1361 A cabal of merchant adventurers

The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire

by Stephen R. Bown

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (Anchor Canada), 2021

$24.95 / 9780385694094

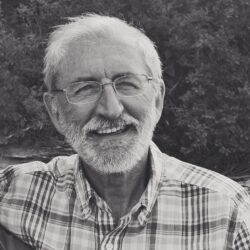

Reviewed by Daniel Francis

*

When I finished graduate school in the mid-1970s and rejoined the work force I got a job researching the history of the fur trade in northern Quebec. The Quebec government was preparing to flood eastern James Bay for a mammoth hydroelectric project and was providing grant money to study the area before they inundated it. Our project was to develop learning materials for Cree schools but it morphed into a more academic study of the historical relationship between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Indigenous people. I spent every day squinting at rolls of microfilm containing the company’s records all transcribed in the ornate penmanship of the eighteenth century (which, I suspect, is why I wear glasses today). At that time the HBC archives resided in London but a full set of documents was available at the National Archives in Ottawa, which is where I paid my dues as a novice historian.

When I finished graduate school in the mid-1970s and rejoined the work force I got a job researching the history of the fur trade in northern Quebec. The Quebec government was preparing to flood eastern James Bay for a mammoth hydroelectric project and was providing grant money to study the area before they inundated it. Our project was to develop learning materials for Cree schools but it morphed into a more academic study of the historical relationship between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Indigenous people. I spent every day squinting at rolls of microfilm containing the company’s records all transcribed in the ornate penmanship of the eighteenth century (which, I suspect, is why I wear glasses today). At that time the HBC archives resided in London but a full set of documents was available at the National Archives in Ottawa, which is where I paid my dues as a novice historian.

While this may sound as exciting as watching paint dry, it was actually a very interesting time to be involved in fur-trade studies. Attitudes were changing, in particular about the role played by Indigenous people. Previously a rather simplistic view had prevailed that they were passive victims of the trade, overwhelmed by a superior culture and technology. Thanks to people like Arthur Ray, Charles Bishop and others, the original inhabitants of northern Canada were being put back at the centre of the story and presented as having participated in the trade as partners with a canny sense of their own needs and objectives. Seems obvious nowadays but it wasn’t back then. All of which is to say that reading Stephen Bown’s new history of the Hudson’s Bay Company was, for me, like catching up with an old friend.

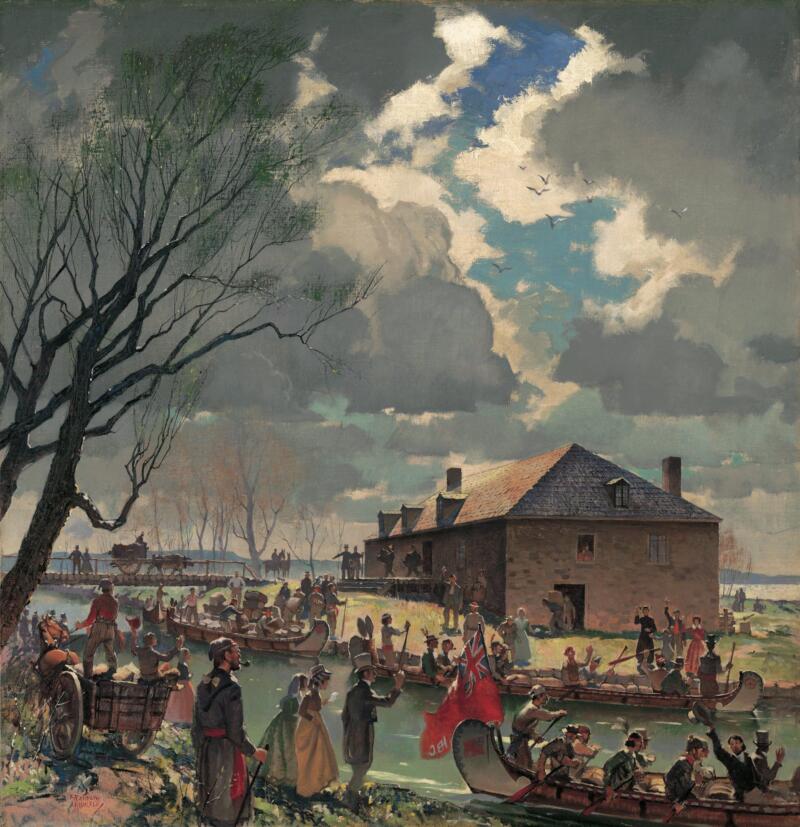

The HBC, a cabal of merchant adventurers based in London, received a royal charter in 1670 giving it the rights to conduct trade in the vast territory drained by rivers flowing into Hudson Bay; i.e. most of what is now northern and western Canada. As Bown tells us, the idea for exploiting the fur trade via the northern route belonged to two Frenchmen, Pierre Radisson and his brother-in-law Medard Chouart des Grosseilliers. (Radishes and Gooseberries to those of us who remember our grade-school history.) R and G convinced investors in England that they could out-trade their rivals in New France by sailing through the “back door” into Hudson Bay and dealing directly with the Indigenous people who lived there instead of enduring the tedious overland canoe route into the pays d’en haut.

