1464 Chinatown settlers and letters

Occupying Chinatown

by Paul Wong

Vancouver: On Main Gallery, 2021

$80.00 / 9780969477778

Reviewed by May Q Wong

*

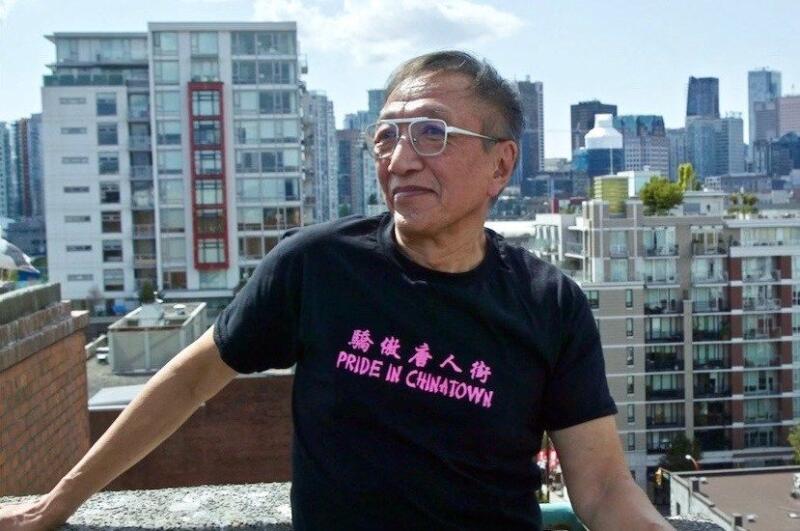

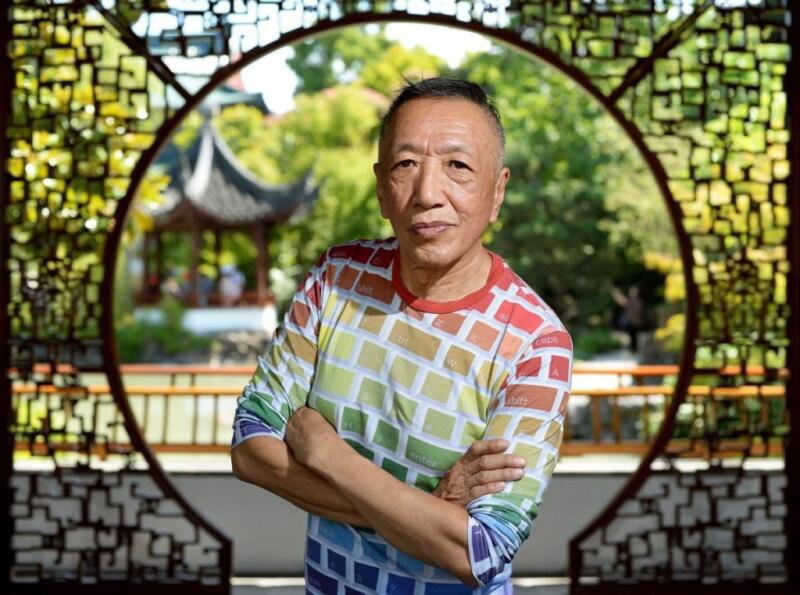

In this limited-edition clothbound book, the reader will share a personal journey with world-renowned artist Paul Wong, who pays homage to his mother and family, and by extension, the early Chinese immigrants who established Vancouver’s Chinatown. It is a partial record of his year-long residency, from March 2018-March 2019, at Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden, located in the heart of historic Chinatown. During that time, Wong created a number of multidisciplinary artworks which were displayed in-house and/or installed around the broader community. He also hosted collaborative performances, workshops, and consultations, all of which were video recorded and can be viewed on his website.

In this limited-edition clothbound book, the reader will share a personal journey with world-renowned artist Paul Wong, who pays homage to his mother and family, and by extension, the early Chinese immigrants who established Vancouver’s Chinatown. It is a partial record of his year-long residency, from March 2018-March 2019, at Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden, located in the heart of historic Chinatown. During that time, Wong created a number of multidisciplinary artworks which were displayed in-house and/or installed around the broader community. He also hosted collaborative performances, workshops, and consultations, all of which were video recorded and can be viewed on his website.

