#833 A fresh water poetry anthology

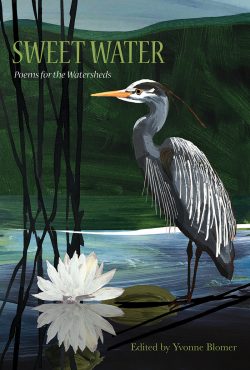

Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds

by Yvonne Blomer (editor)

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2020

$22.95 / 9781773860220

Reviewed by John Swanson

*

Sweet Water is an important and timely book, about fresh water in all its many forms — lakes, ponds, rivers, creeks and streams, wetlands, marshes, and ground water, the water under the water table. Sweet water is all this fresh water that is not brackish, not salty.

Sweet Water is an important and timely book, about fresh water in all its many forms — lakes, ponds, rivers, creeks and streams, wetlands, marshes, and ground water, the water under the water table. Sweet water is all this fresh water that is not brackish, not salty.

This book is about how we weave the wisdom of water into our stories, and about how our stories create our world.

Yvonne Blomer, the editor of the book, has collected 111 poems from 111 different poets, most from Canada and about half from British Columbia. It’s a formidable list — most of the poets have been published in multiple journals and many have won prestigious poetry prizes. Blomer, who served as Victoria’s Poet Laureate from 2015 to 2018, has written an introduction which she ends by saying: “We are reminded… of the profound grief we feel for our part in damaging the natural ecosystems of the planet. Here the poets say: Listen. And now is the time for listening, for deeply contemplating the planet, her watersheds, and the creatures who rely on them. It is a time for profound change.”

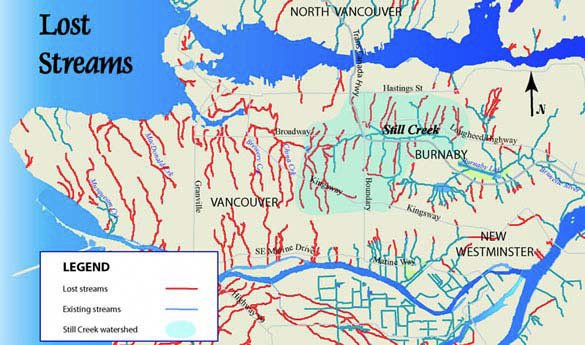

As a child I grew up in a Vancouver that still had creeks in the forest around my home – a city where there once had been 120 km of trout and salmon streams (Vancouver’s Old Streams, City of Vancouver Archives, 1978). I remember one of these creeks being filled in, covered over, to make a “safer place for children.” I spent time every summer at a lake in the Cariboo where I learned to swim, and row on the lake. And later in life we spent summers on Savary Island, “Áyhus” to the Tla’amin Nation, meaning “double-headed serpent.” For a number of years I was a trustee of a small water district that pumped and stored water from a ground water aquifer that ran the length of the island. The Savary Island Land Trust was able to save the last undivided parcel of land (350 acres) in the heart of the island, protecting a unique desert habitat and ensuring replenishment of the groundwater. All of these experiences gave me my appreciation and gratitude for “sweet water.”

And now I live in Mount Pleasant in Vancouver, two blocks from the edge of the Tea Swamp, where ancient streams, now underground, cause streets and fences to tilt and buckle, refusing to be paved and tamed. A constant reminder of what we have done, trying to bury the water.

*

Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds is in three sections: I. Sweet, II. Movement, III. Grief. The first section celebrates memories of water, of places experienced in relation to water.

From reading books of poetry I have found myself asking: “What does poetry do to work its magic?” It relates knowledge of the world as we acquire it from science and by other means, with ancient knowing of a more mysterious kind: the forces at work in the “soul” (however you understand that term), the role of intuition in our lives, the non-rational that we need in order to understand fully who we are and what our place is in the world. Sometimes prose is not up to the task of evoking a place, a feeling, and experiences that create memory and attachment; poetry is required.

For example, in “Childhood: Danforth Lake” (p. 35), the poet Tom Nesbitt evokes childhood summers by a lake:

When I was younger, I slept

Through uncounted summer days,

In a log house by a lake,

And woke with lapping of the waves,

The gentlest sound.

