1062 Pepper’s ballet and dance

Falling into Flight: A Memoir of Life and Dance

by Kaija Pepper

Winnipeg: Signature Editions, 2020

$19.95 / 9781773240831

Reviewed by Maria Tippett

*

In the early 1930s two dancers from British Columbia were invited to join the corps de ballet of Basil’s famous Ballets Russes. The offer came with one condition: Patricia Meyers from Vancouver would have to become Alexandra Denisova and Nanaimo’s fifteen-year-old Jean Hunt would also take the Russian sobriquet Kira Bounina. Times have certainly changed since the 1930s. Canadian dancers no longer have to go abroad to make their careers — in Vancouver alone there are more than five professional dance companies — and if dancers do leave the country they can perform under their own names. Nor are Canada’s dancers and choreographers dependent on appraisal from abroad because critics like Vancouver’s Kaija Pepper are fulfilling the challenge of seeing “a choreographic work as objectively as humanly possible in order to develop accurate and fair-minded description.” (p. 48). Even so, as Kaija Pepper makes clear in Falling into Flight, A Memoir of Life and Dance, this art form “It isn’t taken seriously, even by other artists” (p. 29).

In the early 1930s two dancers from British Columbia were invited to join the corps de ballet of Basil’s famous Ballets Russes. The offer came with one condition: Patricia Meyers from Vancouver would have to become Alexandra Denisova and Nanaimo’s fifteen-year-old Jean Hunt would also take the Russian sobriquet Kira Bounina. Times have certainly changed since the 1930s. Canadian dancers no longer have to go abroad to make their careers — in Vancouver alone there are more than five professional dance companies — and if dancers do leave the country they can perform under their own names. Nor are Canada’s dancers and choreographers dependent on appraisal from abroad because critics like Vancouver’s Kaija Pepper are fulfilling the challenge of seeing “a choreographic work as objectively as humanly possible in order to develop accurate and fair-minded description.” (p. 48). Even so, as Kaija Pepper makes clear in Falling into Flight, A Memoir of Life and Dance, this art form “It isn’t taken seriously, even by other artists” (p. 29).

If the reader expects this award-winning author and dance critic to tell us why this is so they will be disappointed.

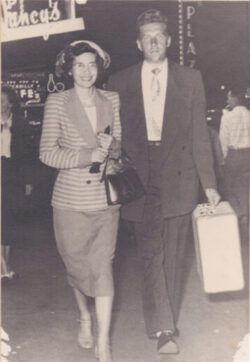

The connective thread running through Falling into Flight charts Pepper’s year-long therapy sessions with Dr. B. The therapist helps her to overcome her severe claustrophobia — elevators, public washrooms and crowded restaurants were no-go areas. He also enables Pepper come to grips with her unpredictable Russian-born mother Zina. “‘I’m at the end of my tether!!’ my pretty dark-haired mother would scream, coughing in spasms of fury as her throat seized up” (p. 35). “Your mother didn’t make room for you to be seen and heard, she didn’t know how,” was Dr. B’s observation (p. 40). Andy Kaija, Pepper’s father, was raised in the Finnish community of Thunder Bay, Ontario, before settling in Vancouver’s East Side where he drove a truck for Lafarge Cement Company. Andy was easier on his four children: he was silent and mild-mannered and had a taste for the Romantic poets.

