#852 Plenty of dust but no pilaf

Lands of Lost Borders: Out of Bounds on the Silk Road

by Kate Harris

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Vintage Canada), 2018

$21.00 / 9780345816788

Reviewed by Howard Macdonald Stewart

*

Kate Harris’s tale of bicycling the Silk Road of Central Asia, her Land of Lost Borders, came out a couple of years ago and it describes two rides, one in 2006 and another, longer one five years later. Like the author, her story has aged well.

Kate Harris’s tale of bicycling the Silk Road of Central Asia, her Land of Lost Borders, came out a couple of years ago and it describes two rides, one in 2006 and another, longer one five years later. Like the author, her story has aged well.

I have to admit I was not positively predisposed towards this book. I worried it might be a “been there, done that” kind of read, wherein I would smugly second-guess the author. After all, I’d cycled many thousands of miles across continents when I was younger than her, and then spent time in a lot of the places she would traverse, from Turkey and Central Asia to Nepal and India. My grumpy predisposition was further stoked early in the book as the author went on about her fascination with travel to Mars and the noble history of European exploration. It felt adolescent, escapist, and elitist, oblivious to the school of hard knocks of which, I told myself, I was an alumnus, whereas Harris was forever flitting off, apparently never actually having to work for a living and oblivious to the history of colonialism so closely tied to our European explorers’ vaunted “Age of Discovery,” etc.

I’ve never been much interested in the planet Mars; I thought Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles (1950) was dumb. I don’t even like Mars bars. But I have to admit, I was fascinated by those bold European “explorers” when I was younger and I was curious about Harris’s trip. What would it be like to cycle across Central Asia or Tibet, let alone in Nepal or northern India? Despite a lifelong addiction to bicycles, I never dreamed of cycling in places like Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan when I was there. Being a pedestrian was challenging enough. And I remember thinking how hideous it would be to cycle the narrow, crowded highways of Nepal or Uttar Pradesh.

So I wanted to see what was going to happen, and by the second part of her story, about the much longer ride that started in Istanbul, I was hooked.

Then I began to worry about other things. Was this the kind of book I was supposed to have written? Might publishers and their readers be more attracted to a lively tale of adventure penned by a bright young Rhodes scholar than to my own turgid and pedantic accounts from decades spent as fly-in temporary help for international organisations? I had parental kinds of worries too, about Harris’s day-to-day concerns – for example, all those flat tires she started to have were almost certainly a sign of tires wearing thin. And I worried about dust.

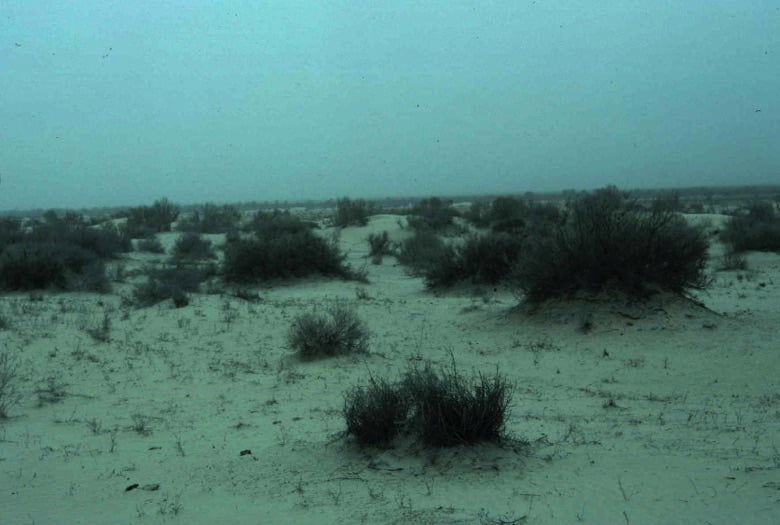

Harris said she regretted they didn’t get a closer look at the sad remains of the Aral Sea but I believe she and her partner Mel were wise to give it a wide berth. She mentions the dust they encountered on their way across Uzbekistan. Did she and Mel realise how toxic that dust can be? It blows up not just from the country’s pesticide-laden cotton fields but also from the dried bed of the Aral Sea, now mostly a desert wasteland of salt and pesticide residues.

The last time I was there, a young woman doctor shared with me her frightening reports of the mysterious new ailments they were finding in the region. She was almost certain, she said, that these were due to toxic residue blowing up from the parched sea floor. Islam Karimov, the Stalinist thug who was in charge when I was there, and still in charge when Harris rode through, didn’t want to hear about it.

Cycling is one of the hungriest modes of transport and cyclists inevitably think and talk a lot about food. This is especially true when one isn’t sure where the next meal is coming from, but you know for sure that you’ll have to expend many calories to get there. So I could relate to the author’s frequent food talk which, in turn, gave rise to one of the book’s great mysteries. I don’t remember a single reference to pilaf. Yet in my experience, this rice dish, often laced with mutton and always drenched in oil, was something one ate at least once or twice a day in Central Asia, and especially in Uzbekistan. Have Uzbeks turned their back on pilaf since I was there? It would be like Americans turning their backs on hamburgers.

