1362 Seamstress to cabinet minister

A Liberal-Labour Lady: The Times and Life of Mary Ellen Spear Smith

by Veronica Strong-Boag

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021

$89.95 / 9780774867245

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Who?

Who?

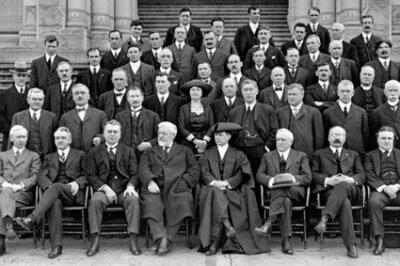

Mary Ellen Spear Smith (1863-1933) was British Columbia’s first female Member of the Legislative Assembly. She was also the first female cabinet minister and the first female speaker of an Assembly anywhere in the British Empire and Commonwealth.

“Times and Life” reads the subtitle, not “Life and Times.” Our heroine appears to have left no early photos, letters or intimate diaries, no confession of innermost thoughts or feelings. She did leave a commanding public image, against a backdrop of Canadian political life in the early 20th century, and a record of accomplishments deserving recognition. As an acclaimed scholarly chronicler of Canadian, especially British Columbian, herstory, Veronica Strong-Boag is determined that Mary Ellen Spear Smith will not slip from recorded memory. In the absence of personal papers, the author acknowledges her reliance on newspapers and magazines and their increasing availability in digitized format.

Strong-Boag acknowledges also the “scholarly and activist cultures of redress and fair dealing that emerged in Canada and globally in the half century after the 1960s” demanding “a reckoning with history”. In this light, especially when looking at race and ethnicity, Mary Ellen Spear Smith appears as “flawed” but she was also “extraordinary”, and her biography must be “neither canonization nor condemnation.”

Mary Ellen Spear was a working class immigrant with relatively little formal education, a coal miner’s daughter, born in Cornwall. Her family moved first to Plymouth, Devon, then to Northumberland. Strong-Boag evokes the atmosphere and life in a British mining village of 1881, where the census records Mary Ellen as a teenage seamstress living with her parents. Two years later she married Ralph Smith, a widower with a daughter, and entered the milieu in which women, no matter what their talents, “measured themselves by their public reputation for excellent housewifery.” Three children came in rapid succession, a fourth after their move to Canada. Strong-Boag helps our understanding of the traditions and movements which shaped the Smiths’ ideals. Primitive Methodism stressed self-help, education, self-improvement, temperance, sobriety and discipline. Mary Ellen learned early to project the public image of a “Maternal Feminist.” She and Ralph were interested in the co-operative movement, followed the careers of prominent Whig reformers and participated in the emergence of a political creature known as a “Liberal-Labourite.”

Suffering from respiratory problems, Ralph needed to work above ground, but he still worked for the mines. Mary Ellen’s parents had settled in Nanaimo, British Columbia. In September 1892 Ralph and Mary Ellen joined them in the uplifting enterprise of “replenishing the Empire” and the scene shifts to the New World.

