1167 Hate mongering in Canada

The Ku Klux Klan in Canada

by Allan Bartley

Halifax, NS: Formac Publishing, 2020

$24.95 / 9781459506138

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

In the mid-1920s Canada was a hotbed for KKK recruiters . . . and they’re still here.

In the mid-1920s Canada was a hotbed for KKK recruiters . . . and they’re still here.

For almost a century, the racist and often violent Ku Klux Klan has found a home in most provinces of the Peaceable Kingdom. They no longer wear cartoon-like outfits, but they are out there all the same and they still burn the occasional cross, as Allan Bartley reveals in his readable study of Klan activity in Canada.

The motivational starting point was D.W. Griffiths’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation. Local theatres keenly promoted the racist depiction of robed and hooded heroes of the American Civil War. Reviewed favourably and frequently in local newspapers, Birth encouraged the founding of organizations of hate north of the border.

Although African Americans were a prime target, other favoured Klan targets included Jews, Catholics, Asians, eastern Europeans “and just about anybody who looked, sounded or seemed different from the white Protestant majority in Canada.” And the Canadian Klan often adopted violent tactics in pursuit of their white supremacist goals.

Socialists and communists widened the target base for those “predisposed to hate somebody.” Organizers, “were sworn enemies of communism and socialism,” wrote Bartley, and “friends to capitalists and supporters of the status quo.” At times, the links between the Klan and the Conservative Party seemed apparent – and mutually beneficial – but only in Saskatchewan did they effectively influence provincial politics.

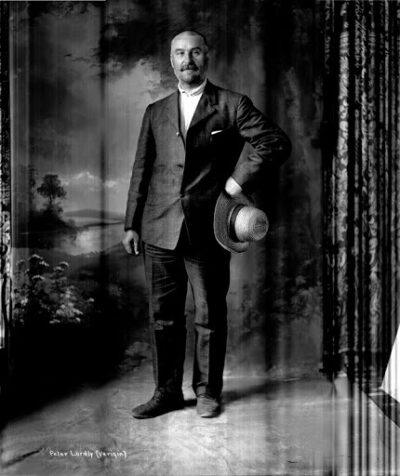

New immigrants were especially vulnerable to Klan attacks. For example, Bartley mentions the Doukhobors, a Russian immigrant sect, but only in passing. In fact, it has been suggested that Klan members may have been involved in the deadly bombing of Doukhobor leader Peter Verigin’s train in 1924 on the Kettle Valley Railway between Castlegar and Grand Forks. The bomber was never found.

Freemasons halls and Orange Order lodges in rural Ontario, with their strict loyalty to Crown and Protestantism, were perfect KKK recruiting grounds. In Barrie, the Klan was particularly popular, but local politicians soon raised concerns when a bomb was detonated near a Catholic Church.

Maritime provinces were also ripe for recruitment, especially New Brunswick where “the 1925 Conservative election victory was celebrated . . . with a cross burning on a hill overlooking the community” [Woodstock, N.B.].

Like Ontario, Alberta and Saskatchewan might have shared the Klan belief in the notion of British Israelism, a philosophy that held that “peoples of the British Isles were direct descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.” Other myths and ideologies also flourished in Klan organizing circles. Moose Jaw embraced the imperial empire, holding “the biggest Klan rally ever held in western Canada.” The rally was crowned with the burning of a large cross.

British Columbia had several klaverns (chapters), thanks to an Oregon-based kleagle (organizer) named Luther Powell. He moved to Victoria and started several klaverns, including one devoted to women, before running afoul of other Klan leaders who shunned him.

The case of Janet Smith, a Scottish nanny who worked for a wealthy Vancouver couple, primed the KKK engine. Although hatred of the Chinese and other Asian immigrants was already well established in the province, the Smith case presented a new chance for the Klan. Smith’s death was ruled a suicide, but anti-Asian Klan members believed murder was afoot (On the Janet Smith murder, see also Ginny Ratsoy’s review of The White Angel, by John MacLachlan Gray — Ed.).

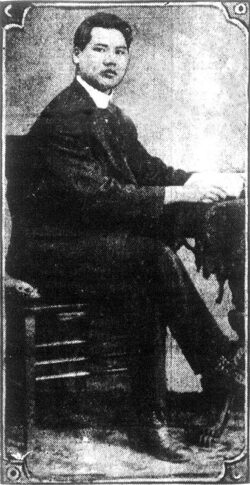

Smith had had a close relationship with Wong Foon Sing, a houseboy working for the same couple, and the Klan fingered him as the culprit. Led by a local police commissioner, Klansmen kidnapped Sing, hid him for six weeks, beat him and turned him into police who charged him with murder. The courts disagreed and released him.

The case highlighted the sort of social disruption the Klan could orchestrate, but it also signalled police willingness to aid and abet racist activity. In many communities, Bradley notes, people suspected that some police officers had Klan robes hidden in their car trunks.

Recruiters may have believed in the Klan’s racist motives, but more importantly they promoted memberships to make money for themselves. “As always and as everywhere in the Klan world,” Bartley notes, “the leadership’s main goal was making money by marketing hatred and racial violence.”

In Quebec, the rise of Adolf Hitler presented new opportunities for the Klan to trade on intimidation, coercion and threats. But it faced competition from Adrien Arcand’s National Social Christian Party, a clone of the German Nazis and Italian fascists.

When the Mohawk Nation and Quebec police made national headlines at Oka in 1990, “the Klansmen began distributing anti-Mohawk pamphlets to the predominantly white onlookers, highlighting their presence with placards urging the Quebec government to take a hard line.”

The Klan’s high point of influence may have been in the 1920s when they won public office in municipal government, school boards, Legions and social service clubs. But it did not stop there. As Bartley reports, it kept popping up through the 1970s led by the handsome and well-dressed David Duke who took credit for reviving the Klan in Canada.

In the 1980s and into the Internet era, the Klan adapted its hate mongering to the high-tech era. Now it discarded the old symbols and developed broadcasting channels and online outlets to foment hate. New names, like Heritage Front, disguised the true intent of the organization. KKK grand wizard Don Black replaced David Duke and took internet technology to a new level with his stormfront.org web site, a cyber hate machine that gained momentum after Trump’s 2016 election.

In Canada, we take pride in our role as a liberal democracy, but our own history of discrimination and our willingness to be persuaded by the newest conspiracy theory to hate others is always close to the surface. Bartley helps us remember it.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker who focuses on social movements. Verzuh’s work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Eric Sager, Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner, Elizabeth May, Rosa Jordan, Vera Maloff, Peter Nowak, David Laurence Jones, Gary Steeves, Ian Haysom, and John O’Brian for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1167 Hate mongering in Canada”

The white supremacist has been the devil for our whole planet. Thanks for writing this.