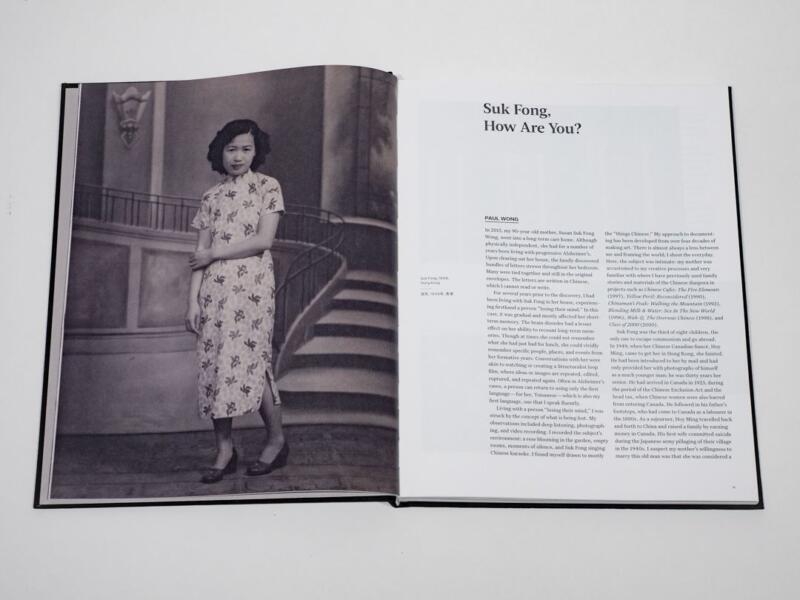

The book is divided into three sections, each introduced by essays that move from the intimate, to shared personal, to public perspectives. In the first section, Paul Wong’s essay, Enter, introduces the reader to his mother, Susan Suk Fong Wong, who came from China to Prince Rupert in 1950 with her new sojourner husband, Hoy Ming. They had four children, of whom Paul was the youngest. Readers are not told much about Hoy Ming, other than that he arrived in Canada in 1923, following in his own father’s footsteps, and would have paid the $500 Chinese head tax. This was his second marriage; his first wife committed suicide during the Japanese invasion of China. He died in 1968.

About ten years after their marriage, Suk Fong took the children to Vancouver, while Hoy Ming continued to work in Prince Rupert. While raising four children as a single parent, she ran a corner grocery store and later worked as a waitress.

In her latter years, Paul lived with her and watched as her mind slowly deteriorated from Alzheimer’s disease.

Living with a person “losing their mind,” I was struck by the concept of what was being lost. My observations included deep listening, photographing, and video recording. …I found myself drawn to mostly the “things Chinese.” My approach to documenting has been developed from over four decades of making art. There is almost always a lens between me and framing the world: I shoot the everyday. Here, the subject was intimate: my mother was accustomed to my creative processes, and very familiar with where I have previously used family stories and materials of the Chinese Diaspora in [other] projects…. (p. 11).

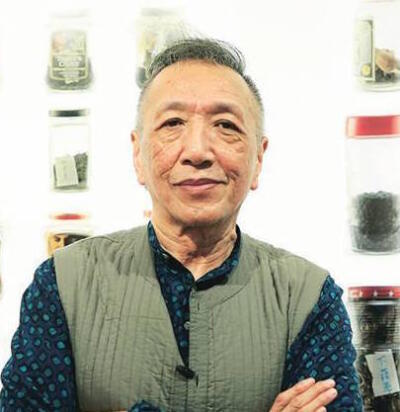

His video recording of their conversation as they perused the contents of her kitchen cupboard is an intimate peek into a son’s attempt at capturing traditional knowledge and a fading way of life. Suk Fong, like so many Chinese women of that era, was a healer who used Chinese herbs and foods to create medicine, tonics, and soups for everyday living. In the video, Mother’s Cupboard, Paul pays homage to her expertise, but as he asks about each bottle of ingredients, we can sometimes hear her impatience – or is it concern – that he does not already know these things.

