1379 Bill Hong & the Cariboo Mountains

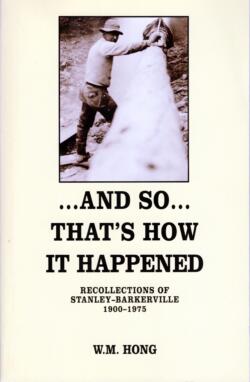

…And So…That’s How it Happened: Recollections of Stanley-Barkerville, 1900-1975

by W.M. (Bill) Hong. Originally edited by J.R.S. Hambly, updated by Gordon Lee, edited by Gary and Eileen Seale

Quesnel: Spartan Printing, 1978; fifth Printing January 2018 by Blueline Graphics, Coquitlam

[price to follow] / 9780987365004

Available at Frog on the Bog Gifts, Wells, BC

Review by May Q. Wong

*

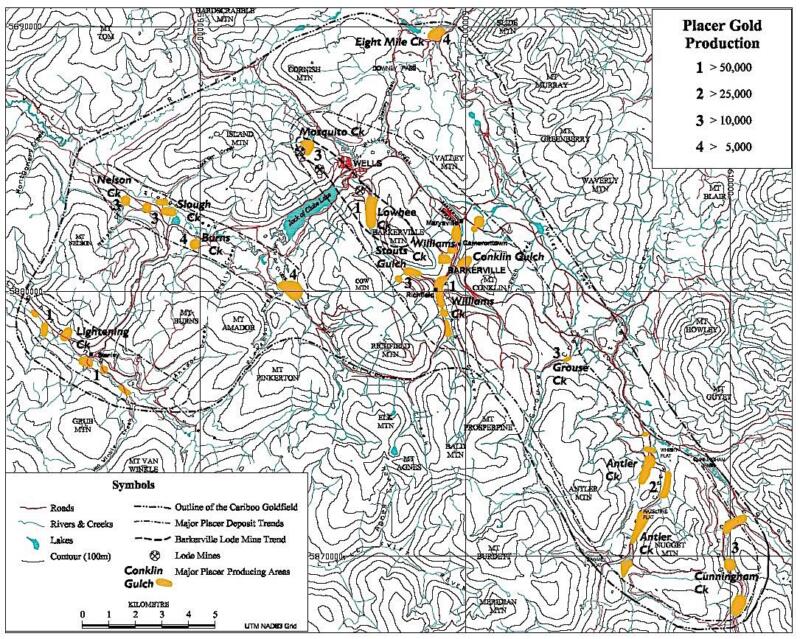

Maybe you have heard of the phrase: “There’s gold in them thar hills….”[1] There was, and according to Bill Hong, still is, in the goldfields of the Cariboo region of British Columbia, when he wrote the story of his family in 1978. In his own words: “There’s a lot of paying ground in B.C. for mining…There’s lots of gold in the Cariboo…All the high runs of gold, only very few have been found” (pp. 23-24).

Maybe you have heard of the phrase: “There’s gold in them thar hills….”[1] There was, and according to Bill Hong, still is, in the goldfields of the Cariboo region of British Columbia, when he wrote the story of his family in 1978. In his own words: “There’s a lot of paying ground in B.C. for mining…There’s lots of gold in the Cariboo…All the high runs of gold, only very few have been found” (pp. 23-24).

Perhaps the possibility of finding some of that gold is what attracts enough people to buy …And So…That’s How it Happened and for the book to be in its fifth printing (2018)! The book will certainly be of interest to historians of the Cariboo goldfields and the pioneer towns of Barkerville, Stanley, and Wells. There are details of wages, the cost of goods and gold, the yield of various sites, and descriptions of pioneer living such as how milk, fresh beef, power, mail, or telephone service were delivered. The information about different kinds of mining and in particular, hydraulic mining is fascinating, even if the impact was environmentally devastating. This type of mining involved the use of high-pressure jets of water — and enormous quantities of it — to dislodge, literally, mountains of soil and rock. The resulting slurry was channeled into sluice boxes where the heavier gold remained after the rocks and soil were washed away. The photo on the front cover shows Bill Hong operating a “monitor,” the large water canon, while the back cover shows him holding a gold pan.

This book is also an invaluable resource and reference to people interested in Chinese history in the Cariboo. While perhaps short on detail, the list of names and numbers of photographs makes it an important record of pioneers whose stories have rarely been included in mainstream history. Bill Hong was well-connected in the Chinese Cariboo community, and of course he recorded stories about non-Chinese miners such as the mysterious disappearance of his former partner Jack Hind, considered “…one of the most famous unsolved mysteries of the later days of the Cariboo goldfields” (p. 58), or of his friend Frank Kibbee, “…the main character in one of the most gruesome ‘bear stories’ in the annals of the Cariboo” (pp. 236-240).

