1280 To end all wars … again

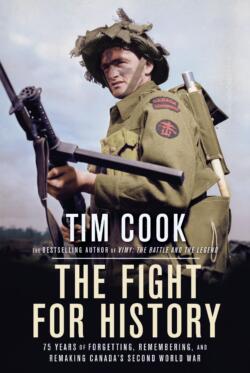

The Fight for History: 75 Years of Forgetting, Remembering, and Remaking Canada’s Second World War

by Tim Cook

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Allen Lane), 2020

$25.00 / 9780735238374

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Editor’s note: On previous Remembrance Days at The Ormsby Review we’ve published moving and personal essays and reflections by Michael Sasges, Howard Stewart, and Jo-Anne Fiske. This year, Ron Verzuh’s review of Tim Cook’s The Fight for History: 75 Years of Forgetting, Remembering, and Remaking Canada’s Second World War arrived at an ideal time, so here it is — a few hours early to mark Remembrance Day, 2021. — Richard Mackie

*

To End All Wars . . . Again: War Historian Calls on Canadians to Better Remember Their War Heroes

To End All Wars . . . Again: War Historian Calls on Canadians to Better Remember Their War Heroes

I’m a child of the Sixties. Had I been an American drafted to serve in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, would I have dodged it? Had I been a young man when the Second World War began, would I have enlisted? Such were my thoughts while reading military historian Tim Cook’s search for why Canadians have forgotten what he calls the “Necessary War.”

Another question arose as I read Cook’s argument for more monuments and “commemorative acts.” Would I have wanted to be remembered for participating in either war? For Vietnam, undoubtedly I would not. Oh, and make no mistake; many young Canadians fought in that war. For the Second World War, it becomes a question of how I would want to be remembered.

Cook leaves not doubt about where he stands. He wants monuments — all sorts — to help Canadians remember the courageous soldiers, sailors, fighter pilots and merchant mariners, the men and women who fought that war and often died in it. But for me, the anti-war adult, all war is unnecessary and avoidable. All war is evil. All war is wrong. All war benefits only the arms manufacturers and the sabre-rattling politicians so eager to sacrifice a nation’s youth.

Whoa! Not so quick there, anti-war activist. What to do when a Hitler comes along with the goal of world domination? Do you just hide and let others do the dirty work? So where does that leave us anti-war types?

Should we agree with the Royal Canadian Legion, which Cook lauds for its many efforts to keep the memory of the war alive in our minds, to keep the fight alive for recognition? For a time, the veterans’ organization balked at the idea of “living monuments” such as libraries or community centres. It is a good idea, in my view, but Cook explains the Legion’s position, while also outlining the objections to placing more statues.

It’s tempting to argue that this is merely a rehash of what we already know about Canada’s participation in both World Wars. We know about the slaughter of young Canadian soldiers. We know about the role of women in munitions factories. But how much do we know about the failure of successive governments to acknowledge the role of the thousands who died?

This history purports to tell us what we don’t know or at least what we should consider anew about the many aspects of the war that changed the lives of all Canadians forever. How does author Tim Cook do this? With each chapter, he uses his historian’s tools to inform readers of the “75 years of forgetting,” and he does not hide his personal view that Canada has done veterans a disservice by not remembering their sacrifice enough or consistently.

Along the way, I learned that a Canadian acted as an adviser on the film The Great Escape. Six Canadians were there, but “the Canadian contribution to the escape was erased.” It was a similar story in the many films about the war from American and British studios that glorified the role of each countries’ soldiers.

I was also made aware of the horrendous sacrifice Canadians made when sent into an unwinnable battle for Hong Kong. Japan finally made a formal apology that alleviated some of the anger the Hong Kong veterans felt, but their “fury was also stoked by the idea that the Necessary War had lost meaning for most Canadians.”

Cook also reports how veterans seethed with anger and resentment when Brian and Terrence McKenna aired The Valour and the Horror, a 1992 CBC TV series that criticized the politicians and the military leaders for their failures during the war. Cook also did some seething, saying veterans’ felt their role was “reduced to shame and scandal.”

He characterizes the three-part series as portraying Canada’s part in the war as “a sequence of defeats, disasters, and disgrace.” In the chapter “Denigration,” he explains that the McKennas were motivated by the view that propaganda about the war “had perverted the truth for decades.” He is critical of how they approached their task, arguing in part that “they were guilty of inserting fabricated language.”

The brothers and their show are repeatedly criticized in the book. Only the Canadian government takes a greater lashing from Cook. He traces Ottawa’s slowness to revive concern for how Canadians were dismissing veterans’ service to the country. When the government merged the army, navy and air force with a change to similar uniforms, this “gutted the morale.” The new Canadian War Museum gets a safer ride, but government delays also take a hit.

There is an excellent chapter on the internment of Japanese Canadians during the war, a well-known stain on Canada’s past. Another chapter portrays First Nations as worthy warriors who often do not get the same treatment as other veterans. Another tackles the diminishing image of Canada as a world peacekeeper with Cook arguing that our involvement in the U.S. wars in the Middle East brought that role to an end. And in still another Cook tells of Canada’s shameful refusal to allow German Jews to be given safe haven here.

Throughout the book, filled with many stirring photographic memories, we continually encounter Cook’s main purpose: to promote more remembrance of Canada’s fighting forces. To strengthen his argument he taps veterans’ memoirs, articles in the Legion magazine, novelists, comments from prominent journalists such as Charles Lynch and historians like Jack Granatstein, among Canada’s top war historians.

Cook and Granatstein are long-time fighters for a more prominent place for military and war history in the academic pantheon. Both argue that such history has been relegated to the bottom rung. In 1998, Granatstein suggested in Who Killed Canadian History? that social and labour history took up too much space. It was a declaration of war with Granatstein battling for more big “national” histories and fewer local accounts of what he considered insignificant events.

The Fight for History is a unique new approach to recounting Canada’s many experiences of war. Cook is a professional historian with a long list of credits. But my reading of this book poses an anti-war activist’s dilemma. What do we gain by promoting the increased remembrance of Canada’s role in the bloodiest war in history?

Cook documents the “Make Love Not War” generation, my generation, whose “anti-war beliefs … ranged from benign neglect to open hostility.” Toward the end, he suggests that those hard anti-war sentiments have been tempered by age and world events such as the war in Afghanistan. And yet, many of us aging baby boomers have not developed an appetite for remembering a horrific event that came before we were born.

Other historians have taken different, less advocacy-driven approaches to recounting the world wars. Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars, for example, explored the motivations behind conscientious objection to the First World War. Jonathan Vance’s Death So Noble did a creditable job of explaining Canada’s attempt to come to terms with the horrifying losses in that war.

Cook covers some of that territory, but in this latest book — he has written many — he paints a sympathetic picture of the fighters and the families of “the fallen.” This is not an anti-war book. Yes, war is bad, but we must never forget those who died. Of course, Canadians need to be aware of the terrible losses suffered in wartime, but how do we believe that perpetuating and ennobling the remembering is somehow helping to end all wars?

I’m not insensitive to Cook’s cause, but I think we also need many more books like those of Hochschild and Vance. Books and movies about war abound. Last year alone I could have watched at least six major productions on war, including the monumental Ken Burns work on the Vietnam War. But how many histories of peace appeared? How many movies depicted the peace movement?

Perhaps it’s wishful thinking that more works of art, music and literature will help us move from just remembering to imagining a world without necessary wars as an inevitable option for our future.

Postscript. As I completed this review, I got a small envelope in the mail. It had the image of a poppy on it with the words “Lest We Forget.” How timely that a message I grew up hearing would appear. Surely, we have not forgotten, nor ever will. For the anti-war activist the quest still is to end all wars.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker, recently moved to Victoria. His work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Editor’s note: His book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Wartime Western Canada will be published soon by University of Toronto Press. See here for Ron’s essay on Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy and here for Mike Sasges’ review of Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb. Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Greg Nesteroff & Eric Brighton, Nick Russell, Jim Christy, John Jensen, Charlie Hodge & Dan McGauley, Ravi Malhotra & Benjamin Isitt, Allan Bartley, Eric Sager, and Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner for The Ormsby Review. All his reviews may be viewed here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1280 To end all wars … again”

So many soldiers of the second world war came home with emotional scars that never healed.

I interviewed one who never talked about the war because it was to painful to relive.

I asked if I could write a book about him. He said only after he died. It would bring back to much pain he lived with all his life.

That is why those stories must be kept alive, so their sacrifice isn’t forgotten.

Currently my book is in the editing process. I hope to get it out by next remembrance day.

Maybe watch for it ‘The Boy Who Cried Soldier’