Wong later photographed each jar individually, organized them by bottle shapes, and reproduced their pictures onto posters which were featured at forty-five bus shelters across Vancouver. The bottles were also displayed as an in-house installation. They were a thought-provoking juxtaposition: recognizable brand-name recycled bottles containing unfamiliar exotic (some banned), rare, and expensive traditional Chinese medicinal herbs and tonics.

Wong’s art provokes an emotion, a reaction, or a question in the viewer. Some of the jars, such as those holding sharks’ fins, or snake tonics could be disconcerting. Might they even evoke indignation or disgust? Personally, having been raised in the same era, by a mother who had similar knowledge, I was nostalgic as I looked at the pictures and wistful as I listened to the language of my childhood.

In 1982, Paul accompanied his mother on her first visit back to China to visit her family. The video, Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade, records the visits to their ancestral village, and conversations with various relatives. It might also include snippets of return visits to China. Viewers of the stills in the book or watching the video might be dismayed by the constant cacophony in the streets; the primitive farming and living conditions in rural China, and; the paucity of goods at the market. Between grossly lingering scenes of a peeing pig or a farmer slogging through a flooded field behind a water buffalo that has just defecated, Wong shows an older woman stand tall and proud to be filmed, or children playing exuberantly in front of the camcorder.

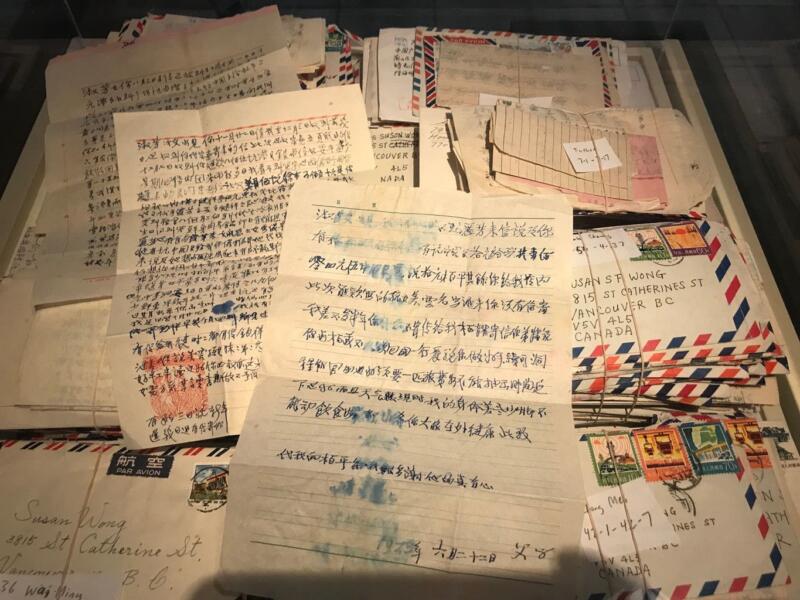

When Suk Fong moved into a care facility in 2015, the family found 900 letters sent to her from China, between the 1950s to the mid 2010s. The second, and longest section of the book, Family Matters, focusses on 20 of those letters, written by her father, siblings, and a niece. This section is prefaced by an essay written by Christopher Lee, Associate Professor and Director of the Asian Canadian and Asian Migration Studies Program at the University of British Columbia. He and a number of his students read and translated the letters into English. Entitled Reading Letters, Reading with Trust, it is about their process as well as and the reactions of the readers to the letters and to the writers themselves:

There is something powerful about seeing the mark of a pen, a smudge of ink, the turn of a phrase, all hints of a personality whose absence could be viscerally felt….I realized that these intuitive responses needed to be unpacked further….(p. 45).

It is one thing to read letters and diaries of strangers long dead, but Lee and his group of Chinese Canadian students were delving into the private thoughts, anguish, and aspirations of some people who were still alive, and who was related to someone they were working with. As they processed the materials, Lee wrote: “we became more and more aware of our fraught, even voyeuristic relationship to the letters in front of us…. [each grappling with] how to read in a responsible and caring way the letters [Suk Fong] collected and left behind” (pp. 46-47).

