1210 The ghosts of Blaylock’s mansion

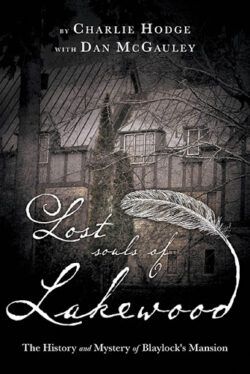

Lost Souls of Lakewood: The History and Mystery of Blaylock’s Mansion

by Charlie Hodge with Dan McGauley

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2021

$18.99 / 9781039100428

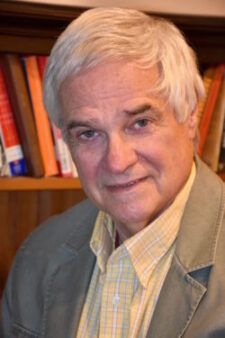

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

The Ghosts of Blaylock’s Mansion: A Romp Through the History of a BC architectural marvel is fun but lacks historical verification

The Ghosts of Blaylock’s Mansion: A Romp Through the History of a BC architectural marvel is fun but lacks historical verification

Mom used to drive us out to Blaylock’s Mansion on Kootenay Lake near Nelson to glimpse how the other half lived, I suppose, but also to share the storybook kingdom created by Selwyn G. Blaylock, the boss of thousands of Trail smelter workers, including Dad. Now, with the help of the late Dan McGauley and author and journalist Charlie Hodge, the awesome structure and lavish botanical gardens come back to life.

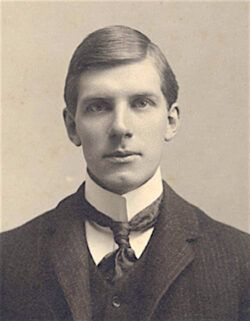

The mansion was a magical place for us, but the magic was untouchable. We could look from the curving road along the lake, of course, but this was the private property of the president of the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (Cominco), one of the largest lead and zinc producers in the world.

I knew a book was in the works. In fact, I had discussed it with co-author Dan McGauley a few years before his recent death. Dan told me he was at a loss; his laptop computer had been stolen while he was visiting Panama and it contained 100 pages of writing on the mansion. He wondered if I would be interested in co-authorship.

As it turned out, Hodge had a similar discussion and took on the task of telling the story of the mansion where Dan and his wife Louise had been caretakers for many years on behalf of the McGauley family. They had bought the place sometime after Blaylock died in 1945.

Hodge had a major sorting job on his hands. First, he had to rely on Dan’s memory for whatever was in that lost laptop. Second, Blaylock did not leave a memoir or biography. Third, rumours abound about the history of the magisterial edifice.

The result is a romp through West Kootenay history that takes readers back to the days when First Nations lived on the land. To Hodge’s credit, he does not scrimp on this unwritten Indigenous past. Also to his credit, he embraced some of Dan’s eccentricities to give the book some eccentricity of its own.

One of the things that shied me away from collaborating with Dan was his insistence that there were ghosts floating about in the rafters of the old house. I met Dan several times and each time he came back to how people staying at the mansion had seen them. He even showed me pictures of what he described as orbs.

I remained unconvinced, but Hodge embraced the idea of crafting a story that would be told from the point of view of the ghosts of Blaylock Mansion. It was a tough decision. Many of us might have opted for a straight history, and Hodge does do his work in revealing it through portraits of several previous residents, including an American Civil War veteran he calls Johnnie Reb.

As a historian, I might have dismissed the ghosts in favour of facts but, as Hodge found out, the facts are not readily available. Yes, he taps the various newspaper clippings, especially the Nelson Daily News. Yes, he quotes locals willing to share memories of the mansion. And he makes use of a few local historians, Elsie Turnbull and Ron Welwood in particular. But here the book leaves us dangling as to its accuracy.

Without sources, it could not be a history. Without living relatives – few Blaylocks are left from that time – it could not be a family saga. Without the original builders, some of them immigrants seconded from the smelter during the Depression, it could not be a complete architectural study. Here is where the ghosts came in handy.

I give credit to Hodge for adopting this literary invention to recount the story. With those voices and massive amounts of speculative imagination, he has given readers something special: a ghost story laced with historical information and a flare for storytelling.

There are problems with this invention. It requires readers to suspend belief. Those of us who know some parts of the Blaylock story are likely to question the book’s accuracy. Take two examples.

Hodge devotes several chapters to the life and killing of labour leader Albert “Ginger” Goodwin. He even has Goodwin return as a ghost to haunt Blaylock, possibly contributing to his death. He speculates that Blaylock ordered Goodwin killed after he led the 1917 smelter strike. “Sure, he never fired the bullet,” writes Hodge, “but he certainly loaded the gun.” No historian has ever proven that Blaylock was involved in the radical socialist’s death.

The second example further exposes the difficulty of using ghosts to tell the tale. Blaylock’s first wife Ruperta died quite early in their marriage, leaving him with three young children. He needed a governess so he called Ruperta’s younger sister Kathleen and asked her to leave her home in Quebec and move to the mansion.

Blaylock eventually married her and Hodge has taken immense liberties with their courtship to the point of describing intimacies in the bedroom. “Kathleen was certainly skilled in the art of love-making,” he speculates. “For Blay, the experience left him dizzy with physical pleasure and mental pain.” Having Ruperta return as a ghost to shake the marital bed added to the guilt, says Hodge.

No one can know what people “feel” in historical accounts. Hodge guesses at feelings throughout the book, but none of it can be verified. Ghost story, yes, but factual history, not so much.

Who cares? you might ask. Hodge was inventive. He found a way to unravel the contents of a stolen laptop, did his own research, and delivered a rousing good account of one of British Columbia’s unique historic landmarks.

I agree. Why let the facts get in the way? After all, there aren’t enough of them to do justice to the story. So, Charlie Hodge did the only thing left to him. He told his story about Blaylock’s Mansion, using whatever was available, and he did a good job of it. I’d say Dan McGauley made the right choice.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer and historian who grew up in the Kootenays. His work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Selwyn Blaylock appears in two of Ron Verzuh’s Ormsby pieces: Codename Project 9: How a Small British Columbia City Helped Create the Atomic Bomb and The Reddest Rose: Trade Unionist Harvey Murphy. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Ravi Malhotra & Benjamin Isitt, Allan Bartley, Eric Sager, Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner, Elizabeth May, Rosa Jordan, Vera Maloff, Peter Nowak, and David Laurence Jones for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster ?

9 comments on “1210 The ghosts of Blaylock’s mansion”

His story of landscaping, grounds, gardens, and orchards is incorrect. My father, John E. Page, was responsible for what the grounds became. I should know: I was born there, July 4, 1934.