Bill Hong met with the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, the Governor General of Canada, and the Introduction of his book was written by P.J. Mulcahy, a former Deputy Minister of B.C. Department of Mines. Bill has been noted among the list of the “strong and interesting characters” of the Cariboo gold rush in Atholl Sutherland Brown and Chris H. Ash, “The History and Geology of the Cariboo Goldfield, Barkerville and Wells, BC.” They write that:

Four of the most memorable include: include: Billy Barker, an early placer miner [for whom Barkerville was named]; Bill Hong, a later Chinese placer miner; Amos Bowman, the first geologist; and Fred Wells, a prospector and mining entrepreneur during the heyday of lode mining.[2]

Born in Stanley, British Columbia, in 1901, Bill Hong,[3] a self-described “hydraulic man,” followed his father’s footsteps as a placer gold miner and businessman. After he retired in 1978, he wrote his family history in longhand, and these recollections form the opening chapter in the book. The prose reads more like unedited journal entries, yet it feels like the reader is having a conversation with the author.

Bill Hong’s father, Won Gar Wong (born 1852), and two older uncles left their home in Kwangtung Province, China, to find their fortunes in Silver City, Nevada, in 1862. His father decided to try gold mining in Canada in 1880, and arrived in Stanley after walking 1,200 kilometres in forty-five days from New Westminster. As a measure of his business acumen, after about a year of gold mining, he bought the Kwong Lung Kee Groceries Store in Stanley, and by 1885, had saved enough money to go back to China to marry. On his way back to Canada, he bought thousands of dollars of supplies that he shipped from Hong Kong to the store in Stanley, via Victoria and Yale. In 1910, Won Gar Wong brought his wife and family, including Bill (the eldest) and Bill’s four siblings, back to China so the children could get a traditional Chinese education. Bill’s mother became ill and died in China. In 1912, Won Gar Wong re-married and Bill (11 years old) joined the couple to return to Canada.

Bill stayed in Victoria to attend school until 1915 before returning to live in Stanley. After only a few more years of education at the school in Barkerville, he was required help out on his father’s mining claims. To make ends meet during mining downtimes, Bill chopped and sold firewood, worked on the Grand Trunk Railway in Prince George, and built airplanes for Boeing in Vancouver. Over his fifty-year career in mining, he dug ditches, built and rebuilt trestles with flumes for water to cross roads and gulches, erected dams to divert water from lakes, operated drills and monitors (water hoses), worked for large mining companies and hired his own teams to work on his personal claims. His businesses included owning and operating stores and a café in Barkerville, Stanley, and Wells; owning two trucks with public service licences; and holding a partnership in a Barkerville power company. He also gave back to his community as an active member of what became the Barkerville Historic Site in 1958, serving as its Fire Chief in the 1940s and 50s.

He married his wife Fay in the summer of 1923. They raised five children, three sons, Pat, Ray, and Louie, who together ran their dad’s Deluxe General Store in Wells; and two daughters, May and Lil. None of his children went into mining.

Bill Hong also recorded stories — as oral history — about the people and companies and their mining activities in the Cariboo. The recordings were transcribed and edited and with editors’ notes comprise the rest of the book, accompanied by many photographs. The photos provide an important and fascinating record of hydraulic mining and the people, including some women and children, who were part of these pioneer Cariboo mining communities.

Significantly, many of the stories and some of the photos concern the Chinese miners who worked in the region as well as business owners and the communities of Stanley and Barkerville. Brown and Ash also wrote:

Placer miners were, initially, dominantly Caucasian, and most were British subjects, contrary to what might be expected, as they had come north from California. As production became less rewarding, Chinese miners progressively became more numerous … [it has been] estimated that in 1875 Caucasians constituted 55 percent of the miners but by 1880, Bowman (1886) reported that 80 percent of the miners were Chinese…. They were prepared to work for less pay and they were secretive and careful with the gold they found. The objective of most was to accumulate enough gold to return to their families and villages in China as relatively wealthy men. They worked hard to do so.

Readers might already be aware that Barkerville, since 1958 a well-recognized tourist attraction with fully reconstructed buildings, had a large Chinese community with its own Chinatown. The Chinese did not only own businesses in Chinatown but also operated a number of stores in the main part of town, including several general stores, a butcher, two Chinese laundries, and even a baker specializing in Chinese buns and noodles. One of the general stores, “Kwong Lee (referred to as the Chinese Hudson’s Bay Company) … owned by Loo Gee Wing (p. 183)” was a major commercial presence not only in Barkerville, but also in Victoria and other boom towns. There was also a separate Chinese cemetery, where the dead were temporarily buried for a number of years before their bones were collected, securely identified and packaged, and sent, via Victoria, back to China for a “proper” burial and a more permanent resting place. Hong devotes Chapter Five to Chinese burial traditions.

