1215 Couplets of inspired brushstrokes

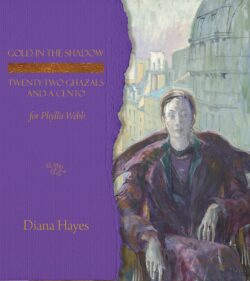

Gold in the Shadow: Twenty-Two Ghazals and a Cento for Phyllis Webb

by Diana Hayes

Salt Spring Island: Rainbow Publishers, 2021

$24.95 / 9780973440874

Gold in the Shadow is available here and here

Reviewed by Isabella Wang

*

The poetry community flourishes on a synergism of influence, friendships, and what poet Stephen Collis calls “the poetics of response.”[1] These resonances collect throughout Diana Hayes’s Gold in the Shadow — a long, serial poem virtuoso responding to the lilting lines and ‘golden shadows’ of Phyllis Webb’s painterly and poetic repertoire. Structured as “twenty-two ghazals and a cento” — one for each consecutive night working on this project — Hayes’s couplets impart a synchronous spirit to Webb’s “anti ghazals” in Water and Light (1984). Together, they celebrate and continue Webb’s innovative explorations into “the local, dialectical and private”[2] possibilities of the free-verse ghazal.

The poetry community flourishes on a synergism of influence, friendships, and what poet Stephen Collis calls “the poetics of response.”[1] These resonances collect throughout Diana Hayes’s Gold in the Shadow — a long, serial poem virtuoso responding to the lilting lines and ‘golden shadows’ of Phyllis Webb’s painterly and poetic repertoire. Structured as “twenty-two ghazals and a cento” — one for each consecutive night working on this project — Hayes’s couplets impart a synchronous spirit to Webb’s “anti ghazals” in Water and Light (1984). Together, they celebrate and continue Webb’s innovative explorations into “the local, dialectical and private”[2] possibilities of the free-verse ghazal.

In the ghazal, there are no enjambments or evident thematic correlations bridging its couplets; however, each verse subsists on its musicality and spiritual, emotional depth. In the case of Gold in the Shadow, Hayes’s couplets dance like inspired brushstrokes — au courant, enthralling, and profoundly moving. As a friend who visits Webb regularly and a fellow cohabitator of Salt Spring Island, her lines capture the solace of Webb’s “opal moons” and local weather in the ghazal’s transformed canvases of a conversation:

How is it I drift in and out inconspicuously?

SYOWT’s stone bowl floods, the opal moon’s salinity.

Elsewhere, the musical registers of Webb’s own poetry are directly heard:

I recite your lines past the broken shell of my ear.

Here and then gone, the tumbled bay receding.

Like the “tumbling bay,” Webb’s words evince a permeating presence that comes and goes in Gold in the Shadow. Engrafted, they appear perfectly at home in the ars poetica of Hayes’s attentive readership and response.

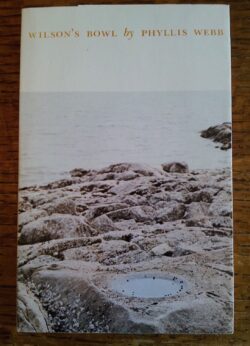

More conversations unfold in Ghazal V, one of Hayes’s most unique and interactive segments. Each couplet engenders a reverberation of Webb’s work in “postcards,” “painted premonitions: beaks, […] Scented brush strokes, rising,” and through the remobilization of the poet’s own questions. Whereas Webb, in Naked Poems (1965), introduced a minimalist form of poetic questions and responses, these inquiries now structure the hybrid expanse of Hayes’s ghazals in concert with lines from Wilson’s Bowl (1980):

What are you sad about? Doting, unfaithful, true?

The nuthatch with burnished breast and kohl eyes cries but does not sing.

In “Twenty-Two Lines: A Cento for Phyllis,” the memorable chords of Webb’s ghazals are arranged into a found segment of two interconnected ghazals. Repositioned to form new and meaningful relationships, Webb’s “pretty pebble, divine bird, honourable tree” greets “the secret heart of a poem” for the first time, and her voice is what ultimately lingers in the final pages of Gold in the Shadow.

Writing, for Webb, is at once a private and political activity. In observing the small joys and occurrences of the everyday, her lines in Water and Light attest to a labour that goes into writing and producing bodies of work for women across the passing of ordinary hours:

The women writers, their heads bent under the light,

Work late at their kitchen tables.[3]

Hayes’s ghazals, composed entirely at night, align with similar sentiments. At times when poetic composition meets challenges, the couplets themselves are transformed by a process wherein “the hours become years. Silences erase stanzas.” Understandably, the ghazals in Gold in the Shadow are deeply embodied. From a visual translation of Webb’s painting, Spirit Mountain, into “manganese blue and rain on a cumulus day,” to the olfactive of “inhaling slivers of rain,” Hayes’s singular couplets are complete poetic experiences in themselves that entice the imagination of the body’s collective senses. Choreographed in the couplet,

The heart riding in its hooded calash follows the Seine.

Like love and death, I am counting, counting.

Her end repetition of “counting, counting” aurally intuits a subtle homage to the distinctive rhythmic pulses first adopted by John Thompson and his ghazals in Stilt Jack (1978)[4]. Where she writes of “Thompson’s ghazals. He sits between couplets, listening,” he is indeed hearing the words and between.

Although the ghazal has traditionally been compared to the qualities of a gazelle — light and fleeting, while “galloping” from couplet to couplet with utmost intensity — Hayes employs a creative technique that pairs each ghazal with an inventory of poetic footnotes on the accompanying page. The carefully curated content of these footnotes varies from a title of Webb’s book or painting that Hayes is referencing, to the “song repertoire” of the Bewick’s Wren that “forsakes the songs of the father” in a couplet.

Other times, where Salt Spring Island’s site-specific imagery appears as transient flickers in the “galloping” transitions of Hayes’s ghazals, her footnotes offer an extended account of the histories and stories of these places, acknowledging a personal responsibility of use. In writing that “the ghazal was the official language of my nights,” Hayes has made a language out of the relationships and compassionate influences garnered within form. In “shadowing” Webb, her ghazals are concomitantly the plum light [that] falls more golden / golden down.[5]

*

Endnotes:

[1] See Stephen Collis, Phyllis Webb and the Common Good: Poetry / Anarchy / Abstraction (Talonbooks, 2007), chapter 2.

[2] See Webb’s preface in Water and Light, where she expresses her vision for a use of the ghazal that strayed from the traditional thematic of universal love.

[3] Ghazal 3 in Webb’s Sunday Water.

[4] For more of this beautiful, consoling, rhythmic beat, see John Thompson’s Stilt Jack, ghazals XVII, XVIII, XXII, XXIII, XXVII, XXIX.

[5] A line grafted from Webb’s Naked Poems, “Suite II.”

*

Isabella Wang is the author of the chapbook, On Forgetting a Language (Baseline Press 2019, reviewed here by Michael Turner), and her full-length debut, Pebble Swing (Nightwood Editions, forthcoming October 2021). Among other recognitions, she has been shortlisted for Arc’s Poem of the Year award, The Malahat Review’s Far Horizons Poetry Contest and Long Poem Contest, and was the youngest writer to be shortlisted twice for The New Quarterly’s Edna Staebler Essay Contest. Her poetry and prose have appeared in over thirty literary journals and three anthologies. She is pursuing a double major in English and World Literature at Simon Fraser University, and is an editor at Room magazine. Editor’s note: Isabella Wang has previously reviewed a book by Danny Peart for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1215 Couplets of inspired brushstrokes”