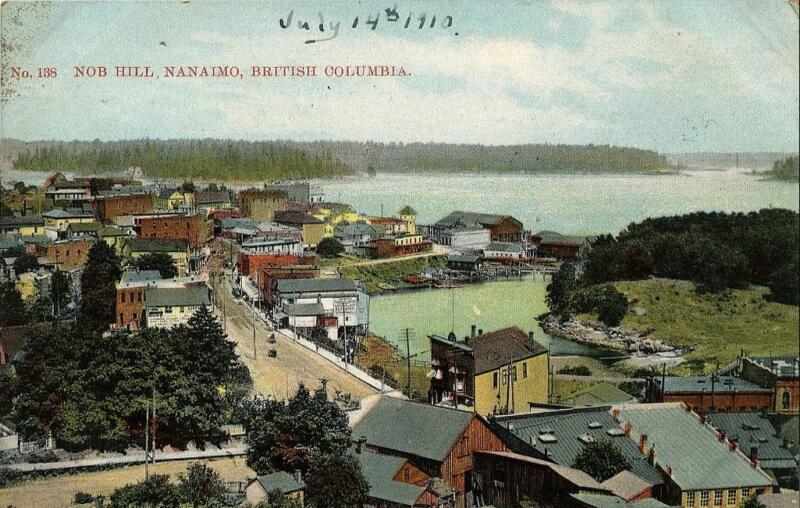

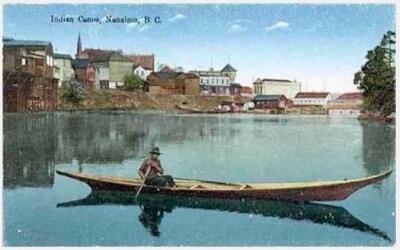

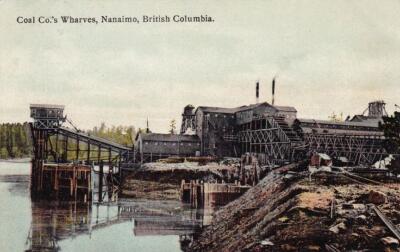

At the turn of the 19th-20th centuries Nanaimo was “Canada’s Newcastle of the Far West,” dominated by the coal industry. When they looked beyond the waterfront, Newcastle Island reminded newcomers of home, and as first president of the Tyneside society, Ralph treasured the reminder. Recently we have been asked to call the island by its older, Indigenous name, Saysutshun. It seems as if erasure upon erasure can only blur the town’s history, but the Nanaimo Museum continues to feature a miner’s cottage, along with a slice of the city’s old Chinatown and an extensive Snunéymuxw exhibit, while nearby the Hudson’s Bay Bastion looks across the strait to the island. Downtown a miner’s lamp holds the perpetual light beside the sanctuary of St. Paul’s Church in which every service begins with a commitment to work together “in a spirit of reconciliation as we worship and serve on the traditional lands of the Snunéymuxw First Nation.” But the learning curve has been steep: “Like most contemporaries, the Smiths believed that racial hierarchy was naturally or divinely ordained, an assumption reinforced by much scholarship of the day.” White settlers despised and even feared Asians; they scarcely noticed the Indigenous people. To her credit as a historian, and without belabouring the point, Strong-Boag manages to covey her disapproval of these Settler attitudes without necessarily disapproving of the Settlers.

The Smith family lived at 171 Machleary, Mary Ellen’s parents at 20 Milton. Ralph worked for the New Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company [NVCMLC], the rival of James Dunsmuir’s Canadian Collieries. Their story unfolds within a time of emerging labour and feminist activity, sometimes but not always aligned. Continuing the community activism begun in Britain, Ralph and Mary Ellen held to policies of political gradualism and sometimes competing causes. They supported unions, female suffrage, and Chinese exclusion. They wanted a fair deal — but for favoured peoples.

Soon Mary Ellen was acquiring organizational experience with such bodies as the WCTU and the YMCA, reciting at benefit concerts and taking leadership in various Ladies’ Committees for civic improvements, hospitals and public health: “volunteer efforts for the city hospital confirmed Mary Ellen’s credentials as a worthy partner for an ambitious representative of BC workers.” They envisioned – “a partnership between White women and workers in the humanization of capitalism and the assault on patriarchy.” Mary Ellen was a gifted entertainer and speaker, physically attractive with a melodic voice, quick wit and charm.

Strong-Boag’s narrative of Ralph Smith’s political career is fascinating for what it says about municipal, provincial and federal politics then and now and for how familiar it all sounds. In 1900, as the MLA candidate for the Independent Labour Party, Ralph demanded the eight-hour working day, the union label on manufactured items, public ownership of utilities, and Chinese exclusion. But in a Liberal government, he learned the art of the possible. He also learned that political success — Labour or Liberal — led to increased social success, which in turn led to loss of support from organised labour. A paradox still to be resolved. Strong-Boag several times refers to him and Mary Ellen as a “power couple”, and she was with him every step of the way with her gentle voice and amusing speeches, not to mention her genius as a hostess, projecting “a reassuring femininity to partner Ralph’s collier masculinity”. He became increasingly associated with provincial business and financial interests, but both were determined that capitalism could be called to account and made to work for all citizens.

Mary Ellen was a vital part of Liberal success on the west coast, but how would she and Ralph fare in Ottawa, beginning “as sojourners with limited income and few social connections who came from a region regarded as both remote and eccentric ” — a reputation Vancouver Island still proudly maintains? As it turned out, Mary Ellen did just fine. Her early skills as a seamstress enabled her to “dress to impress” on a modest budget, and her passion for music endeared her to Zoe Laurier, wife of the Prime Minister. The Smiths succumbed to Sir Wilfrid’s Old World charm (although he was born in rural Quebec), and the “sunny ways” appropriated by his most recent successor.

During his first term as MP, Ralph struggled to promote Labour causes, advocating collaboration rather than revolution, but achieved little. He disagreed with Laurier on female suffrage. By the 1904 election he had given up trying to be a Labour candidate, and ran as an unrepentant partisan Liberal.

Mary Ellen perceived that in Ottawa style was as significant as substance, and that operating in a patriarchal and class society required deception and camouflage, tools she learned to use in promoting causes she cared about. Unlike most other parliamentary wives, she continued to endorse both the franchise for women and the ideals of the WCTU. She was often invited to give keynotes at suffrage gatherings. Strong-Boag provides a summary of her speeches and writings, impressive for their style, cogent arguments and awareness of global movements and achievements.

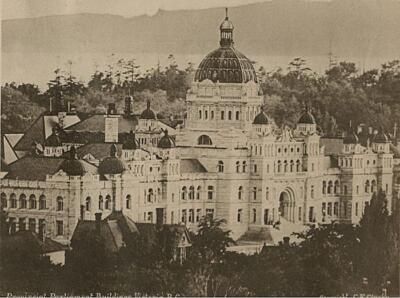

The 1911 election, for reasons which belong in history but not in this review, was a defeat for Ralph and most of the rest of the federal Liberal Party. Returning to the West Coast, the Smiths moved their home base from Nanaimo to the wider stage of Vancouver. Ralph directed his energies to business ventures, to the British Columbia Liberal Party, and after the 1916 provincial election to his Cabinet position as Minister of Finance. Mary Ellen joined the IODE, the Women’s Canadian Club, the Pioneer Political Equality League and any other group from which she could champion her causes.

One association she did not join was the University Women’s Club, which was by definition restricted to women with a post-secondary degree. It may be natural that Mary Ellen resented this exclusion; it is less clear why the author shares the resentment. Then as now, members of the UWC use their academic skills and contacts to achieve many of the same goals dear to Mary Ellen, specifically the promotion of education, rights and opportunities for women. Strong-Boag derides what she calls the “pretensions” and “snobbery” of the UWC which she puts in “stark contrast” to the vision of Helen Gregory McGill and Laura Marshall Jamieson. But both were early members of the UWC, as Strong-Boag well knows, having written a biography of Jamieson, reviewed by Patricia Roy for The Ormsby Review. Strong-Boag is particularly hard on Evlyn Farris, founding president of the Vancouver Club and wife of an influential lawyer who became a Liberal Attorney-General of BC. I encountered this problem with poor Evlyn and her “womanising spouse” when I reviewed Lara Campbell’s A Great Revolutionary Wave, a volume in an important series edited by Strong-Boag.

Mary Ellen continued to attempt linkages across party and doctrinal differences, and was interested in women’s groups acting as auxiliaries to male trade unions. She was a founder of the Voters Education League which denounced the party system. In support of the 1916 provincial referendum on women’s suffrage she toured BC in a Model T Ford along with future Conservative MP Leon Ladner who identified as a suffragist. In 1912, advocating for female wage-labourers, she declared: “everything depends on what we do for the masses; with them we rise or fall.” I confess to some wondering about these “masses”, and who they might be. This former seamstress from a coal-mining family evidently felt she was not one of them. Does anyone admit to being one of the masses? Later in the book Strong-Boag quotes none other than Margaret Ormsby herself as calling the 1924 election “a revolt by the masses against the caucus system, against machine politics and against the spoils system.” So I guess it’s all right.

Ralph spoke strongly on progressive issues: “the Liberal party can only live where it stands and fights for radical principles. If the Liberal party in this province is as radical as it should be there will be no use for a Socialist party.” But he joined Conservative MP H.H. Stevens in denouncing the Komagata Maru migrants as “a moral and public health threat”. The Great War brought new issues and changes of emphasis and growing global industrial unrest. Then he died, in 1917, and Mary Ellen stood on her own as an “Independent Liberal Lady.”

She continued to have difficulty with strict party lines, but endorsed Laurier. She favoured conscription, but not quite in the usual sense; she wanted “the conscription of man-power, the conscription of wealth and the conscription of woman-power”.

Officially entering politics, she ran in the 1918 by-election, quickly realising that Premier Brewster, like most of his colleagues of whatever party “wanted female support without having to sacrifice male candidates or domination of policy.” Newly enfranchised women were expected to “serve as effective handmaidens to male politicians.” She faced a dizzying array of opposing groups, views and activists, and the suggestion that a war veteran might be an even more deserving candidate than a woman.

Having won the by-election she set about the next four years pushing her reform agenda, juggling accommodation and resistance to the party line, pleading for mutual understanding between sexes and classes. She defied stereotypes by using them. During sessions of the legislature, she knitted socks to raise money for patriotic societies, a more useful activity than the male members’ habit of going out for a smoke. She did not wear a hat in the legislature, and made known her preferences for the label “woman” rather than “lady” and “Mary Ellen Smith” instead of “Mrs Ralph Smith.” She was not beyond “buttering up the boys” even as she challenged the male dominance and asserted a “female version of political life.”

