1091 In praise of city neighbourhoods

Battleground Grandview: An Activist’s Memoir of the Grandview Community Plan, 2011-2016

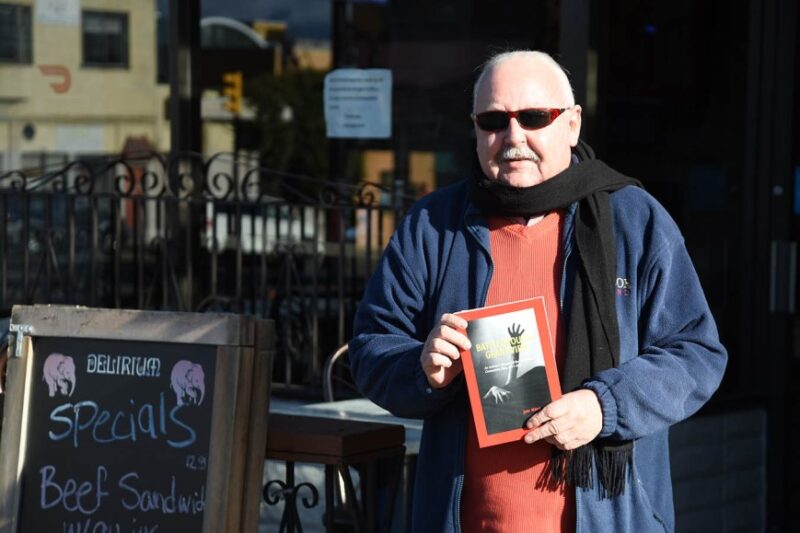

by Jak King

Vancouver, The Drive Press, 2020

$25.00 / 9780986778209

Reviewed by Jennifer Chutter

*

Planning for housing in Vancouver is a contentious issue due to conflicting ideas of where increased density should take place, what styles of housing are needed, and who should get access to it. Overshadowing these conflicting ideas is the lack of affordability for both homeowners and renters. It is into the melee that Jak King inserts Battleground Grandview: An Activist’s Memoir of the Grandview Community Plan, 2011-2016, a close examination of the failures of a municipal redevelopment scheme in the neighbourhood of Grandview-Woodlands. King weaves together his own personal accounts with newspaper articles, interviews, and city documents to give a well-supported view of the City of Vancouver’s poorly executed process of attempting to involve residents in the Community Plan for the Grandview-Woodlands neighbourhood.

Planning for housing in Vancouver is a contentious issue due to conflicting ideas of where increased density should take place, what styles of housing are needed, and who should get access to it. Overshadowing these conflicting ideas is the lack of affordability for both homeowners and renters. It is into the melee that Jak King inserts Battleground Grandview: An Activist’s Memoir of the Grandview Community Plan, 2011-2016, a close examination of the failures of a municipal redevelopment scheme in the neighbourhood of Grandview-Woodlands. King weaves together his own personal accounts with newspaper articles, interviews, and city documents to give a well-supported view of the City of Vancouver’s poorly executed process of attempting to involve residents in the Community Plan for the Grandview-Woodlands neighbourhood.