In this section, we learn about the daily lives of those left behind in Communist China. Suk Fong’s father was a businessman and landowner, whose family lived in a large, ornate compound. As such, he and his family were considered “bad influences” requiring “re-education” by the Communist regime. What happened to him was a brutal example of the violent and prolonged persecution imposed on thousands of people behind the Bamboo Curtain. Everything was stripped away and the family was scattered. He started writing to Suk Fong only after being released from incarceration, decades later. His letters were reproduced as large wall hangings with photos and the translations superimposed onto the writing. He was eventually reunited with his children, and died in 1973.

A number of the letters from Suk Fong’s siblings are about their father’s death and burial. We also hear about their difficulties as children of a disgraced father. The longest letter, written by Suk Fong’s niece, Snow, is a heartbreaking tome of abandonment, persecution, betrayal, and hardship. The thirteen-page letter was replicated and displayed as a scroll.

The letters all showed how much the family looked to Suk Fong for help: financial, goods, or her assistance to get them to Canada. She seemed to have fulfilled some of their wishes, despite being a single mother and small business owner in a foreign country with racist attitudes against Chinese. They still held the belief that life was easier and more prosperous in the West – after all, it wasn’t called Gold Mountain for nothing – and didn’t consider that Suk Fong faced her own hardships. But she, like so many immigrants, held the responsibility, and burden, of one who has “escaped” a troubled homeland.

The third section is introduced by the essay: “Private to Public: A New Collective Experience of Chinatown,” by Debbie Cheung, Marketing and Communications Manager at Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Gardens, associate editor and co-designer of the book. Cheung highlights some of the major projects undertaken by Wong during his residency and comments on how the artist transformed private things, like letters, into public art.

The beginning of Wong’s residency coincided with the City of Vancouver’s formal apology to Chinese Canadians for past racist policies. Cheung also remarks on how Wong’s use of the public space that was Chinatown, to engage the community on issues of identity, belonging, and justice. One example is the two Saltwater City Vancouver signs in Chinese characters that Wong created. In one version the characters are written on a wooden board and hung above a gate opening into the Sun Yat-Sen Classical Gardens. Cheung writes:

The artwork is titled after the name given to the city by the early Chinese settlers, recalling the heydays of Chinatown when the streets were filled with colourful signs. Suk Fong’s fellow Cantonese and Toisanese migrants would have pronounced the characters… as “Haam Sui Fow Won Goh Wah”, a vernacular term…. The reference to saltwater as overseas is unique to Cantonese culture, thus when Wong reiterates the characters in the form of a sign, he is reclaiming a physical space for the language of his mother’s generation (p. 151).

Another version was made into a pink neon sign which was permanently installed as a public art piece after an extended public consultation.

…the back alley of 475 Main Street was chosen as Salt Water City Vancouver’s final home. This seemingly unremarkable location was once home to Vancouver City Hall from 1889 to 1929. Today, it is where the invisible members of society reside.… The neon is like a radiant source of strength amid chaos – a metaphor that the early Chinese settlers could identify with as they adjusted to life in a foreign country. The selection of 475 Main Street, therefore, is both a symbolic and an unconventional choice for the publicly funded art piece. Saltwater City Vancouver thus encourages visitors to explore every overlooked corner of Chinatown to find the traditions and stories hidden within (p. 152).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, vandalism and racist violence increased in Chinatown, so I wonder how many visitors will actually seek out this sign, so far from the beaten path. This book is a valuable alternative to experiencing the artwork in person.

Full disclosure: I am not an art critic, and even though I have lived in British Columbia for over forty years, I had not heard about Paul Wong or his art. But some of my own family history parallels that of Paul’s family: we share the same last name; my family came from neighbouring Hoyping county in Guangdong, so I speak a similar dialect; my father arrived in Canada in 1921 and paid the head tax; my mother corresponded with my older sister and other relatives in Hong Kong and China; and having visited China in 1966 with my mother, I am familiar with the need to bring back goods. My parents also referred to Vancouver as “Haam Sui Fow.” So the materials in the first two parts of the book most resonated with me and I am grateful to have been introduced to Paul through Occupying Chinatown and to share some common ground.

*

May Q Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. A graduate of McGill University, she holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (TouchWood, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. Her second book, City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has recently reviewed books by W.M. (Bill) Hong, Joanna Chiu, Ben Maure, Bernard A.O. Binns & Ron Smith, Patrick Saint-Paul, Ian Greene & Peter McCormick, and Beverley McLachlin.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster