1195 A serious thinker of the labour left

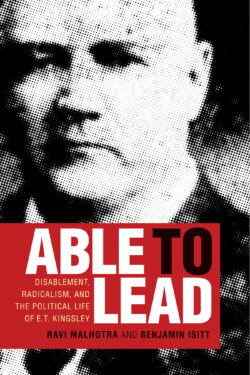

Able to Lead: Disablement, Radicalism, and the Political Life of E.T. Kingsley

by Ravi Malhotra and Benjamin Isitt

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021

$34.95 / 9780774865777

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

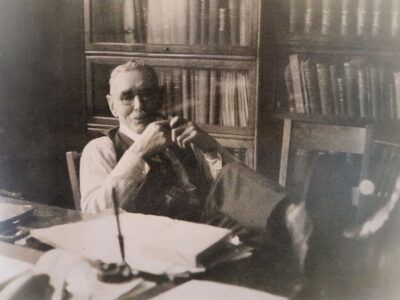

“Impossibilist” Crusader: E.T. Kingsley led the Socialist Party of Canada and edited the Western Clarion

“Impossibilist” Crusader: E.T. Kingsley led the Socialist Party of Canada and edited the Western Clarion

Eugene Thornton “E.T.” Kingsley (1856-1929) was a sharp-tongued orator in British Columbia political circles and an equally sharp-penned editor of the socialist Western Clarion in the early 20th century. Uniquely, Able to Lead probes his role in the divisive left politics of Pacific Northwest labour history through multiple historical lenses.

Kingsley, an American, became a double amputee after a rail accident in the 1890s. His marriage ended after the accident and he migrated to California and then up the coast, eventually landing on Vancouver Island. He never remarried, dedicating himself to the fight to end capitalism as leader of a strain of socialists called Impossibilists. They held that unions were irrelevant reformers when the real battle was at the ballot box. They preferred “the parliamentary road to socialism” rather than any “palliative” measures.

In Able to Lead, the authors have merged they’re respective interests and expertise, creating an amalgam of labour, legal and disability history. They devote an early chapter to tort law (civil suits for damages) specifically as it affected Kingsley’s attempts to find redress for his rail accident. They also explore the medical science related to injuries like Kingsley’s and the treatment available.

They then unfold the chronology of Kingsley’s unconventional life as an unorthodox radical. Both authors ensure that the book is laced with many significant labour history events from the Paris Commune of 1871 through the Wobbly free speech movements, Winnipeg General Strike and the advent of the One Big Union. His editorship of the Western Clarion and his own short-lived Labor Star as well as his work on the British Columbia Federationist, the new labour federation’s newspaper, put him at the centre of the action.

Coupled with his tireless speaking schedule, despite his disability, he captivated audiences, earning praise and respect from some and disdain from others. He also won enough support to rise to the leadership of the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) and before that Daniel De Leon’s Socialist Labor Party of America in San Francisco. Like De Leon, Kingsley was a hardliner who tolerated no breach with party policy.

For Ben Isitt, who has long studied the history of labour-left politics in B.C., Kingsley’s life-long stance against unions as ineffective social change agents might have been a complicating factor. “The principles of unionism and socialism are opposite therefore antagonistic,” stated Kingsley. “To support one is to deny the other. No man can serve two masters.” Note that he refers only to “man.” It was common usage, but Kingsley’s thinking on gender politics “was not advanced.” Nor was it so regarding Asian labour. “The working man must . . . shut out the Mongolians.” That view, too, was in keeping with the widespread anti-Asian views within the labour movement of the time.

As a disability historian, co-author Ravi Malhotra, himself a disabled person, faced a lack of evidence since Kingsley was unwilling to comment on his disability often failing to acknowledge even the value of union efforts to improve workplace health and safety laws. That absence forced some speculation. Malhotra suggests that Kingsley’s political position regarding unions “might have partly reflected his experiences as a disabled man in a trade union hostile or at best indifferent to workers who suffered impairments.” But the Clarion editor left little evidence to support that assumption. In fact, he displayed an “austere unwillingness to focus on personal matters.”

Following his career as printer, editor, fishmonger and political advocate for the working class, we meet several left-luminaries of the day and we see the Impossibilist position clash with the less orthodox Marxist views of other socialists. Although Kingsley ran for public office several times, twice federally, he failed to win election often losing his legal deposit. However, various friends were successful.

Socialists like Parker Williams and James Hawthornthwaite were elected to the provincial legislature. Others ran in municipal elections and were influential in post-SPC socialist circles. These included Richard Parmater “Parm” Pettipiece, a long-time associate of Kingsley’s at various publications and printing ventures, William Pritchard, Helen Gutteridge, Angus MacInnis (later a CCF MP) and other socialists who would run for office, including labour martyr Albert “Ginger” Goodwin. The authors provide glimpses of these shapers of B.C.’s left tradition, linking them to Kingsley.

The “Old Man,” as friends called him, maintained a steadfast belief that the labour movement was wasting its time and that put him at loggerheads with other socialists and labour leaders of the day. At times, ideological disagreement meant they refused to endorse his bids for public office.

As we follow Kingsley’s influential role in the development of the socialist left in B.C., we visit the many fissures and eventual splits before and after the founding of the Communist Party in 1921 and the creation of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, later NDP) in the 1930s.

Whatever the challenges to his position, he was unwavering. The working class needed to vote capitalism out of power. Strikes were useless. Collective bargaining was a reformist process that ended in compromise with the system that enslaved workers. It was all or nothing.

In a final battle between labour and capital, Kingsley predicted, “The earth will tremble from the shock as slaves and masters meet in the death grapple in that supreme hour.” In vintage Kingsley rhetorical flare, he declared “there will be a smell of blood in the air and the torch will light the heavens with the glare of destruction.” It was a decidedly different political era, one where fiery speeches and invective-laced editorials were de rigeur. Kingsley excelled at both.

Able to Lead presents the case for Kingsley as a “serious thinker,” not an “intellectual clown.” In doing so, it portrays the fractured politics of the B.C. labour left, providing an admiring account of the role of one man in that process. It is generously footnoted, includes four appendices, and should achieve its stated goal of encouraging a new perception of the capabilities of disabled people while also prompting a rethink of the early North American left.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker who focuses on social movements. Verzuh’s work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Allan Bartley, Eric Sager, Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner, Elizabeth May, Rosa Jordan, Vera Maloff, Peter Nowak, David Laurence Jones, Gary Steeves, and Ian Haysom for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1195 A serious thinker of the labour left”