It was also in Central Asia that I started to find Harris a more sympathetic character. Not because of any shared adventures — the rigours of riding across Uzbekistan or Tibet far surpassed any cycling adventures I’ve ever had, not matter how intrepid I might have felt at the time — but because Harris began to show signs of (what I consider) more humanist sensibilities. She mentions, for the first time that I noticed, her own immense advantages: “… I hail from a day and age — and a country and culture — so privileged, so assiduously comfortable, that risk and hardship hold rapturous appeal” (p. 150).

She soon concedes too, that much human exploration has been in pursuit, not of knowledge for its own sake, but of profit, of greed. Still she insists, and I agree, the real goal of exploration ought always to be to return home and share your tale.

Perhaps stirred by the Aral Sea disaster, and already chastened by her experience in airless microbiology labs back in the US, Harris also begins to shed her awe of science, or at least to recognise its limits in explaining the universe and our place in it. I still wasn’t sure if she had abandoned her plan to travel to Mars, but it was starting to feel like it. Seeing the reality of Mars-like desolation in Central Asia may have dimmed her ardour. Certainly, she was daunted by the devastation we humans have wrought in Central Asia. Could we really be responsible enough to be let loose on Mars? And wouldn’t all that Mars exploration money be better used cleaning up our fouled nest back here on Earth? It’s tempting to blame environmental disasters like the Aral Sea on the blinkers imposed by the “scientific socialism” of the defunct Soviet Union, until one takes a closer look at places like the tar sands of northern Alberta.

By the end of the book I was pretty much reconciled with the author. Her partner had headed home to southern Ontario to work for a community non-profit organisation and Harris herself didn’t crave a different world any more. I guessed this meant she’d renounced the Mars mission. Instead, she said, she wanted “this world done differently, done better for everyone,” and she hoped “the right words could launch us there, or more accurately bring us home” (p. 276).

My philosophical-cum-political queries about the author and her evolving worldview were jumbled together with a far less complicated awe at the ride she and Mel accomplished, especially the high-altitude cycling they did in Tibet and northern India, where they climbed passes 16,000, even 17,000 feet above sea level. The only times I’ve worked for a day or two at such altitudes my guts and lungs and heart and brain have been so taxed I could barely stay upright and conscious, let alone ride a bicycle.

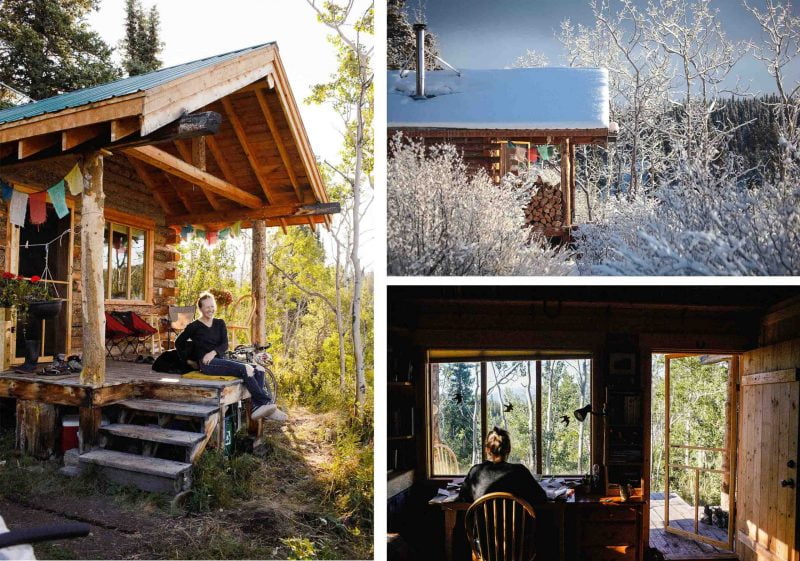

Lands of Lost Borders is a hell of a good book about an amazing couple of bike rides across some of Asia’s most challenging and fascinating terrain. It’s truly a coming of age tale and a fine piece of travel writing too. Kate Harris has earned her sojourn in Atlin, an idyllic little mining town and artist colony tucked away in the far northwest corner of British Columbia, but I don’t expect she’ll go to seed there. We’ll hear more from her in coming years.

*

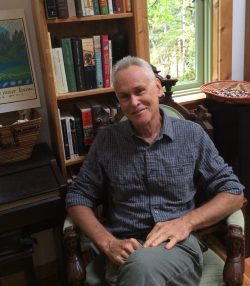

Howard Macdonald Stewart is author of Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour Publishing, 2017). An historical geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s, Howard has reviewed books for The Ormsby Review and BC Studies. His memoir of a youthful bicycle trip down the Danube with the war hero and debonair cyclist Cornelius Burke, “Bumbling down the Danube,” was published in The Ormsby Review (no. 21, Sept.-Oct. 2016), and his memoir, “The year of the bicycle: 1973,” followed in Ormsby no. 788, April 2, 2020. He has also written a popular Remembrance Day piece, “Why the Red Poppies Matter,” in The Ormsby Review no. 420, November 11, 2018, as well as many book reviews, most recently of My Favourite Crime: Essays and Journalism from Around the World, by Deni Ellis Béchard. He is now writing an insider’s view of his four decades on the road that followed his perambulations of 1973, notionally titled Around the World on Someone Else’s Dime: Confessions of an International Worker. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#852 Plenty of dust but no pilaf”