1240 Stumps, sawmills & speculation

Becoming Vancouver: A History

by Daniel Francis

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2021

$36.95 / 9781550179163

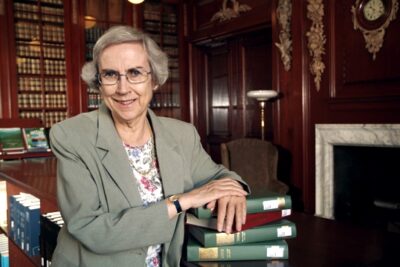

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

*

Daniel Francis, a native of Vancouver, rues Vancouver’s apparent loss of its history and hopes that knowledge of the past may avoid handing it over “to the forces of global consumerism” (p. 5). This history of his hometown provides informed, informative, and enjoyable reading.

Daniel Francis, a native of Vancouver, rues Vancouver’s apparent loss of its history and hopes that knowledge of the past may avoid handing it over “to the forces of global consumerism” (p. 5). This history of his hometown provides informed, informative, and enjoyable reading.

Francis finds three, often overlapping, main themes in Vancouver’s history. Conflict between those who wanted to attract capital for economic development and those who preferred to maintain the environment emerged early, as shown by one of the many anecdotes that effectively support his arguments. It is the case of Deadman’s Island (a former Indigenous burial ground) adjacent to Stanley Park. In 1899, Francis Ludgate secured a federal lease on it for a sawmill. Workingmen saw an opportunity for jobs; the mayor and residents of the fashionable West End wanted a park. Despite years of litigation, neither side won. It reverted to the federal government which, during the Second World War, established HMCS Discovery, a naval training station there. In another case many decades later, public protests led Marathon Realty, the Canadian Pacific Railway’s (CPR) real estate arm, to abandon Project 200 which would have had high rise residential and office towers replace Gastown and much of the Strathcona residential area. Strathcona faced other challenges and, despite some early losses, largely survived because its residents and their allies fought to protect their homes and Chinatown from urban renewal and a freeway.

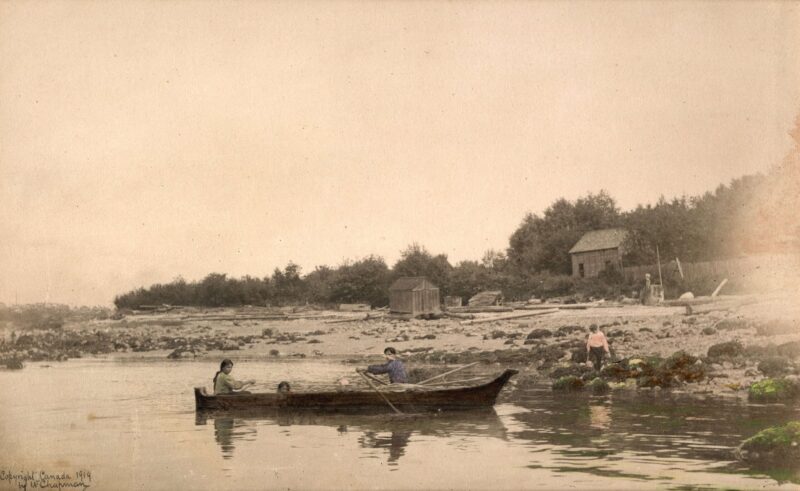

A related theme is that “Vancouver has always been about real estate” (p. 3). It began in the 1860s when three English immigrants pre-empted what became most of the West End where they expected to find commercial quantities of coal. Hitherto, it had been the domain of the Musqueam people who shared the region with the Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. The pre-emptors never mined coal but profited from a rise in land values.

Much of the real estate theme concerns the CPR. One of Francis’s nominees for the title of “founder of Vancouver” is William Van Horne, its general manager. He chose the site, acquired over 6,000 acres of land from the government and private owners in return for extending the railway westward from Port Moody, gave the city its name, and oversaw the survey of its streets and the location of major buildings. The CPR remained a major player in Vancouver real estate. It developed subdivisions such as Shaughnessy Heights, influenced the location of the City Hall by donating land, and eventually contributed to the city’s evolution to post-industrial status by selling its False Creek lands to the provincial government. The province in turn used them for the BC Place stadium and the site of Expo 86 which drew the attention of foreign capitalists to Vancouver. Subsequently, the province sold the Expo lands to a Hong Kong tycoon who built, in Francis’s words, “a small village of high-rise condo towers and townhouses that more or less established Vancouver as the opulent ‘city of glass’ it has become” (p. 214).