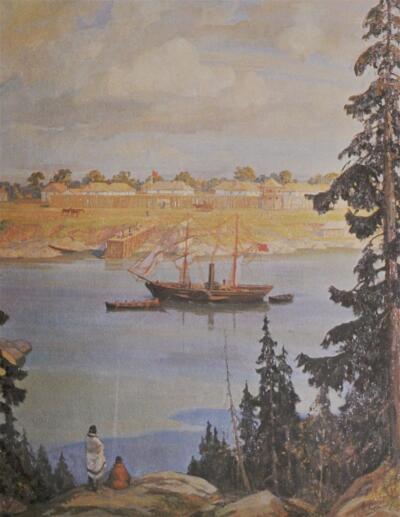

Using this geographic advantage, the company grew into a commercial behemoth, eventually. First, as Bown relates, its traders had to fight off their French rivals, learn the ways of the Indigenous people and adapt to pretty awful living conditions beside the “frozen sea”. “There were freezing winds, a lack of firewood, tedious jobs and monotonous foods,” writes Bown. Ice formed on the inside walls of the posts and even the brief summers were spoiled by hordes of biting insects. At first Company servants were remarkably incurious about their own empire and the people who occupied it. “They were perched on the edge of a foreign land for the sole purpose of doing business,” Bown explains, and that business was trading for furs delivered to them by the Indigenous trappers. In time opposition from Canadian traders forced the company’s hand and it expanded up the rivers toward the interior, establishing posts at strategic locations all across the fur country. This process involved many heroic voyages by some of the most famous names in Canadian exploration – Mackenzie, Henday, Ogden, Hearne, Thanadelthur, Matonabbee, to name just a few — and Bown relates their adventures with gusto. British Columbian readers will be especially interested in his account of how the traders pushed across the Rockies and fought for control of the trade in what was then New Caledonia.

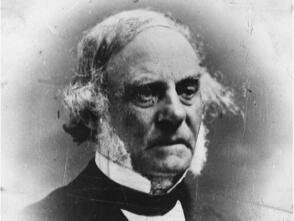

This spirited, often violent, competition came to an end in 1821 when the HBC merged with, some would say swallowed, its main rival, the Montreal-based North West Company, ushering in a period of monopoly. This is when the arch villain of Bown’s drama makes his appearance. George Simpson, a bean counter with a background in the West Indian sugar business, was the official chosen by London headquarters to get the reorganized company on the fast track to profitability. As governor, Simpson enjoyed almost unlimited power over a domain stretching from Labrador to the Pacific and he wielded it ruthlessly. He was a vainglorious martinet, indifferent to country customs, predatory when it came to local women (he had at least eight Indigenous mistresses and thirteen children, none of whom he took any responsibility for), callously indifferent to the well-being of his employees. But for his London masters, “the little emperor” was the right man in the right place at the right time, superficially charming and a talented administrator with a knack for cutting costs. In Bown’s view he was a disaster, “the greatest tragedy to befall the Company, and northern North America, since its founding in 1670.” Bown blames Simpson’s “boorish, sexist and racist attitudes” for infecting the company with a new intolerance toward Indigenous people and the easy-going relations that had been a feature of fur-trade culture.

Bown’s assessment of the impact of the fur trade on Indigenous societies is nuanced. Early on, he argues, the trade was “a form of mutual exploitation”. The First Nations used it to acquire a host of valuable trade items they did not manufacture themselves: guns, kettles, knives, pots, cloth, tobacco and so on. And if the Indigenous people became dependent on these goods, as they may have over time, so were the European traders dependent on the local people for knowledge, food and labour. The fur trade would quite simply have been impossible without the cooperation of the First Nations, which was freely given because they saw it as to their advantage to do so. This does not mean that Bown denies the changes that the trade brought to Indigenous societies. These were dramatic, and not always positive; for example the terrible epidemic diseases that periodically swept across the interior, and the heightened violence between groups made possible by the spread of guns.

Bown’s book is not a full history of the HBC. Unlike Peter C. Newman’s three-volume account that appeared to much fanfare between 1985 and 1991 and carried the story of the company beyond the fur trade into the modern period of resource development and retail trade, Bown ends his book at 1870 when the company surrendered its land rights to the British Crown in return for £300,000 and a huge chunk of some of the most valuable land in western Canada. All the remaining territory ended up in the hands of the new Dominion of Canada. This was not the end of the fur trade but it was the end of the HBC’s special privileges and seems like a suitable point to draw to a close one chapter of the company’s development.

Anyone familiar with the history of the fur trade will not find much new in Bown’s account. I felt reading it that nothing had changed in our understanding of the trade in the decades since my own immersion in the company’s records. I would have appreciated a bit more analysis of how the history of the company has been interpreted since E.E. Rich produced his classic account in the 1950s. On the other hand there is nothing wrong with a familiar story well told. Most readers will enjoy the thoughtfulness and verve of Bown’s narrative and be grateful that he has chosen to keep the story of the Hudson’s Bay Company alive for another generation to discover.

*

Daniel Francis is the author of thirty books, principally about Canadian and BC history. His latest is the bestselling Becoming Vancouver: A History (2021), was reviewed by Patricia Roy, and a previous book, Where Mountains Meet The Sea: an Illustrated History of the District of North Vancouver (2016), was reviewed by Trevor Carolan. Editor’s note: Daniel Francis has also reviewed books by Martha Black, Lorne Hammond, & Gavin Hanke, Peter Neary & Alan Collier, Ben Bradley, and Mark Leiren-Young. He lives in North Vancouver. Visit his website here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1361 A cabal of merchant adventurers”

I certainly liked “Madness, Betrayal, and the Lash”, Bown’s book on Geroge Vancouver he did a few years back. I’ll seek this one out too I think.