1139 The late Wa’xaid: Cecil Paul

Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid

by Cecil Paul as told to Briony Penn

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2019

$30.00 / 9781771602952

*

Following the Good River: The Life and Times of Wa’xaid

by Briony Penn with Cecil Paul

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2020

$38.00 / 9781771603218

Both books reviewed by hagwil hayetsk Charles R. Menzies

*

Cecil Paul’s memoir, Stories from the Magic Canoe, and Briony Penn’s biography of Paul, Following the Good River, are best read together for full effect. Paul’s memoir is personable and intimate. We can hear him speak as he tells his histories; especially the first four chapters. The writing has the intonation of an accomplished oral story teller. Penn’s biography adds context and detail. It is part biography of Paul, part her own story of documenting Paul’s life, and part academic account of the north coast. Both books stand on their own, but they complement each other synergistically and I recommend that people read them together.

I should say that I come to this as an interested party: Paul is related to me through my own great grandfather’s second wife, Alice (see also Penn, p. 15), and Penn reached out to me to check some of the details. Like many other readers I eagerly waited for Paul’s book to come out, I read it cover to cover in one sitting, and then had to wait over a year to read Penn’s biography. It was worth the wait.

Following the Good River is like a travel guide and personal memoir in the style of Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines (but without the fiction). Penn’s account follows the narrative line of Paul’s Stories from the Magic Canoe. Penn provides the context and information that those unfamiliar with our Indigenous north coast societies and culture might need to fully grasp the nuance and depth of Paul’s own book. Penn’s structure also follows that of Paul’s Stories from the Magic Canoe. Each of her sections starts with a verbatim quote from Paul’s book, followed by explanatory mini-essays that provide the historical, ecological, and cultural details that help readers contextualize Paul’s stories. Next, we find excerpts from Penn’s own journals that document her journey of growth, and how she to connected to Paul’s life and to his work with ecologists in the Kitlope.

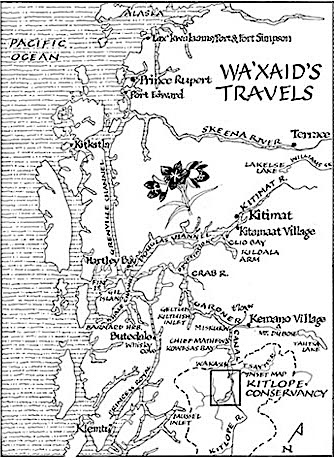

Penn’s mini-essays are replete with details about the moments, people, and events Paul talks about. For example, with reference to the return of the G’psolox Pole (Paul pp. 129-134; Penn pp. 311-314), Penn picks up the opening sequence of the NFB film on the pole and explains aspects of the pole’s cultural meaning. Penn then delves into the hard research involved in finding the pole in Sweden, how the local Indian agent in Prince Rupert bought the pole for the Swedish consul, and how in 1928 the pole was exported to Sweden. We learn later in the essay about the fifteen years of negotiations it took to convince the Swedish officials to return the pole to the Haisla. There are many more such mini-essays interspersed within Paul’s stories and the reader is left the richer for it.

For the researchers among us, we are constantly treated to details of Penn’s research process, for example: “The Bob Stewart Archives in the basement of Ryerson United Church in Vancouver is in the process of being moved … but I’m still made welcome by archivist Blair Galston. The United Church could not be more accommodating to help dig out records of Cecil at both Elizabeth Long and Alberni residential schools” (Penn p. 145). This kind of detail, borrowed from Penn’s own journals, is woven throughout the narrative. Academic texts, even the more experimental ones, typically ignore this kind of background. Indeed, important threads of Penn’s research process lend structure and fibre to the narrative throughout Following the Good River.

Penn doesn’t stop with accounts of research in the archives. She also documents her work process with Cecil Paul and the many trips she took to visit him in the act of creating his book and hers, for example:

Kitlope, May 15, 2017. We arrive at the Kitlope estuary with the migrating swallows — flashing white, iridescent green and blue-black. The chatter of excitement from them is infectious (Penn, p. 266).

Most of these journal entries date from the five or six years before publication. Another tier of entries dates from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. Two entries from the 1980s predate Penn’s first awareness of Paul. He gave a talk in Victoria that she had to leave early (Penn, p. 95). I mention these two 1980s entries as I have returned to them over and over trying to understand their placement and context in the wider story. I think they are signifiers of Penn’s longstanding interest in the issues that drew her into the Kitlope and her later work with Cecil Paul, but for me these early mentions with Paul remain ambiguous (perhaps fittingly so?).

All of these narrative snippets bring the research and writing process to life, but they do more than that: Penn brings us right into her own journey of learning. Her background as a naturalist is evident in her descriptions of landscape and the beings that animate it. Her developing empathy and connection reflects the deepening friendship she builds with Paul. Her biography of Paul is also an autobiography of sorts of Penn herself. But since she follows Paul’s narrative arc, her own storyline at first feels disrupted, disjointed. One needs to read the book differently, to mentally shift and rearrange the narrative structure to see Penn’s own story as it moves from the early 1980s to the present of the book some 40 years later. While Paul’s is a life history story, Penn’s in a certain sense is a retrospective story that begins in the present and then shifts backwards in ways that add context. Penn is an accomplished writer, and while she brings her story into play, it stays for the most part in the shadows as this is first and foremost the story of Cecil Paul.

Paul’s Stories from the Magic Canoe is a beautiful book — physically in terms of its layout and design and but more importantly in the artfulness of Cecil Paul’s life stories. The well-crafted stories in the first four chapters especially reflect the polishing and honing of repeated telling by a skilful orator. The final chapter feels incomplete, not quite polished and with many fragments and ideas competing for attention. But that makes sense to me because that final chapter of Paul’s life is waiting to be told by those who follow after him. Paul has given us the material. It now falls to those stepping in his footsteps to bring that part of his story fully to life.

These are two books I heartily recommend to fellow BC’ers. Paul’s is a straightforwardly direct, yet profound book. Penn’s adds context and texture to Paul’s stories. Taken together they will make all of us richer for having read them.

*

hagwil hayetsk Charles R. Menzies is a professor of anthropology at the University of British Columbia. His book People of the Saltwater: An Ethnography of Git lax m’oon (2016), was reviewed by Robert Muckle in The Ormsby Review. Editor’s note: hagwil hayetsk Charles Menzies has also reviewed Being Ts’elxwéyeqw: First Peoples’ Voices and History from the Chilliwack-Fraser Valley, British Columbia for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1139 The late Wa’xaid: Cecil Paul”

It is nice to see my father’s history written

I had the honour of hearing these stories

I hope people enjoy both books