1390 Black Canada revisited

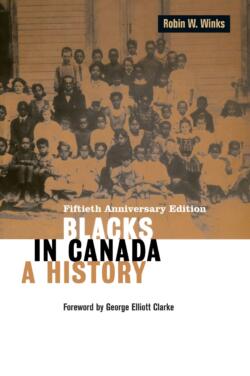

Black Canada: A History. Fiftieth Anniversary Edition

by Robin W. Winks, with a foreword by George Elliott Clarke

Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021 (second edition; first published by McGill-Queen’s University Press and Yale University Press, 1971)

$32.95 / 9780773516328

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Black Canada: What I should have learned in high school

Black Canada: What I should have learned in high school

February is Black History Month, so it was probably a good marketing strategy to re-release this 50-year-old history of Canada’s black people. I had my doubts that it was such a good move republishing a 1971 book by a Yale University professor born in Indiana to white parents. But I had a rethink and concluded that this is an important, if flawed, history that covers a vast amount of information we didn’t learn in school.

I went to high school in a small town in BC where history was served up in small dollops as “social studies,” but I do not remember hearing any mention of black history much less being introduced to a textbook like Winks’s sweeping panorama of events starting in 1628 with the first wave of black migrants.

For example, I did not learn about Father Le Jeune, the Jesuit missionary who baptized the first slave to be sold in New France. “You say by baptism I shall be like you,” the boy said, but “I am black and you are white, I must have my skin taken off to be like you.”

Nor did I know that in the late 1700s Thomas Clarkson became “the true father of abolitionism in Britain.” The parliamentarian William Wilberforce is often given that title, but Winks corrects the record. I had some idea about what Winks called the “Back to Africa” movement from reading Lawrence Hill’s novel The Book of Negroes as an adult, with its detailed account of slaves who chose to leave Nova Scotia to return to Africa. In Winks, I also learned of the politics of colonization.

I recently saw Harriet, the film about slave liberator Harriet Tubman and her successful efforts to use the legendary Underground Railroad to transport American slaves to safety in Canada. I also read Colin Whitehead’s novel The Underground Railroad, which portrays the route to freedom in Canada for many slaves.

But I knew little of the degree of discrimination and racism that greeted many of the newcomers who sought a new life on Canadian soil. I did not fully appreciate the impact of the American Congress’s Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, allowing slave owners to pursue their “property” north of the border.

I learned that Upper Canada (Ontario) was the “first province to take action against slavery.” In spite of it, I heard the story of Chloe Cooley, the slave girl who was “bound” and “spirited across the Niagara River to be sold to Americans.” As Winks notes the Upper Canada law “freed not one slave.” In Lower Canada, Louis-Joseph Papineau, leader of the Rebellions of 1837, called on the House of Assembly to uphold the law allowing slavery and proposed houses of correction for slaves.

I was vaguely aware that there was resistance to slavery in Canada, but knew nothing of the various groups of black immigrants called Maroons, Fugitive Slaves, Black Pioneers, and “Refugee Negroes.” All faced vicious prejudice and bigotry in their new home.

Winks’s short chapter on British Columbia’s black immigrants added new details to my slim knowledge. Encouraged by Vancouver Island governor James Douglas, whose mother was said to be a mulatto or Creole, and with Civil War threatening, many California blacks and others came to Victoria in the gold rush year of 1858.

“Victoria Negroes . . . were literate and skilled, and these skills were in demand,” Winks writes. But it wasn’t long before discrimination led to segregation of churches and schools. They were banned from participation in public discourse. Fear set in when in 1868 “Indians murdered two of the Negro settlers.” More violence was to follow.

Newspapers that first accepted the migrants began to shun them. Amor de Cosmos, later governor, wrote positive editorials in his British Colonist. Then he turned on them, arguing that they had “no principles.” In an 1860 editorial, he or his editor wrote “No wonder the world is so ready to believe that the colored race is unfit for freedom.”

Later in life, I read Abraham Lincoln’s statement about the Civil War not being about freeing the slaves, but I did not know that it “quickened anti-Americanism” in Canada. I don’t recall Frederick Douglass mentioning this aspect of Canada’s response, although his autobiography is a superb slave narrative full of insights.

Winks walks us through five centuries of Blacks in Canada and what he reveals is not a Canada that is the progressive nation we like to think it is. Full chapters deal with black churches, schools, newspapers and self-help groups. Each reveals communities of black people forced to endure the worst conditions in the country they had turned to for help.

But Winks’s attempt to portray this history does not go unchallenged. While publishing a white scholar on black history may have been more acceptable in 1971, after the 1960s Civil Rights movement and before Black Lives Matter, it is far less acceptable now. Today there is a new awareness of black history and there are plenty of black historians, writers and commentators able to chronicle it in their own voice.

Maybe it should be obvious that scholarship has no colour. Regrettably, it does. For example, some scholars argue that the concept of whiteness itself includes a built-in racial prejudice. Others are busy trying to undo black history. The Texas schoolbook publishing industry is apparently revising the history of slavery. Slaves will now be characterized as low-income immigrant workers.

Having Canadian poet George Elliott Clarke, a University of Toronto professor of Canadian literature, write the Foreword goes some way to resolving the problem. He charges Winks with being “pessimistic.” “Hold on!” he tells the historian. “Here is a damning portrait of blatantly stereotypical Black indolence and/or incompetence.” He is referring to Winks’s description of Black Loyalist farmers in Nova Scotia. He notes that Winks accused “them of being poor farmers, but ‘Black people received land . . . on an apartheid-style basis.’” The same holds true in other sectors of the economy where black immigrants struggled to make a living.

In Clarke’s critique of what he calls a “magisterial and authoritative tome,” and a “comprehensive study,” we read that Winks has failed to write a historically and culturally accurate portrayal of blacks. However, Clarke also offers this observation:

Winks’s bleak rendition — dismissive view — of our history has provoked and goaded so many now to check the facts for themselves, reassess them anew, and rewrite them — as social scientists, as poets, as filmmakers, as dancers, as novelists, as screenwriters, as artists and artisans, as composers and librettists.

Winks acknowledged that criticism of some chapters was “just” and that his approach was marked by an insufficient “understanding of Black culture or of economic class realities.” He added that Black Canada is “a depressing story” and that “Negroes in Canada were often responsible for their own plight.” But does the book deserve outright dismissal?

Winks has provided a dated but sincere attempt to teach all Canadians a part of history they did not learn in school. For Black historians today, he has footnoted hundreds, perhaps thousands, of starting points that could be useful in the process of re-interpreting that history. Fifty years on, Black Canada: A History remains a resource that should not be overlooked.

*

Ron Verzuh is a Canadian writer, historian, and documentary filmmaker. His work has appeared in The British Columbia Review since it was founded in 2016 as The Ormsby Review. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada was published in January 2022 by University of Toronto Press. See here for Ron’s essay in The Ormsby Review on Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy and here for Mike Sasges’ review of Ron’s Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Tom Wishart, Janice Baker, & Lynn Campbell, Gregory Betts, Maureen Webb, David Lester, Geoff Mynett, Bonnie Henry, and Bonnie Henry & Lynn Henry. He lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1390 Black Canada revisited”