1340 Canada and Vietnam revisited

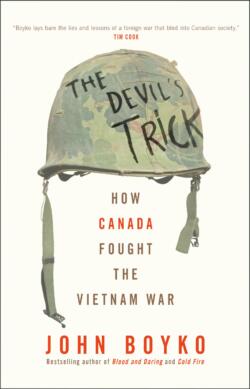

The Devil’s Trick: How Canada Fought the Vietnam War

by John Boyko

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (Knopf Canada), 2021

$32.00 / 9780735278004

Reviewed by Howard Macdonald Stewart

*

Six Easy Pieces. John Boyko has written a compelling, largely anecdotal history of Canada’s involvement in the Americans’ long years of war in Indochina. It consists of six chapters, each built around the personal experiences of Canadians involved in that war, from its beginning in the 1950s to its aftermath in the 1980s. Those half dozen stories are outlined below, but there is a great deal more rich detail in each chapter, derived from extensive interviews and a wide range of archival and secondary material.

Six Easy Pieces. John Boyko has written a compelling, largely anecdotal history of Canada’s involvement in the Americans’ long years of war in Indochina. It consists of six chapters, each built around the personal experiences of Canadians involved in that war, from its beginning in the 1950s to its aftermath in the 1980s. Those half dozen stories are outlined below, but there is a great deal more rich detail in each chapter, derived from extensive interviews and a wide range of archival and secondary material.

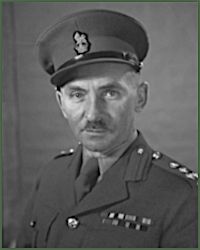

First, we follow Sherwood Lett into the early days of the morass. A distinguished hero of the Second World War who rubbed shoulders with prime ministers, Lett left a stellar career in law and diplomacy to lead Canada’s team on the International Control Commission (ICC). Together with partners from India and Poland, Canada’s ICC staff were expected to oversee Vietnam’s transition from battered, divided, post-colonial survivor to peaceful, united, independent country. It was supposed to happen very quickly, to reduce the risk of another world war. Ho Chi Minh’s communist forces had defeated their French colonial masters at Dien Bien Phu in the spring of 1954 and now a national election would be held in mid-1956 to determine who would govern the liberated country.

In the meantime, the ICC would oversee humanitarian efforts to ensure the safety of hundreds of thousands of refugees. Some were fleeing south, away from what Lett described as Ho Chi Minh’s “dictatorial, totalitarian, ruthlessly efficient regime” (p. 28) in the newly minted Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Others poured north to escape the “mass arrests, savage beatings, torture, and… extrajudicial murder” (p. 26) of anyone suspected of leftist sympathies in South Vietnam. These waves of refugees suggested that many ordinary Vietnamese had less faith than the international community in the efficacy of the proposed election.

The ICC meanwhile was becoming “increasingly impotent… [in a country] teetering on the edge of chaos” (p. 28). Canada’s ICC staff were “hard working and courageous” (p. 29), albeit uniquely unprepared for this impossible mission. Unaccustomed to a place like Saigon, they had to learn to boil their drinking water, take malaria medicine, and sleep under mosquito nets. In the meantime, with much help from the dubious and corrupt democrats of the south and their CIA supporters, and the more popular but no less ruthless regime of Ho Chi Minh in the north, the country was hurtling towards another brutal conflict. North Americans would call it the Vietnam War; for the long-suffering people of Indochina, it was the American War.

The election never happened, yet the ICC continued to function in the years that followed, its mandate ever fuzzier and its capacity to influence events ever smaller as the governments in Hanoi and Saigon did their best to neutralize it. Other players continued to find the ICC useful, however. The US, for example, had come to rely upon information from Canada’s ICC staff. And, as the American military presence in the south began its exponential growth, Canadians would be called upon to run interference in other ways too. As Hugh Campbell, Canada’s ICC commissioner from 1961-63, later revealed, “I was bloody ashamed of the things I was required to do [to cover for the Americans] … [yet] if you did not, you would be in a very difficult position” (p. 40).

