1159 Fighting Canadian inequality

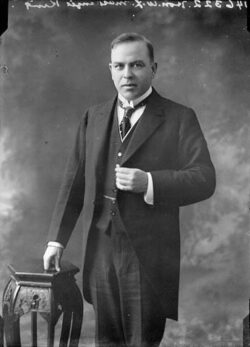

Inequality in Canada: The History and Politics of an Idea

by Eric W. Sager

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021

$37.95 / 9780228005803

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Political economists from the 1770s to the 21st century analyze Canadian inequality and ponder how to address it.

Political economists from the 1770s to the 21st century analyze Canadian inequality and ponder how to address it.

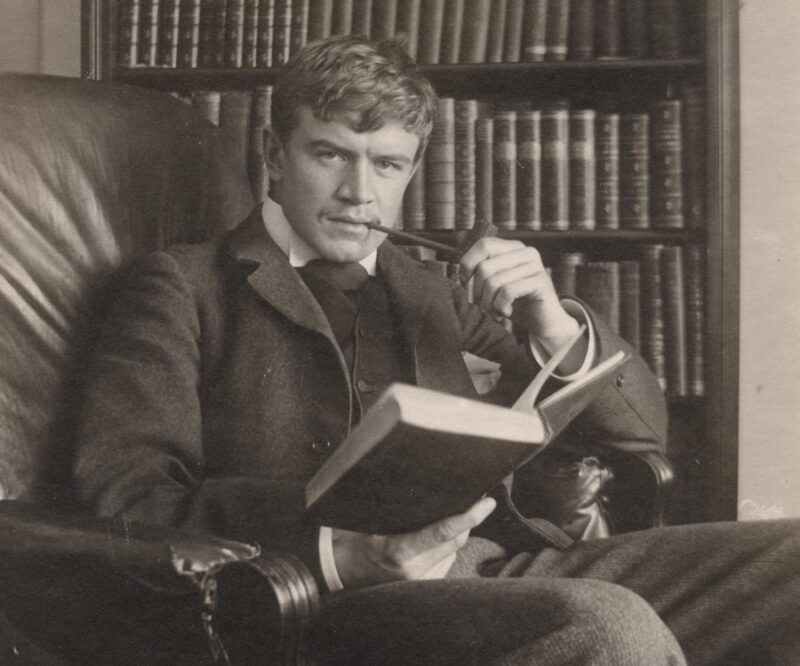

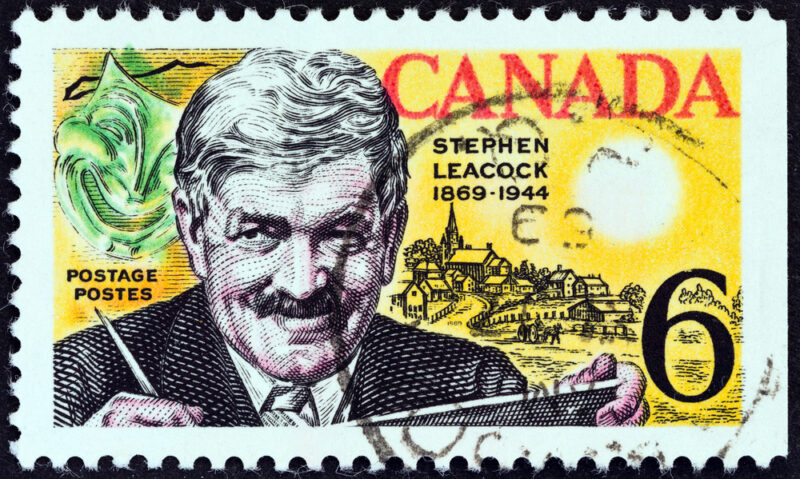

Most of us know Stephen Leacock as Canada’s foremost humorist and author of Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912), but there is another Stephen Leacock. This one figures in historian Eric Sager’s expansive study of inequality along with dozens of other erudite political economists that populate this sweeping canvas of theories about inequality’s sources and the distributive justice required to resolve it.

Leacock as a theorist falls into Sager’s category of Tory idealist. The satirist and McGill University economics professor comes late in the story of unequal treatment going back to Upper and Lower Canada. But he offers strong solutions in The Unsolved Riddle of Social Justice published in 1920.

“Few persons can attain to adult life without being profoundly impressed by the appalling inequalities of our human lot,” he wrote. Noting that Leacock saw the root of the problem in the “excessive individualism that accompanied industrialization,” Sager describes Leacock’s proposals for full employment, pensions and social insurance as “Tory idealism.”

To better understand the broader challenge of this intellectual history, we must return to the “prominent ethical-political stances relevant to inequality in our time.” Sager, a University of Victoria historian, begins in the North American colonies of the 1770s and works his through to the welfare era (1940s-1960s).

This is a study of theoretical thinking with the theorist hoping to influence public policy as the nation grew and inequality continued to prosper. Much of the action, then, takes place in the minds of the great scholars of the period. On occasion, radical reformers such as William Lyon Mackenzie, the leader of the rebellions of 1837 in Upper Canada, are examined in that context. The rebellions in Lower Canada were similarly about seeking equal treatment for its citizens in an environment of aristocratic governance.