Strong-Boag gleans insights into Mary Ellen’s thinking from columns written for the Vancouver Sun, touching on her favourite themes such as capital/labour partnerships, a new world order, eugenics, federal/ provincial jurisdiction, and equal pay for equal work. On January 23 1919, she denounced the poor pay and long hours allotted to nurses, at a time when their value was highlighted by the flu pandemic. Once again, everything old is new again.

Among her writings was a movie script which she apparently submitted to Hollywood movie producers in 1920: “the story opened with the dismissal of women munitions workers from an iron and steel plant immediately after the armistice and closed with cooperation and a pretty love story.” We can only lament the manuscript’s loss.

After her election triumph, Mary Ellen’s political career went, as the chapter heading suggests, “from hope to disillusion.” As one woman within a male system, she was bound to disappoint herself and others, bearing the weight of unrealized expectations and an unfinished feminist agenda. The Cabinet position of Minister without Portfolio was grudgingly bestowed and virtually powerless, except for its signalling that a woman could be appointed to a cabinet in Canada. It was not only her promotion of progressive and feminist causes which brought her into conflict with premier Oliver and the rest of his cabinet. Her resignation from cabinet in November 1921 was widely seen as “a protest from the womanhood of British Columbia against wrongdoing.” Her disillusionment extended to federal politics and well as provincial. Her victory in the 1924 election was a narrow one; a Liberal campaign pamphlet referred to her as “the mothering MLA.” In the post-suffrage Liberal party her role became increasingly “ceremonial.” Her appointment as a one-day replacement for the Legislature Speaker was again more significant as a precedent than as a substantive posting. Beyond her championing of causes aimed at women and children, she was seen as defending more reactionary positions such as Settler entitlement, and the flogging of drug dealers.

Mary Ellen’s defeat in the 1928 election comes a relief to the reader. The details of the election tactics, with plenty of fake news, and the opposition seizing credit for policies and legislation she had initiated, makes for fascinating if distasteful reading. She seems about to slide into restful obscurity, more concerned with family affairs and her financial problems, which were considerable, as stipends and pensions were woefully inadequate.

But of course that was not her way, or Strong-Boag might not have bothered to rescue her for posterity. Mary Ellen refused to stand aside. As president of the provincial Liberal Party she could still make “discreet waves” and, with her adroit handling of egos, “mother the boys into better behaviour”. She also continued active in the federal Liberal organisation. She was not, as hoped and even expected, appointed to the Senate. However in 1929 she was Canadian representative to the League of Nations International Labour Organization, refusing to be quietly token and, while in London and Geneva, earning criticism at home for her “partisan” speeches and admiration for the British Labour Party. She still led protests on cutbacks to progressive legislation, but as the Depression deepened she seemed to lose confidence in democracy, swerving to the political right, flirting with the Social Credit movement and calling for “planned prosperity.”

When Mary Ellen died in 1933, her estate was valued at only $630. Her Honorary pallbearers included leaders of all political parties, but no one from the Labour movement. Representatives of women’s organizations attended in force, and the Vancouver Sun eulogised her as one “who proved in a practical way that the claims of the suffragettes were founded upon good sense rather than emotions alone.”

Strong-Boag concludes with a clear-eyed summary of the legacy of Mary Ellen Spear Smith:

Mary Ellen’s devotion to settler aspirations and prejudices, liberal-labour politics, British imperialism, New Liberalism, and White first-wave feminism opened doors for the talent and industry of some women and men, even as it denied opportunity to others. That challenging legacy stands at the heart of the Anglocentric world that was and sometimes remains British Columbia and Canada …. Disdaining the fragility, self-absorption, and dependence associated with the decorative lady, Mary Ellen, like many suffragists, claimed strength, courage and independence as her inheritance.

Finally, the author, who does not hide where her own ideology differs from that of her subject, asks that Mary Ellen “not be reduced to her undeniable prejudices. Most contemporaries never matched even her flawed vision.”

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is the author of The history of the University Women’s Club of Vancouver, 1907-1982 (Vancouver: University Women’s Club of Vancouver, 1982). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has recently reviewed books by Ian Hanomansing, PJ Patten, Marion McKinnon Crook, Daphne Marlatt, Ayesha Chaudhry, Sylvia Olsen, P.K. Page, and Peggy Lynn Kelly & Carole Gerson.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1362 Seamstress to cabinet minister”