“Race” is a third theme. Not only does Francis describe how land was alienated from the Indigenous residents, but he examines the anti-Chinese riot of 1887, the anti-Asian riot of 1907, the Janet Smith murder of 1924, and the uprooting of the Japanese in 1942. Following the post-war enfranchisement of Asians and the relaxation of immigration laws, the city’s Asian population has so increased that today on a per capita basis, Vancouver has the highest proportion of residents of Asian origin of any city outside of Asia. Racism has reappeared with the high cost of housing being partly attributed to Asian investors.

In addition to Van Horne, Francis nominates two others with a claim to be the “founder” of Vancouver. Chronologically, the first is Capt. Edward Stamp who established a logging camp and sawmill in 1865. The second was John Deighton (“Gassy Jack”) who opened a saloon in 1867. Francis, however, wisely proposes that the title could go to the Indigenous residents who were well established along the shores of Burrard Inlet and the Fraser River when the first European, José Maria Narváez, a Spanish explorer, visited in 1791.

Using representative figures to illustrate incidents brings Vancouver’s history to life. Chief August Jack Khahtsahlano, who represents the Indigenous people, gave Major J.S. Matthews, the founder of the City Archives, much information about the region before white settlers arrived. The story of Frank Rogers, a socialist and labour activist who was murdered in 1903 during a strike against the CPR introduces conflicts between capital and labour while Helena Gutteridge and Rev. Andrew Roddan respectively show concern for women’s suffrage and the unemployed. The seamier side of Vancouver is represented by Joe Celona, a bootlegger and brothel keeper, and by several police chiefs who tolerated such activities. Paul Spong, a founder of Greenpeace, introduces the environmental movement. And, of course, such colourful mayors as L.D. Taylor, G.G. (Gerry) McGeer, and Tom “Terrific” Campbell appear as Francis outlines civic politics.

While accounts of individuals add to the liveliness of the book, Francis does not ignore the city’s economy as it evolved from a sawmilling and railway town into an industrial one whose growth was stimulated by shipbuilding and other heavy industries during two world wars, and post-war transitioned to a post-industrial city. No study of Vancouver could omit the port and so Francis mentions trans-Pacific shipping, the grain exports that followed the opening of the Panama Canal, and the coastal trade.

Nor does Francis neglect daily life. Perhaps his grandmother’s taking him by streetcar from his Point Grey home to downtown movie theatres explains his fascination with streetcars and his appreciation of different neighbourhoods and their particular characteristics. In addition, he notes the emergence of various architectural styles such as the Beaux Art Dominion Trust Building (1910), through the Art Deco Marine Building (1929) and the modernism of the B.C. Electric Building (1957) as well as the city’s contribution to residential architecture, the “Vancouver Special.”

In 250 or so pages, Francis could not possibly cover every aspect of the city’s history so listing omissions may be quibbling, but there are some imbalances. He looks at the beginning of professional theatre in Vancouver with the creation of the Everyman Theatre Company in 1946 and its collapse after a long legal dispute following its production of Tobacco Road, a play deemed obscene by the authorities. Yet, he does not mention the Theatre Under the Stars which every summer for over two decades beginning in 1940 performed operettas every summer in Stanley Park. Education too gets short shrift. Apart from some private schools, schools are ignored. Granted that the University of BC and Simon Fraser University are technically outside the city limits, but UBC deserves more than a walk-on role and SFU is important for more than radicalism in the late 1960s.

The fine arts appear with such events as the opening of commercial art galleries beginning in the 1920s and the founding of the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (1925) and the Vancouver Art Gallery (1931). Occasional quotations from semi-autobiographical fiction by Ethel Wilson, Wayson Choy and Peter Trower give evidence of a literary tradition, but apart from Red Robinson, the DJ who emceed the Vancouver performances of Elvis Presley and the Beatles, the only other reference to music seems to be a reference to the Cellar Jazz Club and that is because it hosted poetry readings. Where is the Queen Elizabeth Theatre and the decade-long summertime Vancouver International Festival? The Symphony which has performed for over a century? The Opera which has operated for more than half a century?