In both cases, says Sager, “we must read the meaning of equality and inequality in the setting of its time. Inequality, in the 1830s, meant privilege and monopoly; equality meant the wider distribution of specific rights, which would enable any redistribution of existing accumulations of wealth.”

The threat of socialism inspired much thinking about inequality. It was, after all, a theoretical framework for taking action. But the churches had other ideas. “A common Protestant refrain was that socialism universalized selfishness and materialism,” argues Sager. But thinkers like Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, John Stuart Mill, and the American Henry George, with his single tax theory, all sought answers to the inequality that industrialization brought to the working masses.

In the late 19th century, the Protestant critique of wealth as a generator of inequality was embroiled in the relations of labour and capital. Labour in the form of the Knights of Labour wanted workers to get their share of the wealth and were willing to fight for it. Protestants were stymied by the new class conflict that was emerging.

The labour movement had its own theories about the problem. One popular solution was co-operation in the battle to quell inequality. Phillips Thompson was the movement’s champion for a time and his The Politics of Labour (1887) became a textbook for what Sager called “redistributive justice.”

Moving into the 20th century, Sager examines the theoretical thinking of future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, grandson of the radical, whose Industry and Humanity (1918) would help shape the notion of co-operative labour-management relations. Unfortunately, it resulted in stronger capital control of workers with employers often using company unions to stymie union organizing.

We are informed of agrarian perspectives and attempted solutions on inequality and Sager provides a critical assessment of social gospellers, men like Salem Brand and J.S. Woodsworth, and the leaders of the League for Social Reconstruction. The LSR was the theoretical grounding for Woodsworth’s Co-operative Commonwealth Federation.

In assessing labour’s attempts to address inequality, Sager leaves us with this thought: “Despite all their limits and inconsistencies, working-class engagements with inequality offered hope and inspiration.” He argues that “Labour’s reform politics was a politics of immanence” A new world was possible, indeed, immanent. In that vein, Sager suggests that such optimism tells us “our working-class ancestors have much to teach us.”

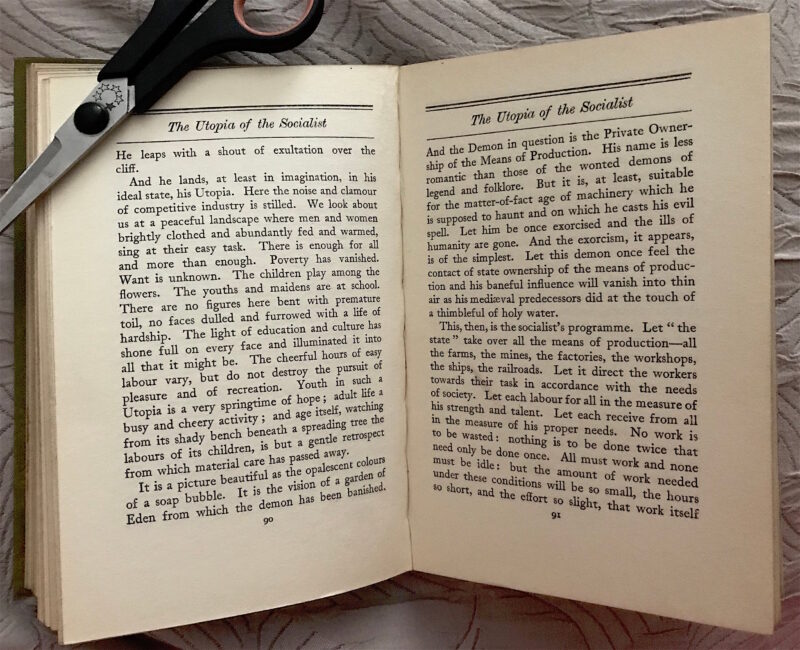

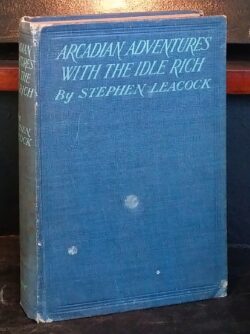

Interestingly, amidst the heady works of so many noted thinkers that have shaped the country’s social policy landscape, Sager says Leacock’s satirical work Arcadian Adventures With the Idle Rich (1914) is “Canada’s most original, enduring, and distinctively Canadian contribution to the problem of inequality.”

Sager continues his review into the 20th century, critically citing thoughts and theories on inequality from John Kenneth Galbraith, Eugene Forsey, Harold Innis, John Maynard Keynes, Frank Underhill, John Porter and many others. He concludes with the hope that his “historical reconnaissance” of Canadian social theorists and political economists “may help inspire a renewed moral vision without which there is no path into the future.”

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker who focuses on social movements. Verzuh’s work has appeared in The Ormsby Review since it was founded in 2016. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Michael Dupuis & Michael Kluckner, Elizabeth May, Rosa Jordan, Vera Maloff, Peter Nowak, David Laurence Jones, Gary Steeves, Ian Haysom, John O’Brian, and Scott Stephen for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

10 comments on “1159 Fighting Canadian inequality”

This was a lovely review of both the book and Leacock’s “Tory Idealism”. I might note that one of Leacock’s final economic manifestos, published after his death, was While There is Time: The Case Against Social Catastrophe (1945). This is a more mature Leacock than even his earlier books on political economy mentioned in the review.

Ron Dart