And sunlight and shadows

Reflected on the ceiling,

As voiceless as the northern lights,

And the first restless stirring of the wind,

And my mind the blue sky.

…

And the mist-strewn lake,

And the worn boards of the rowboat

On my feet,

And the creak of the oarlocks

In the still-quiet world.

Each of these symphonic details builds a visceral experience of a place and time in childhood, of peace, and deep belonging to the earth and to water.

“Animal to Water, 2005” (p. 38), is a celebration of the freeing experience of lake swimming. The poet, Ishtar, lives with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), formerly called Chronic Fatigue Syndrome — ME is chronic, but it is so much more than fatigue — and she is sometimes home-bound, sometimes bed-bound. Because she is blind Ishtar needs the right kind of help getting into and out of the lake (“the unobtrusive aid I need”). She finds it in a friend who,

From his truck tire inner-tube

he watches for my signal that I’m done,

ready to guide me back to the shore I can’t see, can’t find.

And then

I’m sliding like a dream through water’s silky body,

…

The lake … holds its power softly.

Easy with grace, I extend my rolling spine and reach.

Precise, sleek, water fleet

I feel I’m flying

finned

…

And Mr. Body Builder of the bulked-up ego…

you are… physically formidable;

I also came from the gym,

straight from doing weights to the lake

to stalk into the middle of

an unfamiliar crowd

as an animal woman

strong, ready.

…

Let me be what I am! She exclaims, a force to be reckoned with.

…

Lake swimming is a prayer and a push for survival

that broke out of a closed box world.

Such a love letter to the blessing of swimming in sweet water.

Brian Brett writes, “I was born for water. A wounded child, I retreated to water, and have spent most of my young life near [it]. I swam like a frog with an awkward grace, a grace I didn’t know on land.”

In “Beautiful Boys” (p. 49), Brett comes into his own at the edge:

…not knowing

if I was beautiful, if I was wild,

if I was lost, or if I was just another boy.

It didn’t matter then, not on that day;

…

while the bright scroll of our lives

lay unwritten before us like a river.

What counted was the run to the edge

and the scissored,

leg-thrashing

leap into….

And from Kate Braid, who has thought a lot about the elements — see Elemental (Caitlin Press, 2018) — comes “Water to Water” (p. 55), a primordial body-memory:

…

this swimmer finds another

memory, long-forgotten motion flowing

through arms, legs, twist of her body turning

as if some ancient instruction

bubbling through her, remembered at last

…how safe and right

it feels to be a new-born, fish, alive again,

the body’s grace joined, thirst quenched,

water to water.

In “Stone’s Deep Accord, Its Steady Presence” (p. 57), Wendy Donowa articulates the life, presence and framing of stone on waterways.

Snow on stone. Crystallized for seconds, for eons,

their specific gravities meet.

Snow smokes over elk pastures

carpeting ancient inland seas

now draped above valleys.

And slate, shale’s bastard progeny, fine-grained,

foliated, its fossil traces

measuring earth’s timescales.

Compressed for millennia

by time’s upheavals, striations

sent thundering down the tilt

of layered shelves….

cobbling waterways that loop the continent.

Erosion’s runes inscribe its journey.

Stone’s deep accord, its steady presence

….

Now grounded, stone as witness, as clarification…..

while days open and close

folding into the dark.

Stone as holder, keeper of snow and ice, of rain, of water flowing over millennia, a silent witness. An epic poem that reminds us of the very long time scale of water on the earth’s surface and stone, its container and guide.

“Judd Beach” (p. 70), by Bren Simmers, a writer formerly from Vancouver and Squamish, now transplanted to Prince Edward Island, is a clever interweaving of two threads in alternating lines. Set at Judd Beach in Brackendale near Squamish, the first and alternating lines in bold are set in the present — “blurred zing of hummingbirds darting back and forth/ …banked jumps built for BMX, the loose cluster of teens.” The second and alternating lines, in paler font, live in the bigger picture, the longer time — “our blood 92% water, the river here long before we were born and long after/ animal and ancestor, the river recycled into cloud;” and “wild, feral, add your track to the wet sand: dog, coyote, eagle, parentheses of elk;” and ending with “rocks capped with snow rising like dough, the river a place of renewal, return, the source.”

As we live in the present with kids splashing, flood warnings, the river clear or cloudy, we can feel this enduring quality that outlives us and the river’s many changes.

*

Movement, the second section of Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds, focuses on the water cycle — the movement of water in streams, rivers, ice, waterfalls. From The Fundamentals of the Water Cycle: “Earth’s water is always in movement, and the natural water cycle, also known as the hydrologic cycle, describes the continuous movement of water on, above, and below the surface of the earth. Water is always changing states between liquid, vapor, and ice, with these processes happening in the blink of an eye and over millions of years.”

“Where” (p. 74), by Katherena Vermette, is a haunting poem hinting at loss and death, and the enduring memory:

not up in the groomed grass

of the pretty park (painful words describing an “unnatural” place)

not in the hilly bush

high with growth and garbage

….

not at the street where

the fake flowers faded long ago

or where the wounds open

and cry every night

….

but here near this last bend

in the river

…

here where the water licks the sky

like smoke

….

there is still tobacco

and there still is fire

here with the river

is where I will remember

The river as the keeper of memory.

“The Promise of Rivers Shanty” (p. 83), by Harold Rhenisch, is a magical incantation of place names, the old names, inhabited by creatures, artifacts and longings of the place, the things that sing out from them. The salmon reaching for stars, the footprints in volcanic ash, smoke and salmon grease alongside a river — the holy fire of names. Rhenisch speaks like a bard, casting a spell of detail, the old ways, always ringing with the “waters that flow through the Mother,/ that carry her down, that we drink, that we honour.” Lately Rhenisch has been working with elders in the Similkameen to recover the old place names in the region. This new version of the poem sings all the rivers that feed the Fraser and the Columbia watersheds.

There is the Deadman, where the stone flowed like fire,

and black Vidette Lake, at the centre of the world,

….

….There is the Fraser,

stream of pit houses and smoke shacks, draining the sap

of the sky and the silver of the moon,…

These are the waters that flow through our hands now,

that pool in our lungs and beat in our hearts, these are the waters

that fill the hollows of our foot taps in the dust of volcanoes

where the earth split and spoke fire.

These are the children of fire meeting the sea, and waves calling

and calling and calling and calling and calling

for shore. This is the shore. These are the ways

of the water. This is the water in the stone. This

is the song in the stone. This is the stone in the song.

In “Bute Inlet” (p. 95), by Zoe Landale, the poet causes us to “flinch” when we see that these strange forms in the river like “a narrow boot toe” are actually the heads of dead salmon and we are confronted with so much death, all part of the natural cycle of the salmon and the stream.

….what are these grey arrows

the size and texture of a narrow boot toe?

You flinch when you see the back–facing serrations. Teeth

Then you know: salmon noses transformed to rubber,

embers of the eyes long gone, cheek plates

giant scales. Ankle deep, they are the lavish dead. (We stop here, immersed in the watery cycle of living and dying – so many dead, which we see about the salmon but cannot see about ourselves. Such a “lavish” evocative phrase.)

You pick one up, translate detail as well your

own internal shift between before, seeing the heads’

shapes as abstraction and beautiful, and the flinch.

Being led to see closely is a form of loving. (A theme that echoes throughout the book.)

In considering “Lost Stream” (p. 99), by Fiona Tinwei Lam, it’s hard not to quote the whole poem, so as not to miss the narrative of the story. But in essence:

Forgotten one, you remember what you were:

mossy banks, fringes of fern, rivulets, riffles,

cool passage for salmon.

….

….Smothered

into park, you were culverted, diverted, yoked,

locked into pipes while we romped above.

But you refused to be choked

….

Playing fields

soak back into marsh. Bog rises through playground.

A reminder of how much we have lost, and a clarion call to daylight creeks currently in culverts and pipes, to make wild places in the middle of our “civilized grids” where salmon can swim and spawn again.

“Don River, Crossings and Expeditions” (p. 108), by Anita Lahey, is a long elegy for the Don River which runs through Toronto. As far back as the 1830s, the Don grounds a vessel in its “impassible silt” cascading from “tanneries, abattoirs, paper mills, flour mills, lumber mills, …cattle fields”. And now we live with this legacy:

That particular night heron spent

two motionless hours perched on a post

….

its grey-blue bill trained on water, head feathers

ever-so-slightly rearranged by the breeze. Mourners

in the hundreds were drifting downriver

aboard kayak, canoe, rowboat, raft, re-enacting

the Funeral for the Don. The chief keener,

mid-wail, erect in the bow, spotted

the stock-still bird. Fell

mute. The heron’s intentions

were clear. People stared.

…

A dusty labourer from the brickworks,

dragging on a smoke, a boy

felling a cedar for his latest

ingenious lean-to;…

buddy, down on his luck, come

all the way from Nova Scotia to erect

a sheet-metal shack on the flats.

This ghostly gang follows the river’s

forgotten, curlicue shoreline…

I don’t know what to tell you

about life along the Don. It troubles me

to imagine its wild, abundant, free-

flowing past…

and how..[we]..have left it

like a dirty, sodden rag.

….

A Tyee noses upstream, dodging

cigarette butts, coffee cup lids, Styrofoam

crumbs…

…This fish….

heard the Don’s muted

cough and reeled

in its current.

….it has thrown itself

on the mercy of these ragged, panting waters–

it aims for the source.

Here is the poverty of the Don’s current state and the longing to recover its long-ago wildness.

“Two O’clock Creek” (p. 130), by Bruce Hunter, is a 12-year-old boy’s introduction to the mystery of the origins of water.

All that summer couldn’t understand

…the matter-of-fact sign nailed

on a creekside spruce:

TWO O’CLOCK CREEK

–and no water anywhere.

But each afternoon, driving back, sure enough

at two o’clock, there was a creek

roaring cold under the wheels.

Finally,…I asked.

[Uncle] John smirks, swings the Ford

into the ditch and around,

a madman on his way to a holy place. (Such a great line!)

I hang on as we climb….

Over the alpine meadows…

the crowfoot of a glacier

tipped from the distant sky, a white glory…

John points to a green waterfall

spilling over its lip.

….

And I saw how a few hours of daylight

warms the ice to a trickle that becomes a torrent

in the glacier’s pit. The mystery of rivers

is that they come from somewhere

between earth and sky.

Wrung by the sun from clouds and wind.

*

Grief, the third section of Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds, mourns all that is lost, for us humans as well as other animals who live among and with sweet water, and is a call to action. The editor quotes Maude Barlow, founding member and honorary chairperson of the Council of Canadians: “Water is being depleted many, many times faster than nature can replenish it. Unlimited growth assumes unlimited resources, and this is the genesis of Ecocide. Do not listen to those who say there is nothing you can do to the very real and large social and environmental issues of our time.”

In “Yellow Deck Chair, Black-Legged Ticks, Cracked Glass in Wood Frames” (p. 152), Lorri Neilsen Glenn laments:

I am adept at the weave, the warp and woof of rage

And I dread despair. Could I,…

Learn to find beauty in devastation, in

waste? I’m no Burtynsky – opened, raw, I am flayed

by it all: oceans gagging on garbage, deformed fish,

poison running in Northern rivers….

and here, by the shore, a spring

silence in the trees like a child’s funeral.

This is despair, the suffering that comes from all the damage, the poisoning we have done to the earth and its watersheds.

“Under Western Water: Returning to Work” (p. 169), by Richard Harrison explores the aftermath of a flood of the Bow River and its effect on his books — “A piece of paper born to soak up all the meaning/ that ink can give will take a drink from any water it’s offered,/ and then it will bloat, and relieve itself of everything it held.”

And there it was, the proof: I was standing in a tiny part

of a mass of water that connected

all the cities and towns and villages along the river,

….

I was in the body of a great silent beast,

…

and the rain revealing itself at once

from behind civilization’s enormous forgetting.

In “Water Crossings” (p.177), Elena Johnson takes language from what appears to be an environmental planning document for a pipeline, which says, “The vast majority of the pipeline will be buried up to a metre underground. The only exceptions will be select water crossings where it is safer to run the pipeline above the water crossing,” and extracts the business language so we can see and hear what this means.

