1138 Cariboo counterculture

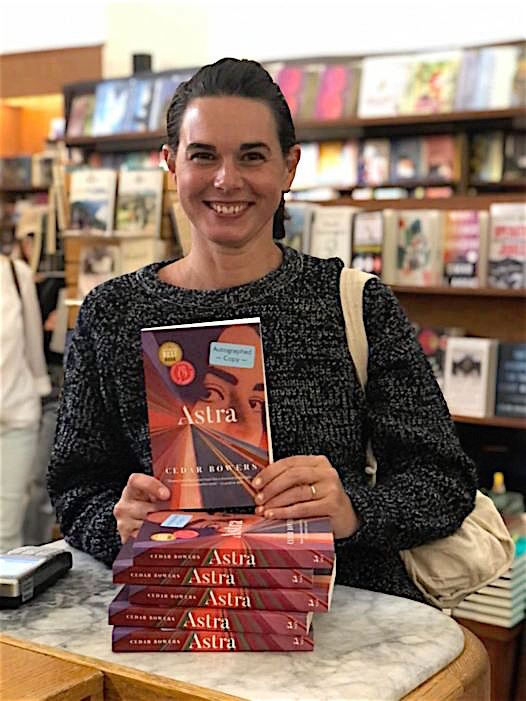

Astra

by Cedar Bowers

Toronto: Penguin Random House (McClelland & Stewart), 2021

$24.95 / 9780771012891

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

As a spectral visitor to western Canada in the 1970s, Karl Marx would have rolled his eyes at Celestial Farm. Or, more likely, he would have written an article denouncing it — barely a season old and already in free fall — as “doomed to failure.” The guy had no time for utopian socialism, which (in The Communist Manifesto) he envisioned as paltry — naively idealistic “small experiments” aiming “to pave the way for the new social Gospel.”

As a spectral visitor to western Canada in the 1970s, Karl Marx would have rolled his eyes at Celestial Farm. Or, more likely, he would have written an article denouncing it — barely a season old and already in free fall — as “doomed to failure.” The guy had no time for utopian socialism, which (in The Communist Manifesto) he envisioned as paltry — naively idealistic “small experiments” aiming “to pave the way for the new social Gospel.”

A promising swath of land (“two low plateaus of rock divided by [a] hundred acres of fertile valley”) in the Cariboo region of British Columbia, Celestial Farm is ground zero of Cedar Bowers’ engrossing, clever, and unexpectedly riveting debut novel.

Co-founded by childhood friends Doris and Raymond, the farm-habitat-community begins as an easygoing vision of communalism where principles replace rules and open-mindedness supplants stodgy convention. There, individual freedom and nonconformity would be primary commandments.

The planned “oasis” is a ruin in no time, of course.

Gloria envisions using an inheritance from her affluent family in Vancouver to begin anew. But she soon realizes that womenfolk are cleaning up much more than menfolk.

Further, Raymond, a monomaniacal jerk of a character, treasures his independence; and, certainly, he doesn’t believe in monogamous relationships. His calling, as he sees it, is to carve a utopia from a wilderness. (“[P]eople are going to write books about this place, I swear it,” he predicts). He wants to stay true to his path, so when one of his sexual partners, Gloria, announces her pregnancy, Raymond touts his honesty about his categorical unwillingness to parent and his utter lack of suitability: “He’d been called to Celestial for a reason, and nothing was going to distract him or slow him down.” (Blunt Doris, less tolerant of men after a summer of cobbling together a paradise with them, is uninterested in Raymond’s truth: “You’re not some guru, free to do whatever you want. This is your fucking problem, Raymond.”)

Gloria dies after giving birth, and Astra Winters Sorrow Brine appears in the world fully burdened by history and a father confident in his assertion that he’s not built for fatherhood.

Celestial, an Eden overrun with serpents, is Astra’s birthplace, but soon enough she’s living in Calgary and Vancouver. Although homeschooled (to be generous) she learns early to read people and create situations to serve her needs. For better or worse, she’s a survivor. As captured by Bowers, Astra’s gruelling quest is to forge the best version of herself. The odds don’t often appear to favour success.

Bowers traces Astra’s erratic development across ten chapters (titled “Lauren,” “Brendon,” “Doris,” “Sativa,” and so on); these chronological episodes portray stages or moments in Astra’s evolution where a social contact plays a significant role.

In “Kimmy,” for example, Astra is a feral child and spying on a close by house. She eventually befriends the girl, Kimmy, who resides there with comforts Astra has never experienced — a flushing toilet, a shower with hot water. The girl displays intoxicating luxuries. In turn, Astra reveals outlooks deeply informed by her father: “Oh, I don’t go to school. Raymond doesn’t believe in it. He thinks kids should learn real skills. He says school only teaches you to be a sheep”; “Raymond says sugar is poison.” Astra also introduces Kimmy to a “magic talisman,” a decahedron that her father uses to make decisions apparently guided by the cosmos.

Bowers’ early chapters focus on Astra’s adolescence, but by “Brendon,” the fourth, Astra has moved to Calgary and grown adept at the art of persona — depending on the situation she’s manipulative, self-serving, purposefully masked, or emotionally closed-off. Her facial scars (resulting from an attack at Celestial) are expertly smoothed by heavy use of cosmetics. Her transformations, are unnerving, as revealed by Bowers: the novice novelist manages who Astra is and what she’ll become in taut horror movie pacing.

Aside from immersive unfolding plot, Astra is a novel offering many pleasures. Its episodes are enchanting; all the characters — from Clodagh, who’s lived hand-to-mouth for all of her adulthood and for whom every new romance is just long wait for erupting violence, to Nick, a self-satisfied “good, moral person” in Vancouver who attends humiliating couple’s counselling with Astra. (It’s in “Nick” that we learn Celestial still exists and that it “never made money, not once in forty years.”)

Despite the distance, Celestial, along with Clodagh and Doris and assorted children, remain constant for Astra. She relies on former or fleeting Celestial residents; she runs into them, argues with them, accepts money and accommodation from them, and eventually has a child with one of them. They’re all part of her emotional DNA.

The epilogue, set in Celestial when Raymond is nearly 90 and suffering from dementia, reveals the ongoing weight of history. Written from Astra’s point of view, it’s an affecting portrait of a hard-won and wavering maturity — even though Bowers’ wanderer is still entangled with her father and his vexing ways (“He’s never had a single worry or responsibility on his whole life, so he gets to be charming,” she complains). A reluctant homecoming (Astra has avoided returning for three decades), the return makes poetic sense.

Compared to the angry Astra, the impulsive, erratic, and hot-tempered iterations of her, and the willful and irresponsible incarnation of Raymond’s daughter that people have witness or perceived, the aged Astra of the final pages is testament to the long haul that coming-of-age can be.

Fully oneself at 18, 19, or 20? No way and no how, the novel suggests. Reaching the plateau where your consciousness is as raised as it will ever be and you’re at (relative) peace with who you are, well, that may take a lifetime.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, will be out in mid-October with Now or Never Publishing. Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has also reviewed books by Glen Huser, Dustin Cole, and George Ilsley for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1138 Cariboo counterculture”