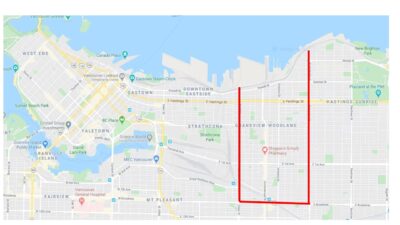

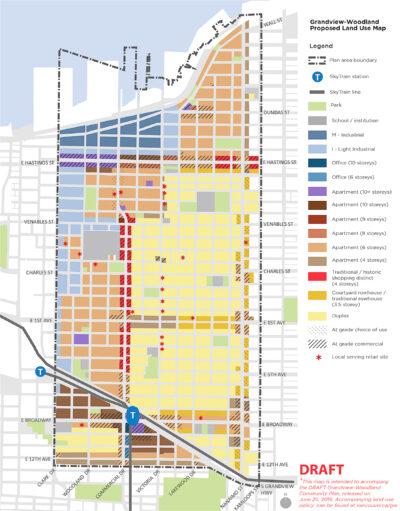

King’s dense work is written for an audience with some familiarity with the five-year struggle and of the neighbourhood itself. Maps, photos, and a Who’s Who list would have enhanced the readability of Battleground Grandview because it was difficult to keep track of unfamiliar locations and people. While it is easy to get bogged down in the myriad of details, the three intertwined undercurrents throughout the book are worth contemplating and extrapolating. While not explicitly laid out, I suggest that the larger aim of the work is an attempt to highlight the difficulty of defining who the city is for, what is a neighbourhood, and who is an expert.

Though Battleground Grandview is laid out chronologically, I have approached my review thematically in order to highlight the difficulty in answering these three key questions that King develops implicitly throughout his examination of the failures of urban planning in the Grandview-Woodlands neighbourhood.

Who is the city for? One of the central issues that repeatedly comes up in King’s discussion is the idea of who the city is for. From the City of Vancouver Planning department’s perspective, the city is for the future residents and not for the current ones. It is clear throughout King’s work that current residents are disregarded as having any sort of role in creating the current vibrancy and functionality of the city; furthermore, the poor are unacknowledged. The Grandview-Woodlands Community Plan focuses on the need to provide housing for the imagined future residents to the city, and the assumption is that they will be middle-class and would prefer to live in tall towers. From a developer’s point of view, tall towers are the most profitable form of housing, and they make up significant portions of Vancouver’s existing domestic landscape, notably in Yaletown, Coal Harbour, and the emerging Oakridge development. King is not against the construction of residential towers, but he does question the feasibility of the Community Plan which neglected to think through what those future residents would need in terms of transportation, accessibility to other amenities, and the need for commercial areas to support them.

For example, putting in towers at the corner of Broadway and Commercial at the Skytrain station places an increased burden on the surrounding area, and there was no planning for green spaces or other features to create a sense of home for people. King argues that lower income neighbourhoods bear the brunt of urban growth, but areas of the city with larger lots — which could arguably accommodate more housing — are protected. As a result, urban growth is uneven across the city, which creates further inequities as transit systems and community services, along with water and sewage, face greater demand than they are designed for. King’s argument challenges the reader to think through the larger political machinations that are guiding urban growth and the impact it has on smaller neighbourhoods.

What is a neighbourhood? King does a strong job emphasizing the difficulty of defining what constitutes a neighbourhood. He suggests that Grandview-Woodlands is actually a collection of six different overlapping areas, all of which have different needs and features worth saving, but which collectively form a symbiotic whole. According to King, City planners misunderstand the complexity of planning for urban growth because they don’t account for the interconnectedness of people and structures. The problem with the initial Community Plan was that it homogenized the entire area and flattened out the distinct features that make the neighbourhood unique, and there appeared to be little understanding that changes to one area would impact the whole. Therefore, a broad uniform approach with respect to heights and densities cannot be implemented across the neighbourhood because it will impact the smaller areas in different ways. While residents are not against change and recognize that all neighbourhoods go through cycles of growth and development, they “want these changes to be under [their] control and guidance” (p. 33).

King places these comments within a historical context by discussing how Grandview-Woodlands changed during the 1950s with the arrival of many residents from Strathcona after their houses had been expropriated during urban renewal. Throughout, King describes a neighbourhood that has both controlled and accommodated urban growth and change by advocating for people’s need to have affordable housing and a variety of accessible urban amenities. King argues that Grandview-Woodlands did not need to make sweeping changes because the residents, as part of the Grandview-Woodlands Area Council, had spent decades thoughtfully planning for urban growth.

Who is an expert? Lastly, King examines who is considered an expert when it comes to neighbourhoods. Is it City Planners? City Council? Or residents? Within his discussion he highlights the complexity of Vancouver’s political system, and how decision-making is frequently stalled by City Council, which has its own party agenda. City Planners have a huge impact on the quality of life for the residents in the city, but they are appointed rather than elected by residents, and they receive their directives from City Council. King also calls into question the long-standing pattern of city officials supporting developers’ desires to maximize profits in new construction and their lack of accountability to the current residents living where the new development will occur. When the residents protested the sweeping changes proposed for their neighbourhood, the City Planning department quickly agreed to put together a Task Force and host a series of workshops in order to gather residents’ feedback.

However, King points out that the process was flawed because City Planning department staff facilitated the workshops, but the reporting out did not accurately reflect the wishes, ideas, or insights of those who actually lived in Grandview-Woodlands, nor did the residents always understand the implications of planning decisions. Planners were seeking “responses rather than ideas” (p. 21). As the protests continued, in order to foster greater community involvement in planning, one of the solutions proposed by the Planning department was to host ten Saturdays of meetings over the summer. This excluded people who worked; furthermore, the meetings were all in English “in one of the most diverse neighbourhoods in Vancouver… according to Statistics Canada” (p. 155). Despite hundreds of residents giving up their time to participate in events hosted by the Planning Department, their expertise from living within the neighbourhood for years was denied as having any value.

The discussion of the formation and activism of the No Tower Coalition poses the most interesting microanalysis of all the neighbourhood disputes and ties together the complexity of planning for urban change. The Kettle Friendship Society, a long-standing organization within the neighbourhood, partnered with Boffo, a local developer, to expand their existing building at Adanac and Venables. Boffo would offer thirty new units as well as new meeting places to Kettle Friendship Society in order to expand their supportive housing services for the mentally ill in exchange for building market housing on the existing site. While Boffo was vague about the height of the towers—proposals ranged from 12-20 storeys—it was clear to residents that, regardless of height, the new development would significantly impact the views of the mountains for the whole neighbourhood. The No Tower Coalition advocated for lower density housing to be put in to ensure Kettle could expand their existing facilities, while also ensuring that the overall neighbourhood aesthetic would not be altered.

However, the No Tower Coalition’s pushback against the Boffo development was frequently twisted as a lack of support for Kettle and the mentally ill. King raises some thoughtful points about the lack of government support — federally, provincially, and municipally — for mental health funding when a non-profit agency wants to expand its services. As a result, partnering with a private developer is a boon for non-profits who have few options, and who often rely on grants and donations to provide services. The No Tower Coalition ties together the residents’ expertise as a result of decades of neighbourhood advocacy and exposes the failings of the municipal government to care for the most vulnerable.

As Battleground Grandview repeatedly stresses, the City of Vancouver needs to engage with its current citizens in meaningful ways to plan for future growth. This includes providing mail-outs as “one part of a multi-faceted, multilingual, and multicultural outreach communication strategy” (p. 123) of any proposed changes in a given area, as well as expanding communication by providing flexible ways to gather feedback, using facilitators who are not City of Vancouver employees to run Open Houses, and being transparent throughout the decision-making process. The rise in citizen action groups across the city indicates the strong attachment of residents to where they live and a desire to remain within their neighbourhood.

In Battleground Grandview, Jak King presents a strong call to action: it is time for the City of Vancouver to take into consideration the needs, wishes, and desires of current residents to maintain the vibrant areas of the city, rather than persistently planning for future urban growth in the form of tall towers.

*

Settler Jennifer Chutter is an award-winning PhD candidate at SFU. Her dissertation research is on the formation of the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA) and how they advocated for their sense of home and place within in the neighbourhood. Their agency and activism bring to light the legacy of colonial structures within the city and emphasize the importance of preserving and designing neighbourhoods to foster a sense of belonging and inclusion. Her previous research was on the Vancouver Special and its importance as a localized form of architecture. She feels most at home in Vancouver when she smells the salty air while running along the seawall. Editor’s note: Jennifer Chutter has also reviewed books by Kate Braid, Emma Fitzgerald, Iona Whishaw, Dave Doroghy & Graeme Menzies, T.K. (Justin) Ng, and Chelene Knight for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1091 In praise of city neighbourhoods”