houses became more women-led, with the best-known was Hull House in Chicago, run by feminist Jane Addams (pp. 30, 35). Unlike the English and American counterparts, settlement houses in Canada “did not have a clear mandate for social reform and political advocacy” (p. 61). They instead focus more on providing community services to ensure integration into Canadian culture. The first one was established in Vancouver in 1938, but was called a neighbourhood house instead of settlement house and had little religious connection.

In the Great Vancouver Area there are now 16 active neighbourhood houses, with some belonging to the Neighbourhood Houses Association and some remaining independent. The development of place-based social support services has spread worldwide, and many belong to the an International Federal of Settlement and Neighbourhood Centres, which represents over “10,000 members from over thirty countries” (p. 30).

It is clear from this comprehensive study that neighbourhood houses in the Greater Vancouver area deliver tremendous value to the local community by providing services to support the residents integrating into the neighbourhood; they “have a critical role in identifying what services are required and what infrastructure needs to be put in place to produce an effective support system” (p. 69). Additionally, they “reflect the diversity and changing nature of the communities where they operate” (p. 70).

In Vancouver, neighbourhood houses collaborate closely with the Social Planning department, and have become important “community partners” by “connecting municipal authorities with actors on the ground” (p. 79). They have an integral role in ensuring that services offered meet the needs of the community, and that future planning decisions are reflective of the place they will be implemented in. This collection of essays presents deep insights into how Vancouver could create a stronger sense of community by investing more in the programs that work.

In a culturally diverse city, like Vancouver, the examples presented illustrate the ways in which racialized immigrant women and young people have gained a sense of place and belonging within their local areas through participating and volunteering in programs at neighbourhood houses is particularly important, though more could be developed as to how these kinds of opportunities are examples of meaningfully encouraging diversity, equity, and inclusion within their community. This lack of interrogation of larger issues becomes problematic because it appears from the study that while women are predominately the users and workers within neighbourhood houses, they do not appear to be many in the paid or permanent leadership roles, as the named directors are male.

For example, one interviewee comments about the lack of pay; this should be examined in greater depth because it speaks to an awareness of the multi-layers of inequity in the city, and the difficulty of finding employment that provides a living wage, especially for immigrant women. This lack of examination of possible structural inequities makes it difficult to see how neighbourhood houses have grown and are not merely perpetuating outdated gender norms when it comes to positions of leadership or power.

There was a large survey sample of 675 people, and I am curious as to what it might have suggested that could be improved or maybe how it didn’t meet their needs. Nor did the study appear to address ranges of gender expression or sexuality, as the interviewees cited reflect a heteronormative view, which is important to examine when looking at whether people feel a sense of belonging and attachment to their neighbourhood. The main weakness of the text is the way in which Chapters 5 and 6, while distinctly different in focus, draw on many of the same interview quotes to support their arguments. This is repetitive, and it dilutes the validity of the fact that they claim to have interviewed over 40 people. When put together in the same collection, it appears that the interview process was not successful as they are overusing the same pieces of evidence to justify different arguments. This is further compounded by a lack of interrogation of the claims made, or the teasing out of nuance. It would also be helpful to read responses which maybe showed a negative response to neighbourhood houses in order to acknowledge the outliers that the survey sample indicates (p. 111). Citing a broader range of voices would create a more nuanced argument of the importance of place-based community building.

While neighbourhood houses appear to add value to their local communities, they are inconsistently funded, and rely on yearly grants to maintain their programming. Since the funding schemes need to be renewed on a yearly basis, long-term planning difficult, and it is challenging to maintain staff because contracts are often temporary. This places undue stress on a seemingly well-functioning and economical system of support services that strives hard to create a welcoming community.

Yan and Lauer contribute an important study countering the perception that Vancouver is a difficult city to form attachments to by illustrating that people want to feel a sense of belonging, and to give back to the community that has cared for them during often difficult and turbulent times. It is easy to point out systems and structures that are not working, but neighbourhood houses provide many examples of what does work to nurture a truly welcoming community by building relationships and empowering others to share their hidden strengths. As the City of Vancouver continues to develop neighbourhood plans, Yan and Lauer’s Neighbourhood Houses: Building Community in Vancouver provides an important collection of essays reminding us that cities are made up of people with complex needs and desires, but who want to connect and support each other when given an opportunity to feel safe to do so.

*

Settler Jennifer Chutter is an award-winning PhD candidate at SFU. Her dissertation research is on the formation of the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) and how they advocated for their sense of home and place within in the neighbourhood. Their agency and activism bring to light the legacy of colonial structures within the city and emphasize the importance of preserving and designing neighbourhoods to foster a sense of belonging and inclusion. Her previous research was on the Vancouver Special and its importance as a localized form of architecture. She feels most at home in Vancouver when she smells the salty air while running along the seawall. Editor’s note: Jennifer Chutter has recently reviewed books by Jak King, Kate Braid, Emma Fitzgerald, Iona Whishaw, Dave Doroghy & Graeme Menzies, and T.K. (Justin) Ng for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1505 Vancouver’s neighbourhood hubs”

Very pleased to know that Cedar Cottage Neighbourhood House is finally moving ahead on their long-planned expansion. I’ve been involved with them, off and on, for a long time.