Using ideas as my maps

The Coincidence Problem: Selected Dispatches 1999-2022

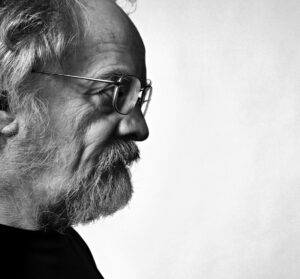

by Stephen Osborne

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2024

$24.95 / 9781551529653

Reviewed by Bill Paul

*

Stephen Osborne is a skilled writer. The co-founder of Arsenal Pulp Press and Geist magazine, he won the Vancouver Arts Award for Writing and Publishing in 2004. Osborne lives in Vancouver and has been a part of Vancouver’s literary subculture for over fifty years. His first-person essays in The Coincidence Problem are a mixture of reminiscence, observations about urban life, and reappraisals of Canadian history and culture (the First World War, rodeos, Stanley Park, Pierre Berton). With pleasure, the reader follows his trains of thoughts, his accumulation of telling details, and his ability to tell an absorbing story. Each essay is a window into a wider world; the loosely connected narratives reflect on family, friends, literary heroes, local politics, and our collective history.

In the book’s longest essay, a memorable piece titled “A Bridge in Pangnirtung,” Osborne recounts the early married life of his parents. In 1946, the couple along with forty other passengers—“two doctors, a dentist, a Film Board man, a Mountie, lots of Americans, H.B.C. men”—arrive in Churchill, Manitoba and board the Nascopie. the Hudson’s Bay Company supply ship, and set off for Baffin Island, Northwest Territories (now Nunavut). The trip takes forty days. Their destination is the Inuit village of Pangnirtung, situated in a narrow inlet near Cumberland Sound. There, Osborne’s father, a twenty-one-year-old newly minted doctor, has been assigned a position at St. Luke’s Hospital.

Osborne’s parents are full of gumption and enthusiasm. The couple reside in Pangnirtung for three years, experiencing unimaginable adventure, mystery and friendship. Owners of a fixed-focus Kodak, the two take nearly two hundred black and white photographs. The photography album is a precious keepsake. A collection of images and memories of building snow houses and riding sleds drawn by husky dogs. Part of their experience also includes the beginning of a lifelong relationship of goodwill and kindness with a local woman named Newkinga and her husband Eetowanga (an ivory carver, predictor of the weather, and interpreter of dreams). On his parents’ first day in Churchill, Osborne’s mother starts a diary. He writes:

Volume One of the diary entries concludes in a rush after the arrival in Pangnirtung, in time to send it back with the Nascopie, which lingered in the fiord for a few days before disappearing early one morning. Now the doctor’s house is seen for the first time: “The cutest little place I’ve ever seen!” and described in detail (kerosene lamps; checkerboard curtains; a fold-up bathtub); the hospital staff, the church family, the HBC family, the Mounties–all are introduced. The family of Eetowanga and his wife Newkinga, hired to support my mother and her husband, remain at this stage on the periphery of her field of vision. “Everything is perfect and I know we’ll be very happy,” she writes in the diary at the bottom of the last page.

You could say that many of Osborne’s personal essays start with an anecdote. It’s a sunny day in November, 2012 and he’s on a bus that’s headed to a neighbourhood near Vancouver’s Burrard Street Bridge. Leaving the bus he notices some street signs, maybe a park or a row of older buildings (what he calls the “random contents of public memory”). All the while he’s lost in thought. After looking at a concrete heritage building built in 1936 or maybe a commemorative plaque, he might make an observation or two—an idea will come together and off he goes, writing sentences that resemble an unbroken line of thinking, making connections between the past and the present. The writing is contemplative and at times playful, made up of carefully constructed scenes that draw meaning from that part of our history that is “beautiful, quiet and lonely and already fading away.”

The city, for Osborne, is a place to walk and explore. In “Other City, Big City,” writing about Toronto, he states: “I feel the great pleasure of strolling in great cities, of observing and being observed, of having no destination, of submitting to the monotonous, fascinating, constantly unrolling band of asphalt.” By observing and paying attention to the everyday, Osborne is reminding us to engage with the city, to look at it in different ways. In “Dynamite Quickstep,” he describes SkyTrain, Vancouver’s noisy rapid transit system. From his apartment he hears

the distant scraping-whistling sound of [SkyTrain’s] wheels on metal growing nearer, and then a moment of urgency and a dragging sound of friction, growing fainter, every few minutes a reassuring sign of urbanity, of there being a city out there in its dailiness, its patterns of destination and departure, its manifold lives.

Osborne has an interest in interpreting the lives of others, the forgotten, and the underdog. “Malcolm Lowry Expelled” is an anecdotal account of the life of Vancouver jazz musician Al Neil; and a shorter piece, “Strong Man,” is about the weightlifter Doug Hepburn, who won a gold medal at the British Empire Games in 1954. Another essay, “To the Archives,” reflects on the troubled married life of Major James Skitt Matthews, founder of the Vancouver City archives. Osborne visits the neighbourhood where Matthews and his wife lived and identifies their house as “this peaceful silent house of sadness.” Mohawk poet Pauline Johnson is remembered in “Insurgency” as a woman “writing in an age when women had no rights.” What a surprise to discover that her 1885 piece “A Cry from an Indian life” is one of the first poems written by an Indigenous person that mentions their ancestral rights to the land.

Colonialism is a theme that comes up frequently in the essays. With “Stories of the Lynching of Louis Sam,” Osborne reexamines a documented case of racial violence that took place in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley in 1884. He gives the incident some historical context and challenges the traditional narrative that Louis Sam, a teenage boy and a member of the Sto-Lo Nation, killed an unarmed man. In “Checkers with the Devil on the Kisiskatchewan,” he revisits the life of David Thompson, born in England in 1770 and at age fourteen hired to work as a clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Later, he worked as a surveyor and is credited with mapping vast areas of British North America. He was a friend of Saukamappee, a Cree, known as an honoured storyteller. For fifty-eight years Thompson was married to Charlotte Small, whose mother was Cree and her father European. After reading about Thompson’s life, this reader wanted to learn more.

What stands out in these essays is Osborne’s ability to write about history from many different angles and his skill at stitching anecdotes and ideas together to give us glimpses of what a person’s life was like. He celebrates and mourns what we have lost, mixes irony with poignant observation. In “Death at the Intersection,” an American businessman named C.F. Keiss walking near the corner of Pender and Granville in Vancouver in 1909 is knocked over and killed by a city ambulance out on a trial run. Drawing on a story from the News-Advertiser, a local newspaper from that era, Osborne writes: “Vancouver drivers of vehicles follow the British practice of keeping to the left side of the street, a practice apt to prove confusing if not dangerous to visitors from the other side of the boundary line… (Mr. Keiss having put his suitcase on his right shoulder, had unwittingly blocked his view of the oncoming traffic).”

*

East Vancouverite Bill Paul enjoys photography and reading fiction and nonfiction. [Editor’s note: Bill Paul has reviewed books by Corinna Chong, Gurjinder Basran, Caroline Adderson, William Deverell, Deryn Collier, Jann Everard, Jack Lowe-Carbell, Martin West, Dietrich Kalteis, Suzannah Showler, Curtis LeBlanc, Patrick deWitt, Barbara Fradkin, Dietrich Kalteis, Stan Rogal, Keath Fraser, and John Farrow, and contributed a photo-essay, Trevor Martin’s Vancouver, to BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster