Seeing ‘what once was’

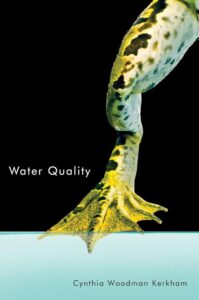

Water Quality

by Cynthia Woodman Kerkham

Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2024

$19.95 / 9780228022978

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

What struck me first about this substantial book, Cynthia Woodman Kerkham’s second (after Good Holding Ground), was the breadth and wealth of experience, places, people, and reading that she brings to her poetry. Victoria-based Woodman Kerkham is equally at ease updating classical Chinese poets, writing of family and grandchildren, and arguing with Captain Vancouver about his ‘discovery’ and naming of Desolation Sound.

As the book’s title suggests, however, her most pervasive underlying concern is with ecology and our threatened environment. It is not surprising, then, that many of her best poems are situated by a lake or in the woods and that part of their immediate appeal is the visual accuracy—“Fall, and the shy garter pops its periscopic head, / rare glide along a velvet floss of lake” or “smoke from distant forest fires gauzes a red sun.”

Doubtless many poets are as knowledgeable about the minutiae of animal and insect life as she here in is in “Along Came a spider”:

Aranea diadema. Were she human-sized her cartwheel web

would need four hundred yards of silk

To grasp such magnitude.

July sun unsticks itself from treetops.

Dragonflies zip lines of blue and black.

Fish hawk plunges, dazzles.

Six spinnerets — teats with six hundred taps —

pour five different silks, and then add glue

from two more special spouts

Author Cynthia Woodman Kerkham (photo: Maureen Reid)

For Woodman Kerkham, it’s never just the quality of the water that needs to be checked: it’s also community action, or often inaction, around dams, weirs, tree clearance, and the preservation of habitat. Most readers, I imagine, would share the values she embodies in “Dereliction,” where Old Gregory, the first settler there, claims “the lake so fully / he felt he could undo it— / could blast and dig for two years / a wide trench to siphon water downstream, / drop the lake level by ten feet / creating pasture for his sheep”—but also a thoughtless disruption of the natural order for personal gain.

Yet whereas in other hands her trained observation combined with a strong concern for the necessary balance of nature might well have led to the sort of rhetorical rant that batters us with uncomfortable ecological facts, the poet tempers this both by avoiding anything approaching rhetoric and by an understated but ever-present awareness of her own ambivalence and often complicity.

Her keen, often ironic, eye is always unsparingly critical but also self-critical in its mission to make the reader care by connecting such observations to her wider concerns, as is apparent in. “Once we were Animalcules” and “Lament of a hypocrite gardener,” where

At a cabin by a lake

I’ve left the cedars to grow,

though they drape the water view

tint green the light

sprinkling native salal.

My patch of less touched

leaves deer to wander, cougars to prowl.

The neighbours love to look

across and see what once was.

All around the shore, their squat

lawn mowers gargle and spit.

The bracing density and directness of her language—that in the title poem gives us “the thrill of cold zippers her spine” as she enters the lake and later “water gloves her body in late June” (emphasis added)—is matched by a brisk, no nonsense attitude.

If her poems about animals—otters, porpoises, seals—are affectionate they are never sentimental. Thus, despite her apparent conscientious desire, evident in “Live Trap” not to injure even wasps, “Border Control” begins: ‘Fizzle Lake reports they’ve cleaned out all breeding adult bullfrogs and juveniles after hunting for three weeks straight,” while in “Recipe for Invasive Species,” the reader is shown not only how to hunt and kill the invasive American bullfrog, but also how best to cook and eat it.

A similar sense of engagement with an endangered and vanishing world comes across when Woodman Kerkham writes about more personal memories. For instance, in “Pools” the reason for her father’s obsessive photographing of swimming pools is gradually revealed only in the third stanza—

Dipped, his heavy body felt light.

Liquid heft floating his withered leg

Shrivelled from childhood.

Pools closed to him during the polio scare.

But as is clear from “Gold Dinner Bell,” some of her most moving poems draw on her seven childhood years in a privileged Hong Kong background. “Pierced” tells how when she was six, a young Portuguese workman whose “dark curls” and the “dark silk of his forearms” she has noticed, rescues her after she has trodden on a nail and carries her home. The analogy is all the more powerful for being left implicit.

Then, too, I have read several good poems about dementia, but few as powerfully moving as “Burnt Pot, Riverbank, Indifferent Sky” about the poet’s aunt. Over three pages the poem skilfully interweaves and counterpoints the present—

… She’s a wild goat my childless aunt

coarse salt and silver-wire hair

invisible horns saddling a face

braving confusion’s squall

insisting on her moon-life

monastic home far from town …

—with the poet’s childhood memories of her much younger aunt:

She taught me to swim in Shuswap Lake, auntie who asks

me every week

where I’m calling from. Who says: I’m afraid I’ll forget

who you are.

Her hands below my spine holding me in the lake,

swirling loose limbs, making water friendly.

As with most good poetry the connections are suggested rather than stated so that the poem’s themes emerge and develop more in a musical than in a linear fashion.

Since almost all her other poems are written in the first person, I was surprised and delighted to find that, in one of the most thoroughly imagined and moving poems in the book, she adopts the persona of “Icarus’ Mother”—

Ah, Icarus, you always loved

the hum of the kick wheel

at the village kiln back on Crete,

its earthy business, the feathering of clay.

The cup our local potter helped you make,

red ribbons of coiled feldspar,

I fill with whatever is in bloom —

buttercup, field lace, wild purple lupin.

But your father had other plans.

Disdained the craftsmen,

tethered to their dirt,

their slow and patient flight

towards invention.

And then the news.

Whatever the poet’s subject or poetic form—and these include prose poem, sonnet, ghazal, haibun, and pantoum—what strikes me most is the economy of means. Woodman Kerkham’s language is spare and her characteristic tone, laconic. She doesn’t waste words setting a scene, but matter-of-factly juxtaposes scenes, events, and emotional responses in a series of notes and speculations, as here in “Backyard”:

Generations bent over earthen beds—

my sister’s beefsteak tomatoes

thick cut on buttered bread

a sprinkle if salt, of evening sun

through the kitchen window.

What would these women have done

without a garden to dig troubles deep,

turn grievance to green bean?

The end result is an impressive, well-considered, coherent, and powerful book whose emotional and linguistic subtleties reward frequent re-reading.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. The most recent of his many books of poetry is Moorings, reviewed by Trish Bowering. He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978 and was its editor for a decade; he was Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. [Editor’s note: Christopher has reviewed books by Catherine Owen, Jess Housty, Susan Musgrave, Katherine Lawrence Leanne Boschman, Isa Milman, H.C. (Hans) ten Berge, John Barton, John Pass, and Rob Taylor for BCR]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster