1479 Play time

Sea of Tranquility

by Emily St. John Mandel

Toronto: Harper Collins Canada, 2022

$29.99 / 9781443466097

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

In the first paragraphs of Part 1 of Sea of Tranquility, dated 1912, a young man named Edwin St. John St. Andrew stands ‘with gloved hands’ on the upper deck of a mid-Atlantic steamship, yearning for the unknown. We’re told he’s been sent ‘into exile,’ and also that he’s been formally educated at the ‘best schools,’ meaning British. Each of these statements appears so matter-of-fact that it would be easy to skip over the way each of the observations ends: but he locates greyness instead of difference, but exaggeration is at least a little true, but his ‘secretly radical views’ will speed up his fate. Those three buts are critical: they tell us not to believe what’s happened already and likely not anything that follows either. Or else to believe it but believe in alternatives as well, perhaps those that we haven’t even thought about yet. At the same time. Which is a conundrum.

In the first paragraphs of Part 1 of Sea of Tranquility, dated 1912, a young man named Edwin St. John St. Andrew stands ‘with gloved hands’ on the upper deck of a mid-Atlantic steamship, yearning for the unknown. We’re told he’s been sent ‘into exile,’ and also that he’s been formally educated at the ‘best schools,’ meaning British. Each of these statements appears so matter-of-fact that it would be easy to skip over the way each of the observations ends: but he locates greyness instead of difference, but exaggeration is at least a little true, but his ‘secretly radical views’ will speed up his fate. Those three buts are critical: they tell us not to believe what’s happened already and likely not anything that follows either. Or else to believe it but believe in alternatives as well, perhaps those that we haven’t even thought about yet. At the same time. Which is a conundrum.

But that’s the point. As readers, we’re being asked to play Time. As though the writer is saying: Try to be ready for it: the game’s about to begin. Or maybe it’s already started — you never can tell.

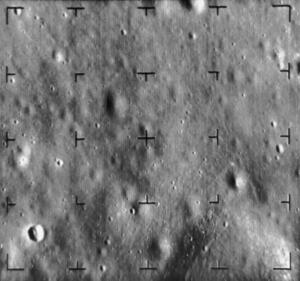

Take the ‘Sea of Tranquility,’ for example. It was first named on a 1651 lunar map, for the ‘flat plain’ that was actually the consequence of a meteoric crash site, but perhaps is better known now as the site of the Moon landing in 1969, where Neil Armstrong left his flag and his footprints. But both these dates are peripheral (and ‘tranquility’ on a crash site is at the very least suspect). In the novel, the Sea is the site where we’re told that ‘the first moon colony’ was built — near where ‘the Apollo-11 astronauts had landed in a long-ago century.’ This isn’t 1969 anymore.

Apparently.

But when and where are we? Mandel’s narrative takes place at various times. In 1912 and over the following few years, to start, which is when it deals with the ‘double-sainted’ character named Edwin and touches on empire and the BC wilderness. (Captain George Vancouver on the ship Discovery in 1793 later gets an earlier mention: I said be ready: it’s that kind of book.) The novel also happens in 2020, where it follows a woman named Vincent and a 21st century Ponzi scheme, and in 2203, where it traces Olive Llewellyn’s book tour through Manhattan, Toronto, the Republic of Texas, and elsewhere (she already knows her way around Colony One on the Moon). Olive has published a novel called Marienbad (which is the name of a 19th century Czech spa, known for its Jewish settlement and the later Nazi destruction, and also for a 1961 Alain Resnais film, praised for its narrative ambiguities). Critically, Marienbad (the fictional novel) deals with a fictional pandemic, and the book tour is taking place just as a real-life pandemic is about to hit. And then does hit.

But when and where are we? Mandel’s narrative takes place at various times. In 1912 and over the following few years, to start, which is when it deals with the ‘double-sainted’ character named Edwin and touches on empire and the BC wilderness. (Captain George Vancouver on the ship Discovery in 1793 later gets an earlier mention: I said be ready: it’s that kind of book.) The novel also happens in 2020, where it follows a woman named Vincent and a 21st century Ponzi scheme, and in 2203, where it traces Olive Llewellyn’s book tour through Manhattan, Toronto, the Republic of Texas, and elsewhere (she already knows her way around Colony One on the Moon). Olive has published a novel called Marienbad (which is the name of a 19th century Czech spa, known for its Jewish settlement and the later Nazi destruction, and also for a 1961 Alain Resnais film, praised for its narrative ambiguities). Critically, Marienbad (the fictional novel) deals with a fictional pandemic, and the book tour is taking place just as a real-life pandemic is about to hit. And then does hit.