For example:

(The vast majority of) the pipeline will be

(buried) up to

a metre underground.

The only exceptions will be

(select) water

(crossings) where it is safer

(to run the pipeline) above

(the water crossing) .

And as the poem proceeds, the left side continues with the business narrative, while the right side reminds us what is there, what will be threatened (“small creeks/ beaver dams/ wetland complexes/ sedge marsh/ willow swamp”). The original words in the document lull us to sleep, but the poem wakes us up to our outrage.

There are many wonderful poems in this carefully curated collection about fresh water and our relationship to it. And “Peace Country” (p. 183), by Pamela Porter, is one of them. This is a story told in marvellous rhythms about a woman who goes back to the Peace Country to connect again with her aging father, from whom she has long-since been estranged. The slow, tentative reconnection, the offer of a wild horse if she can gain its trust, the staying and fixing things, seeing her father out until he dies. What’s striking about the poem is the texture of the writing and of the details sparingly chosen to evoke the place and the relationship to her father. For example:

knotting a rope halter from scrap…

When not with the horse she was in the corral nailing

the fallen boards back.

…Everywhere in that country, wild rose

tangled itself in barbed wire, and down where the creek

met the river, the canyon spilled its secrets.

The kitchen clock’s two stiffened fingers. The tractor

whose colour the wind stole…

Each noon and night he left the fist of his napkin

on the plate…

She’d stay to mend the curtains…

…and later, grown older, her hair cropped,

the axe in her hands, swift, coming down on wood

from the careless pile….

And in the kitchen she’d turn the calendar to another month,

shouting out the date for him as winter nagged the corners

of the house,…

… Yes, she thought, she would stay until

the night like a blind pulled over his face,

until like a broken road he lay down, and she

alone again in the world. A bony girl staring out across a field.

And she would know, finally, what love was. And take

a lover then,…

And is he buried under the flooded Peace River Canyon? And is she free?

Her loneliness said return, but by then the dam covered

the canyon with its dark cloth. Standing on the precipice,

she remembered everything: how once, she was a girl

who lay on her back in a barn, and the canyon filled with sky,

a sea whose fish were named sparrow, swallow, osprey, owl.

An old man opened his door and she walked in.

Here the hydrologic cycle of water — “and the canyon filled with sky,/ a sea whose fish were named sparrow, swallow, osprey…” The sky canyon filled with water, a vaporous sea which will fall on the land and start again the cycle of flowing.

And in the end:

In the days that passed she dreamt herself underwater, curtains

billowing over her bed, the willow waving in the yard.

A fine, blessed recovery, moving at the pace of seasons, of a rich life.

*

Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds ends with a section called Notes and Ecologies of Poems. This section is a wealth of relationships the poets feel to sweet water and outlines the context for each poem.

Sweet Water is a wonderful, heartfelt book with much to teach us about our relationship to fresh water, its life cycle and the threats it faces. I have been living with this book off and on for several weeks, and I have finally arrived at a place of appreciative love for our watersheds, and deep sadness for the fundamental mistakes we have made as we developed our industrial system of production. To quote Maude Barlow again, “unlimited growth assumes unlimited resources,” including inputs to the process such as trees, minerals and water; and the fantasy that outputs, including effluents, gases, heavy metals, pesticides, sludge and rubble can be offloaded into the commons without consequence and without accountability. Even as we replant trees we don’t understand what makes a forest: monoculture destroys the health-giving mycelium network underground.

As a species we are waking up to the enormity of this challenge. We really didn’t understand where these colonial-era assumptions would lead us.

I hope it will not be too late.

*

John Swanson is the author of an almost hand, beckoning, poetry and street photography from Vancouver and Paris, published by Blurb Books, San Francisco, in 2019. an almost hand, beckoning was reviewed by P.W. Bridgman. John Swanson lives in East Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “#833 A fresh water poetry anthology”

Thank you so much John and Ormsby Review for this amazing thing!

Feels good to see Yvonne Blomer doing for fresh water what she did for the ocean a few years ago in Refugium – reviewed in Ormsby #227 https://thebcreview.ca/2018/10/03/227-specific-to-the-pacific/