Stories about Chinese individuals are scattered throughout the book, but Chapter Four concentrates on stories about the Chinese in and around Bill Hong’s birthplace of Stanley. It also had a Chinatown, where the miners, who worked at various mining sites around the area, could occasionally gather among their countrymen, buy supplies, have a meal, and gamble. With a sentence or a few paragraphs and perhaps a photo, Hong has immortalized the Chinese individuals, whose names might otherwise have been lost. Names of men who stayed only for a short time before moving on to other work, other locations, or even back to China, have also been included. The following story, concerning an old-timer and the Chinese woman who was his partner, gives a flavour of the book’s contents:

Around 1868, Wong Man Ding, nicknamed “Cariboo Jack” [see photo on page 62], walked from Yale up the Cariboo Road to 150 Mile House, on to Quesnel Forks, Keithley Creek, and over the Mountains to the head of the Swift River and Stanley. He prospected and worked at placer mines all his life — at Davis Creek, Dunbar Flats, and other locations. He also cut cordwood for the boilers of The Eleven of England [one of the first mining companies in Stanley which began operations in 1876]. In 50 years, Cariboo Jack only left the Stanley area once, spending a winter in Prince George. He lived with a sporting girl named None Gau, but better known as “Old Potatoes.” She died just a few months before Jack left for China. Hers is the only Chinese grave in the Stanley cemetery. In 1928, a donation from the Chinese community enabled Cariboo Jack to return to his homeland where he died two years later (pp. 60-61).

Similarly the Chinese miner Wong Ying Fook, who left an ingenious legacy that lasted for almost fifty years:

This trestle [photo on p. 106] built by Wong Ying Fook, crossed Devil’s Canyon and carried water from the canyon and Burns Creek to Slough Creek Mine’s first bench of hydraulic claims. Fook constructed this trestle in the mid 1870s (before the wagon road — Cariboo Highway — came through the canyon). The largest timber in the structure was no more than eight inches in diameter. The flume was three feet high and a foot wide; the trestle, which averaged 52 feet in height, was 250 to 300 feet long. In that three decked trestle, there was not one nail or steel drift-pin — only wooden pins were used, one inch to two inch. In 1905, Ng Yam replaced some post stringers and braces, but the trestle was not dismantled until 1920-21, when its rotting condition represented a hazard to the highway traffic beneath. “It was a wonderful piece of work” (p. 106).

On my first reading of the book, I admit I wasn’t very impressed with the writing style or even the contents. There were many mining terms I didn’t understand, which was frustrating. But the more I reflected and wrote about this book, the more it grew on me as I began to understand its significance as an invaluable historical resource. The editors made it clear that the information presented had been faithfully transcribed from audio recordings, and like Bill Hong himself, there are no literary pretensions. And as he was wont to say, after sharing a story or two, “…and so…that’s how it happened.”

*

May Q Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. A graduate of McGill University, she holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has recently reviewed books by Joanna Chiu, Ben Maure, Bernard A.O. Binns & Ron Smith, Patrick Saint-Paul, Ian Greene & Peter McCormick, Beverley McLachlin, Graeme Taylor, Dukesang Wong, and Henry Yu.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Attributed to Matthew Fleming Stephenson (1802–1882), an American miner, geologist, and mineralogist. And made famous in Mark Twain’s 1892 novel, The American Claimant.

[2] The article includes maps that are very helpful to the reader to orient them to locations mentioned in the book and to understand distances.

[3] “It is interesting to note that Bill Hong’s name was originally “Wong Mon Hong” with — as is Chinese custom — the surname first. The original surname was dropped when someone noticed that the initials of the first two words in “Wong Mon Hong” formed the abbreviation for William. Soon, Wong Mon Hong was W.M. “Bill” Hong, a change that was later legally recorded. The three sons also adopted the surname Hong, although their sisters remained Wong until their marriages.” From “Editor’s Note,” p. 25.

3 comments on “1379 Bill Hong & the Cariboo Mountains”

Thank you for reviewing this beloved book.

My Mom, Eileen Seale, Quesnel, BC, and her husband Gary (deceased) edited this book. My cousin passed along your review to me and I shared it with Mom. She was delighted. She will pass the review along to Bill’s family.

I grew up knowing Bill as Grandpa Hong, and spent time with him and my Mom over his kitchen table in Wells, BC, as Mom took notes for his book. We drank good tea and had many laughs. We loved him and Mrs. Hong (my Grandma and she were very close friends as my Grandma spoke Chinese).

We are also in touch with Bill’s great granddaughter and great grandson (whom my brother and I grew up with).

Anyways, my Mom said she would be happy to hear from you if you have the time. She has such fond memories of Bill and a keen memory of there times together.

Thank you kindly.