Turn the page and Sea of Tranquility is also set in the year 2401, mostly on Moon Colony Two, near the Time Institute, not far from the Night City and the Periphery, under a dome, where two other characters, Gaspery and his sister Zoey, live (or live part of the time, time itself being both rigorously ordered and inherently plastic). Contained, because we’re told of an upsetting threat (life on the Moon has been infected by yet another pandemic). Plastic, because threat is likely what always happens. Or, put another way, what happens in 2401 is also causing something to happen in other times as well: it seems an ‘anomaly’ has been found in the Time Institute’s secret computer program — which is to say, an ‘infection’ of a different order. Both in 2012 and during all the other times, some blip intrudes (or has intruded) into the normal sequence of what was expected to happen, meaning that Time Travel is real and the normality of the Future is in question.

Mandel combines her shrewd observation of events in the present moment (e.g., emigration, economics, technical challenge, deception) with a lively imagination (probing ‘What if?’ and ‘What then?’) — skillfully rendering characters through plain text and exposing their more or less familiar desires, rivalries, and flawed bureaucracies, to the point that all those narrative leaps across time come to seem as reasonable as not. I suspect there is room for a few stiff questions here, but I don’t claim to be a physics expert. It’s the appeal of the events that matters. Puzzling to begin with, the seemingly separate incidents will likely keep most readers reading to the end in order to see how they all connect. (‘The end?’ the book asks, still playing with time.)

Many readers will be familiar with Mandel’s hugely successful previous books, including Station Eleven, which was recently adapted to television, and which also grapples with issues of pandemic and a future-world. I suspect that Sea of Tranquility will probably soon be optioned for film if it hasn’t been already (my perfectly clear sentence is craftily muddled by tense and temporality). I also think that the novel, for all its imaginative leaps to start with, resolves itself more or less the way a familiar detective novel does (think Agatha Christie, P.D. James), with all the characters lined up for resolution (except for those whom we haven’t remembered to watch out for along the way). I see this as a cogent description of Mandel’s book, not as a critical mistake. For some readers it will be pleasingly satisfying.

Myself, I liked best the artful asides, as when a man at a cocktail party (referred to only as ‘the fedora’) says ‘I think I’ve seen you before’ and the reader hears at once the emptiness of the pickup line and the possibility of time travel (‘and what is time travel, if not a Security problem?’) Or hears the reverberations of an old person’s sigh: ‘the things you see when you’re young.’ Or analyzes the presumptive accuracy of the confident second-guesser: ‘after that, how could you not have known?’ Time plays on.

Alert readers will hear Mandel’s Canadian ironies as well — those that have been encountered in history books or honed at cocktail parties or remembered from book tours? The crew of the Discovery, for example, who on finding ‘empty’ wilderness on the West Coast, don’t recognize (can’t tell) that the ‘empire’s’ smallpox epidemic is the cause of what they perceive as emptiness. Another describes a woman’s work as a writer: ‘my job was to sit there all day, rewording unfortunate sentences’ (so that you can’t tell where a flaw was, or a ‘file corruption’ may have been?) And yet another irony — evocative, tiered (multi-storied?) — shows up in the transcript of a conversation between an interviewer who assumes he knows more than he actually does and a time-traveller from the future (one from Canada, perhaps) who in fact does know more but who can’t tell: i.e. is not supposed to say. No matter: the interviewer isn’t actually listening.

The questioner asks: ‘And your affiliation, what institution was that again?’

The writer answers: ‘University of British Columbia.’

The interviewer slurs: ‘That where your accent’s from?’

‘My accent?’

‘It just shifted. I have an ear for accents.’

‘Oh. I’m from Colony Two.’

‘Interesting.’

*

William New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. New’s most recent books include Neighbours (2017) and In the Plague Year (2021, reviewed here by Gary Geddes). Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Tamas Dobozy, Rhonda Waterfall, Leah Ranada, John MacLachlan Gray, Bill Stenson, Jack Wang, and Michael Kenyon for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1479 Play time”