1137 Resurrecting Indigenous voices

Resilience Through Writing: A Bibliographic Guide to Indigenous-Authored Publications in the Pacific Northwest before 1960

by Robert E. Walls, edited by Darby C. Stapp

Richland, WA: Journal of Northwestern Anthropology, Memoir 20, January 2021

$34.95 (U.S.) / 9798566579900

Reviewed by John Lutz

*

The very quotable English essayist Charles Lamb wrote that bibliographies are “books which are no books,” and pretenders “in books’ clothing perched upon the shelves like false saints,”[1] presumably because they have no plot and do not entertain. Robert Walls’ Resilience Through Writing is an example of one of these “biblia a-biblia,” but contra Lamb, it does indeed entertain and between the lines it also has an important plot. Walls has compiled the published voices of Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest from the earliest arrival of scribes in the 1840s to 1960 in a successful attempt to return voice to thoughts which have been long lost in the winds of time.

The very quotable English essayist Charles Lamb wrote that bibliographies are “books which are no books,” and pretenders “in books’ clothing perched upon the shelves like false saints,”[1] presumably because they have no plot and do not entertain. Robert Walls’ Resilience Through Writing is an example of one of these “biblia a-biblia,” but contra Lamb, it does indeed entertain and between the lines it also has an important plot. Walls has compiled the published voices of Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest from the earliest arrival of scribes in the 1840s to 1960 in a successful attempt to return voice to thoughts which have been long lost in the winds of time.

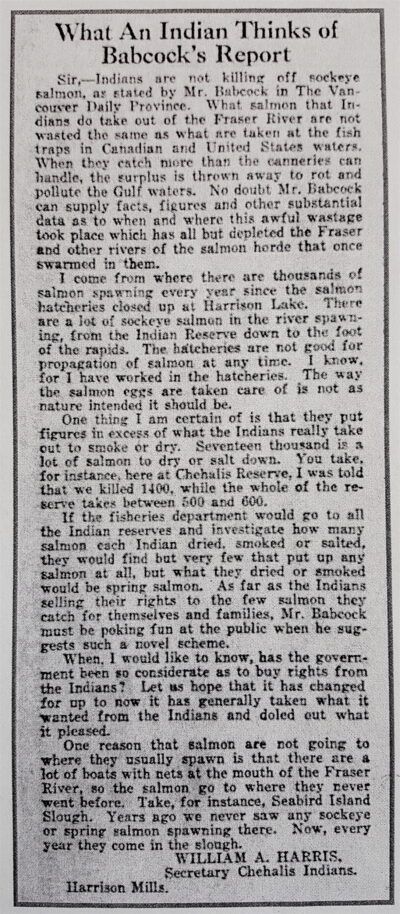

Historians struggle to find Indigenous writings and thoughts through this period as English language education was only fully in place in the latter part of the period, education was rudimentary, and there were few outlets even for the most articulate Indigenous writers. Walls has invested countless hours in a labour of love to find and bring to our attention lost writings from both well-known writers, like Chief Seattle, and the obscure, from full-on novelists to the once-in-a-lifetime letter to the editor writers.

What we discover from Resilience Through Writing, to our surprise, is that in spite of obstacles, Indigenous people were using the popular press and missionary publications from the start of settlement to convey their concerns, ideas, and creativity to a wide audience and in an abundance we could not have appreciated until the publication of this book. First with the help of missionaries and later on their own, they created publications to share their thoughts with other Indigenous people. As Walls writes, uncovering these texts “is discovering critical fragments of historical knowledge, fascinating examples of creativity and adaptation to the demands of the settler-colonial landscape” (p. 5). While recognizing the acculturative pressures of literacy, Walls also observes that, “In so many respects, writing did not erase Indigeneity; it enhanced resilience” (p. 5).

Editorial works such as this bibliographical guide — and I can think of other outstanding examples including Robert Galois’ Kwakwaka’wakw Settlements, 1775-1920: A Geographical Analysis and Gazetteer, James Hendrickson’s Journals of the Colonial Legislatures of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, and W.K Lamb’s The Voyage of George Vancouver 1791-1795 — are the Rodney Dangerfields of the book world: they “get no respect.” And yet, it is to these “not books” that researchers rely on to write their Canada, Pulitzer, and Booker prize-winning books. They are to historical scholarship what pure science is to medical breakthroughs.

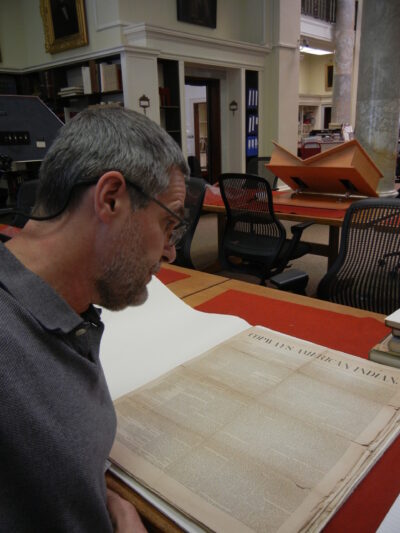

The work that Walls has invested in this compendium is awe-inspiring. He has combed regional libraries and archives, Indigenous-run and oriented publications, a wide range of digitized newspapers, and hardcopy serials in the Pacific Northwest with a concentrated focus over two years, but the book also reflects his lifetime of interest in this field. His bibliography is presented in four regional sections: 1. Coast Salish and their neighbours in western Washington, Oregon and California; 2. Coastal and plateau people of British Columbia; 3. Coastal people of southeast Alaska; 4. Plateau people of eastern Washington, Oregon, and northern Idaho.

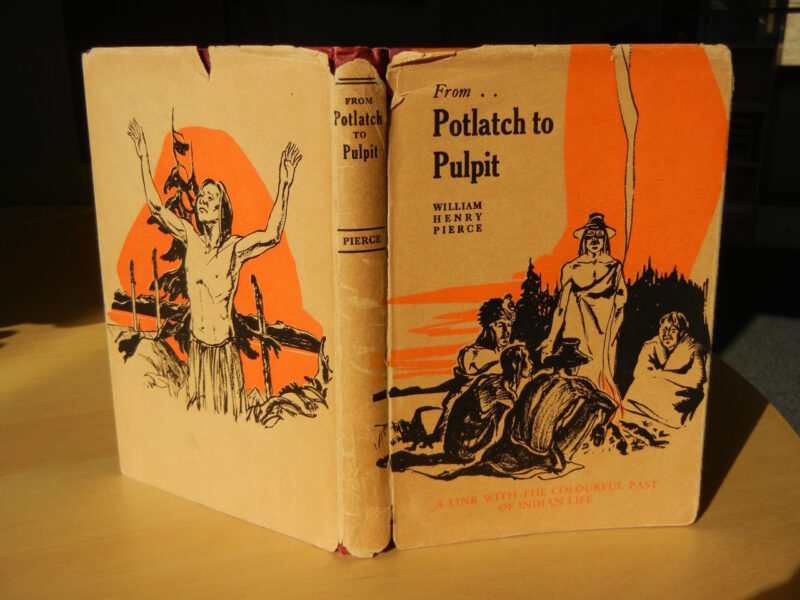

Walls’ definition of “published” is eclectic and expansive but he is emphatic that the bibliography is not exhaustive, only “the tip of an iceberg” and a reminder that much remains to be discovered. Included is any writing aimed at a wide audience and published or circulated in any form, as well as “found” writings published by someone other than the original author. Just as the scope is inclusive so is his definition of “Indigenous author,” which includes people like Constance Cox, who advertised herself as “the first white child” born in Hazelton, but who also, when strategic, identified with her Tlingit grandmother. Also included are co-authored or “as told to” narratives with non-Indigenous amanuenses.