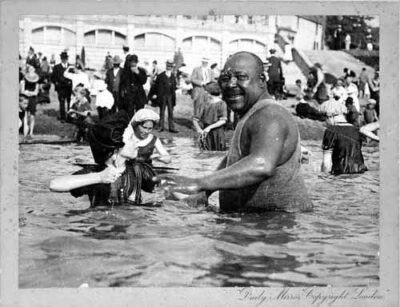

Similarly, there’s an imbalance with sports. Francis, who remembers childhood visits to see baseball games at Capilano Stadium presents a short history of a succession of professional baseball teams and the notable amateurs, the Asahi, a pre-war Japanese team. Yet, apart from a photograph of the Vancouver Millionaires who won the Stanley Cup in 1915, ice hockey is ignored despite the Vancouver Canucks three times coming close to winning the Cup and whose last minute failures twice generated riots. Similarly absent are the BC Lions who didn’t roar in ’54 but have since won several Grey Cups. As examples of Vancouver’s “world class” aspirations, the British Empire and Commonwealth Games of 1954 and the Winter Olympics of 2010 do receive their deserved place in the story.

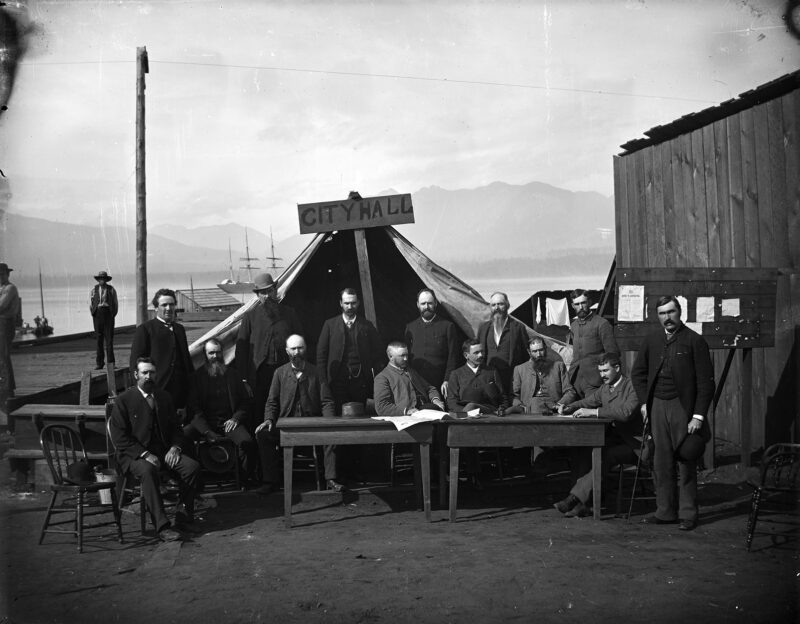

The end notes and a long list of suggested readings, essentially a bibliography, attest to the extent of research. Francis has delved into books, journal articles, newspapers, theses and the collections of Major J.S. Matthews. Some well-chosen and captioned illustrations complement the text although a few images, notably an informative map of Indigenous place names, are not well reproduced.

By the end of the 1980s, thanks to “Vancouverism,” the city was proud of having become a global metropolis. “Vancouverism,” the creation of several city planners, emphasized “a balance of heritage conservation and urban renewal; and a sustainable environmental footprint” (p. 217). It eschewed freeways and encouraged consultation with citizens. At the same time, Francis regrets that the city has failed to solve the persistent problems of the Downtown East Side, especially homelessness and the drug and sex trades. He notes how the COVID pandemic has increased the inequalities between rich and poor. Yet, he sees brighter pictures such as the formation of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Partnership to construct housing on two parcels of land that the federal government no longer required and transferred to them.

Not surprisingly, given Francis’s desire that knowledge of the past may avoid handing the city over “to the forces of global consumerism” (p. 5), the preservation of heritage buildings in Gastown pleased him but he regrets the demolition of single family homes and their replacement by apartment blocks or “monster” houses.” Let us hope that this excellent book — likely to be the “standard” history of Vancouver for some years — will inspire more Vancouver residents, both new arrivals and old timers, to have greater respect for the city’s natural beauty and its historic built environment.

*

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. She is the author of Vancouver: An Illustrated History (Lorimer, 1980) and The Illustrated History of Canada: British Columbia. Land of Promises (Oxford University Press, 2005), with John Herd Thompson, and is known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989), The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007), all published by UBC Press. Her most recent books are Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012) and The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Royal BC Museum, 2018). Editor’s note: Patricia Roy has recently reviewed books by Grace Eiko Thomson, George M. Abbott, Jesse Donaldson, Linda Kawamoto Reid, John Endo Greenaway, & Fumiko Greenaway, Kotaro Hayashi, Fumio Kanno, Henry Tanaka, & Jim Tanaka, and Ian Ferguson.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1240 Stumps, sawmills & speculation”