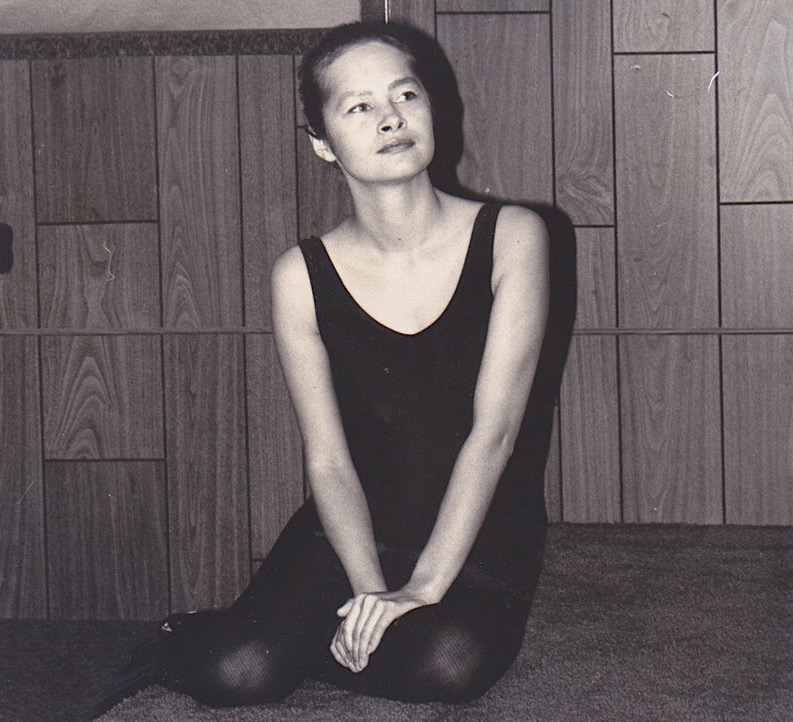

Though ballet is largely off stage in this memoir, Pepper, who began ballet lessons at the age of six, vividly recalls her first performance; pasting images of ballerinas in her Micky Mouse Club scrapbook; watching Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn perform on the Ed Sullivan show; and attending her first ballet — it was Coppélia.

And while Pepper had what can only be described as a tortured relationship with her mother, it was Zina Kaija who laboured over her Singer sewing machine to make her daughter’s ballet costumes; Zina who accompanied her daughter to her ballet lessons; and Zina who took her daughter to her first ballet, Coppélia.

Pepper stopped taking ballet lessons when she turned fifteen. Three years later she studied the dance technique of Martha Graham and a few years after that, while enrolled in communication arts at Concordia University, she turned to jazz ballet.

It was in Montreal where “Writing turned out to be a good fit.” Where, Pepper’s “relationship with the art form [of Ballet] could develop without the intense public scrutiny of performing life in front of an audience, or even in front of other dancers in a studio” (p. 115). And also where she “came to value critical writing for the way it extended the short-lived theatrical existence of most productions of putting dance onto the page, corralling the ephemeral moments of performance into words and sentences that supposedly live forever” (p. 115). When Pepper returned to Vancouver, following a stint in the U.K., she became a leading critic and the author of three books on dance.

When I finished Falling into Flight I wanted to read more about Pepper’s observations on dance, about which she writes so splendidly. I wanted more quotations from her journals, which would have enlivened her text. And I wanted more dates that would have told me when the events she discusses happened.

Even so, Kaija Pepper’s memoir brought back my own memories of attending ballet lessons, of wearing my first tutu and of negotiating my teenage years around a difficult mother who also made my ballet costumes. But it is Pepper’s passionate and knowledgeable writing on the critic’s role in relation to what she calls “the underdog in the art world” that convinced me that dance is worth taking seriously (p. 29).

*

Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Since her formal retirement in 2004, she has written four books, including Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017), reviewed here by Catherine Nutting. Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979), which also won the Governor General’s Award for non-fiction. Editor’s note: Maria Tippett has also reviewed books by Mary Fox, Ruth Abernethy, and Roger Boulet for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1062 Pepper’s ballet and dance”

I liked your review Maria but thought that a few points would be worth correcting whether they were those of the author, Pepper, or you. First of all, the young BC ballet dancers that you reference became part of the ballet de corps of OBR (Original Ballet Russe) in the late 1930s. Both were students of the amazing June Roper whose dance school acted as a hot bed for future ballet dancers. The two that you mention, Patricia Meyers and Jean Hunt, became members of Wassily de Basil’s troupe in 1938 and late 1939 respectively. In an interview with Roger Stone in 2007, Jean Hunt (later Jean Haet) relates how she had no choice for the Russification of her name, Kira Bounina, as it just appeared above her door one day. David Lichine, the choreographer, was responsible for this. On the other hand Patricia Meyers was older and given a choice, and she decided she liked her name, Alexandra Denisova. Denisova married her dancing partner Alberto Alonso not long after joining the company in May 1939 in Melbourne. She was 19 years old. They separated in 1944 while living in Havana. Alonso went on to be the co-founder of National Ballet of Cuba. Meyers/Denisova/Alonso became Galian after her marriage in 1958 to the piano stylist and arranger, Geri Galian. They worked on many TV shows together in the 1950s where dance was still a major element of entertainment. She died in 2018. Here is her obituary in the LA Times. After the war, Hunt/Haet moved to LA and also worked in several films before turning to teaching in the Bay area. I gleaned much of this interesting stuff from Leland Windreich’s 1999 book, June Roper, Ballet Star-Maker. Pictures of both Meyers/Denisova/Alonso/Galian and Hunt/Bounina/Haet can be seen her in Lichine’s original production of Graduation Ball in Melbourne in 1940.