Cracking open the spine at a random page, in this case at p. 175, you will find four entries. In one letter, published by Dan Assu in the Victoria newspaper The Daily Colonist in December 1950, we learn from the annotation that the Fisheries Department is “weeding out” Indigenous fishermen from the herring fishery. Another, by Frank Assu in the publication Native Voice, discredits Andy Paull’s claim to lead the North American Indian Brotherhood. An 1873 letter from Peter Ayessik and a dozen other Indigenous leaders in the Mainland Guardian complain of their lands being usurped with no compensation. The final entry, by “Baptiste of Sahhaltkum,” written in the Chinuk pipa alphabet of Father Le Jeune and published in the Kamloops Wawa in 1892, describes a house fire that consumed all his possessions.

In each case the culture of the writer is indicated if identifiable (here Kwakwaka’wakw, Stó:lō, and Secwepemc); a brief synopsis of the publication and description of the author (if known) is given; and sometimes more information is provided, such as additional sources. On other pages, you can find citations to poems, plays, novels, sermons, court and sport reports, legends, autobiographies, letters of condolences, and classified ads. Indexes allow the researcher to search by cultural group, author, any of the 72 Indigenous serial publications reviewed, or by broad topic. Totem poles have, for example 29 entries, disease 22.

The real strengths of Resilience Through Writing are both the one-off articles, like Makah Young Doctor’s assertion that his father did not die of natural causes but was murdered at the hop fields, which open up stories that intrigue and beg investigation, and the themes that repeat through many entries across time and space. These include demands for justice with respect to land (more than 85 entries) and racism (52 entries), and also creative outlets in the 92 entries that relate to poetry. Such are the hidden plot lines that connect the pieces and offer what almost amounts to a collective voice of issues of primary interest to Indigenous people in the late 19th to mid 20th century in the larger Pacific Northwest.

Walls admits that his coverage is strongest in the Coast Salish heartland of Washington and Oregon, and less comprehensive as the coverage spreads out from there. I noticed one anachronism, in that the Times Colonist was cited as a source in 1950 when there were two papers, the Times and the Colonist, which later combined; but having used Resilience Through Writing extensively, that is the only lapse I noticed. Finally, in terms of suggestions, the format begs for a digital database that could be augmented by readers who take up his Walls’ invitation to help fill in the gaps and increase the richness of this resource.

Why, Walls asks, “have anthropologists and historians generally ignored this legacy?” (p. 3). The answer seems obvious to me. Until now, no matter how much we wanted to hear these voices, it has been a matter of luck, not skill, to find them. We no longer have that excuse.

Charles Lamb, a prig when it came to books, also paradoxically thought “the better a book is, the less it demands from binding,” and this special memoir of the Journal of Northwest Anthropology is perfect bound (glued), in an 8.5×11” format. It is so modest in its presentation that, both by Lamb’s criteria as well as my own, it is clearly an important book. For those interested in Indigenous history in British Columbia and the larger Pacific Northwest there is much here to entertain, intrigue, and inspire research. We owe a debt to Robert Walls and the Journal of Northwest Anthropology for this generous work of scholarship.

*

John Lutz is a professor of History at the University of Victoria where his research focuses on the Pacific Northwest from the 1770s to the 1970s, particularly on the histories of race and Indigenous-settler relations. He has a keen interest in the impact of digital technologies on research, teaching and dissemination of history and is a co-director of the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History Project. He co-teaches an ethnohistory field school with the Stó:lō First Nation, was a co-founder of The History Education Network (THEN/HIER) and The Friends of the BC Archives and has served as director of the university’s Office of Community Based Research. His book, Makuk: A New History of Native-White Relations, won what is now called the Canada Prize for the best book in the Social Sciences in Canada in 2010 and his projects have won the Pierre Berton Prize from the National History Society and the Hackenberg Award from the Society for Applied Anthropology. Later this year his jointly edited book To Share Not Surrender: Indigenous and Settler Visions of Treaty Making in the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia will be published by UBC Press.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] From Charles Lamb, Detached Thoughts on Books and Reading: An Essay (1894).