This was the context for the assignment of Blair Seaborn, the next Canadian actor introduced by Boyko. Seaborn’s job as secret negotiator between Washington and Hanoi would turn out to be even more futile than that of the ICC. It reflected Canada’s genuine desire to help avert a looming bloodbath, but was confounded by the Canadians’ need to stay on the right side of the Americans. Like the ICC, Seaborn was used by American players who wanted not peace, but victory over the communists.

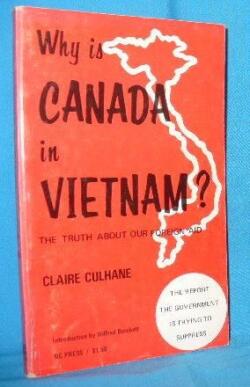

The scene is set, then, for the appearance of another sort of Canadian actor: an activist named Claire Culhane. A young communist in the 1930s, Culhane was accustomed to speaking truth to power in North America. So, as Boyko points out, it’s surprising that she was allowed to go to South Vietnam at all. The RCMP had apparently closed their file on her by 1963 when Culhane was sent to help manage a TB hospital outside Saigon. Canadian support for the hospital was a response to American pressure to “do more to help out in Vietnam.” It did help patients, for a while, with much help from Culhane’s organisational skills. But she would eventually discover that a new Canadian boss at the hospital was sharing their patients’ files with the CIA, and these were being used to support a murderous counterterrorism campaign. Plus ça change.

When Culhane could no longer stomach this backing of the US war effort, she left. Before leaving, she trained a young woman named Nga to work as a secretary in the hospital; days after a tearful farewell with Culhane, Nga went home to visit family in a nearby town called My Lai where she and five hundred others were massacred by the American military. Culhane went home to become one of the most outspoken critics of Canada’s support for the Vietnam War. By then, a growing chorus of voices had begun to decry Canada’s complicity and the extent to which our prosperity was being fuelled by the bloodbath in Southeast Asia. Culhane herself eventually published a book entitled Why is Canada in Vietnam? The Truth About Our Foreign Aid (1972).

When Culhane could no longer stomach this backing of the US war effort, she left. Before leaving, she trained a young woman named Nga to work as a secretary in the hospital; days after a tearful farewell with Culhane, Nga went home to visit family in a nearby town called My Lai where she and five hundred others were massacred by the American military. Culhane went home to become one of the most outspoken critics of Canada’s support for the Vietnam War. By then, a growing chorus of voices had begun to decry Canada’s complicity and the extent to which our prosperity was being fuelled by the bloodbath in Southeast Asia. Culhane herself eventually published a book entitled Why is Canada in Vietnam? The Truth About Our Foreign Aid (1972).

It was their war, not ours, but we sometimes helped mitigate the pain and suffering it caused. For one thing, we accepted many Americans who wanted no part in it. Boyko points out that Canada has long been a sanctuary for Americans fleeing their country’s wars, starting with the 46,000 British colonists who fled north from the new republic in the 1780s. Many young men from both sides in the American Civil War also found refuge north of the border. So Joe Erickson from Minnesota, and the 50,000-100,000 others who fled to Canada to avoid fighting in Vietnam, were hardly the first.

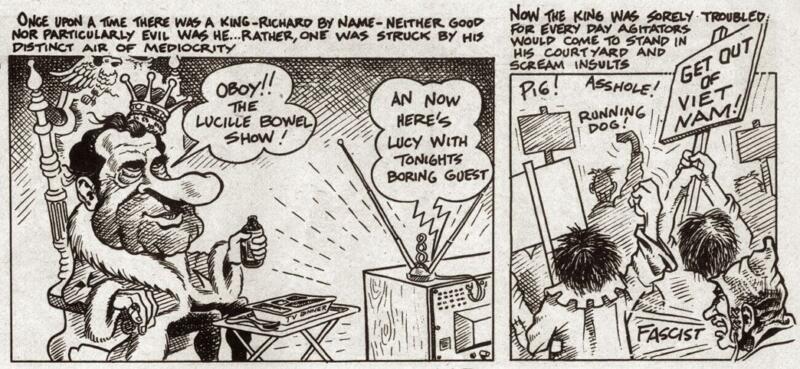

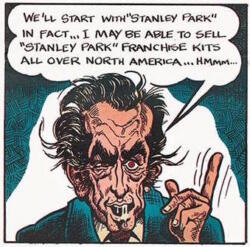

Boyko does a good job of showing that, while Canada accepted and eventually benefited greatly from the contributions of thousands of Americans like Erickson, these young men were not always greeted with open arms in the 1960s and 70s. Deserters in particular met hostility from many quarters. The office of the American Deserters’ Committee in Vancouver was raided by the RCMP ten times in 1969 alone. Vancouver’s outspoken mayor at the time, Tom Campbell — a quintessential Campbell with Highland feuds in his DNA perhaps — made it clear that “…the law should be used against any revolutionary whether he’s a US draft dodger or a hippie… I don’t like draft dodgers and I’ll do anything within the law that allows me to get rid of them” (p. 120).

Boyko’s next profile, of Doug Carey from southern Ontario, confirms that many Canadians sided with Tom Campbell more than with the draft resisters. Carey was one of thousands of young Canadians who volunteered to fight on the American side in Vietnam. Their number is harder to estimate than the number of young Americans who came the other way, but Boyko’s research suggests it was between twelve and forty thousand. Many, like Doug Carey, have borne a legacy of post traumatic stress ever since. As time went on, he and others would slowly gain insights into PTSD, a condition that would finally gain formal recognition among psychiatrists treating damaged men returned from Vietnam. A study of PTSD among Canadian Vietnam vets found that fully two thirds of them suffered from it at some point.

Most other Canadians, though, have found it easier to banish the worst of those nightmares from our consciousness. After all, we were only accessories to those crimes committed from the highlands of Laos to the Mekong Delta, not their perpetrators. Our conscience was further salved by our vigorous response to the plight of refugees like Rebecca and Sam Trinh, who fled the region in the wake of the final communist takeover in 1975. By 1990, 60,000 refugees from southeast Asia would find new homes in Canada. Like the war resisters, they were not universally welcomed. The debate over their immigration followed a familiar pattern of disagreement between nativists and others worried about the impacts of this wave of non-white “others,” and those Canadians — initially the minority — who were prepared to welcome them. As we did from the American war resisters, Canada would eventually benefit greatly from this new blood. As with the war resisters, it was one of those infrequent occasions when our political leaders demonstrated more courage than fear.

John Boyko has done a good job of showing us how we made our mark on that American war, and it on us. But what was the “devil’s trick” of his title? “Convincing our leaders that war is desirable, the rest of us that it’s acceptable, and combatants that everything they are doing and seeing is normal or, at least, necessary” (p. 1). The Indochina experience was so horrifying that more people than usual spotted this trick. Yet recent misadventures elsewhere in Asia demonstrate how soon we forget. One of the most disconcerting things about Boyko’s account of our role in Vietnam is how much of the story was repeated in Iraq and Afghanistan.

*

Howard Macdonald Stewart is an historical geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s. His memoir of a youthful bicycle trip down the Danube with war hero and debonair cyclist Cornelius Burke, Bumbling down the Danube, was published in The Ormsby Review in 2016, and his memoir, The Year of the Bicycle: 1973, followed in 2020. He is also the author of the award-winning Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour, 2017), as well as a popular Remembrance Day reflection, Why the red poppies matter. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years. He is now writing an insider’s view of his four decades on the road that followed his perambulations of 1973, notionally titled Around the World on Someone Else’s Dime: Confessions of an International Worker. Editor’s note: Howard Stewart has recently reviewed books by Andrew Scott, Catherine Nolin & Grahame Russell, Howard White, Wade Davis, Bill Arnott, Seth Klein, and Liliane Leila Juma.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1340 Canada and Vietnam revisited”