And of course Patricia Meyers and Jean Hunt were as you hint, only two of a steady stream of young dancers that the Texas-born Vancouver teacher June Roper sent to the international companies in the 1930s and 1940s, as detailed in both Lee Windreich’s excellent book on Roper or my own book, Dance Canada: An Illustrated History. In 1938 Rosemary Deveson, 16, was chosen for the de Basil company at the same Vancouver late-night audition as Meyers/Denisova, and became Natasha Sobinova (“I was named for a Russian tenor I had never heard of,” she recalled). In 1939 Ian Gibson auditioned for the Denham Ballet Russe company and followed Leonid Massine to Ballet Theatre, where he danced several of Nijinsky’s roles. In 1940 Audree Thomas, as Anna Istomina, joined Massine. In 1941 Duncan Noble also went to Ballet Theatre and the same year Robert Lundgren was invited to join the Denham company, but was refused permission by the War Manpower Commission and had to wait until 1943 and an invitation from Massine to start his professional career at Ballet Theatre. Roper also sent Joy Darwin to the Ballet Jooss (1937), Margaret Banks to Sadler’s Wells (1939), and Peggy Middleton to Hollywood, where she became Yvonne de Carlo. Dance Magazine called Roper “North America’s greatest star-maker.” Hardly surprising.

Thanks for clueing me into your book Max. June Roper’s daughter, Elizabeth was also a teacher of some note as well. This incredible flow of artistic energy stemmed from Russia naturally.

In a November 8, 2002 review in the LRB of Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia by Orlando Figes (Allen Lane, October 2002), Joseph Frank says, “A new myth of the peasantry, however, soon found artistic expression in the Ballets Russes. The workshops of Abramtsevo had already combined Russian folk arts and crafts with Art Nouveau stylisations, and a group of young men (Sergei Diaghilev, Alexander Benois, Leon Bakst) now began to see peasant art as falling in line with the new European taste for the exotic and the primitive. The Ballets Russes, arising from an attempt to create a fictive Russian past using artistic techniques that would appeal to the most sophisticated contemporary taste, took Europe by storm.”

As I say in a 2019 essay on Leon Bakst, modern ballet is what brought all of the arts together and, not surprisingly, all the best artists including Stravinsky, Debussy, Picasso, Chagall and many others. The ballet as envisioned by Daghilev struck the big chord in everyone’s mind.

Fauvism and modernism were essentially a stripping down of all pretences and revelling in one’s nakedness and essentially primitive nature.

Of all the art forms that best realized this disposition and posture was the medium of dance as envisioned by Ballets Russe. Drawing on and buttressed by visual art, design and original music, the productions staged by Serge Daghilev, Leon Bast and choreographers, Mikhail and Vera Fokina, did more for “art” than any other cultural event in the West.

At the poetic epicentre of Ballet Russe was, initially, an erotic flowering of folk costumes and dances of Russia and eastern Europe particularly with Jewish themes. The authenticity with which these dances and costumes spoke to people was significant.

This should come as no surprise at all considering that the main artistic force of Ballet Rouse was Leon Bakst, a Belarusian Jew who had changed his name from Lev Rosenberg in order to succeed in that new Western “occupation:” artist.

Decades on, critics and historians would say that with later productions and reorganizations, ballet degenerated into melodrama and vacuous orientalism — a lot of style and not much substance.

However, there was a point when the artistry and the substance of these productions was the torch leading artists and people out of the tunnel of the 19th C and all that it included, especially sexual repression. Moreover, the waves Ballet Russe (and later iterations) made went all the way to the Pacific coast and fired the imaginations and energies of the young dancers mentioned in the review and in your detailed response of others who went through dance schools in BC, especially those of June Roper.

And to think that it had as its launching pad, a modernist art magazine that appeared in 1898 called Mir iskusstva (World of Art). The founders and writers were Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and Sergei Diaghilev.

According to Hanna Chuchvaha, “the miriskusniki promoted understanding and conservation of the art of previous epochs, particularly traditional folk art and the 18th-century rococo.” (The Art of Printing and the Culture of the Art Periodical in Late Imperial Russia (1898-1917)). 2012 PhD thesis.

All of this was, of course, a slap in the face to Vladmir Stasov the arch Russian imperialist arbiter of all things Russian. He hated them and eve called Diaghilev “a decadent cheerleader” in print and Mir iskusstva “the courtyard of the lepers” (an image borrowed from Victor Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris).

Ahhh, but what a disease to contract!

Hi, Grahame, to respond to the query at the top of your comment: I don’t cover this early history in Falling into Flight; the discussion about the fascinating story of Vancouver dancers and the Ballets Russes is entirely the reviewer’s. Falling into Flight is actually not a history book, but a memoir about family, childhood, psychotherapy and — at the centre of it all — dance. My previous books were Vancouver dance histories, though they do not focus on the Ballets Russes connection, which my good friend and colleague Lee Windreich covered so well in a couple of books. He and I shared the same publisher for our dance histories, Dance Collection Danse