Shadow boxing with Stan and Joe

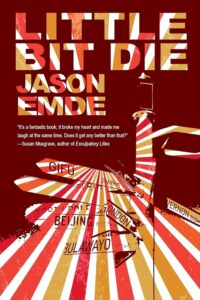

Little Bit Die

by Jason Emde

Barrie: Bolero Bird, 2023

$20.00 / 9781775330073

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Shadow boxing is a way boxers tone their muscles for a bout and suss out any gaps in rhythm. They spar with their shadows as they feel out where they will be next, in a three minute dance through a choreography of defensive and offensive jabs. Thanks to Jason Emde, it’s now also a poetic technique. As he argues, a boxing match (or one of his poems, I might add) is three minutes of living in your body.

North Okanagan-raised Emde (My Hand’s Tired and My Heart Aches) currently teaches English in Gifu, Japan, where he also has a loving wife, two sons and a house. The book says little about their world. It is a boxing ring, starkly lit, and Emde is out there on his own, punching at air, knocking his shadows out of their way.

Poetically, the book is made in short, rhythmic, repetitive jabs of defence and opportunity=against a moving target. Here, in “beijing (just as vast inside as out),” are some of those jabs as he walks us to one of his rings, Tiananmen Square:

cut out walking with Patrick past

hutong alleys, power meter mysteries,

wires tangled crazy, impossible doorways,

dim impossible lights

The point of the sport is to lay blows on your opponent’s body and mind. Always, there is dancing on your feet, ready to spring away, or back, at any time, always ready for what might come from the corner of your eye. As Emde writes of sparring with his ten-year-old son, Joe, in “boxing with Joe”: “Very light. But if he gets lazy or sloppy I’ll tap him on the forehead or belly. He needs to know.”

These are poems about men, and the male relationship that will make boys and sons into men and turn antagonistic relationships into long journeys together.

The air of these poems is not just the white space of each page, pushing back at the end of every line. It’s a body-space. And it is full of ghosts; they flood the book. There is the ghost of Tiananmen Square, for one, where bodies were crushed. A generation lost a dream there—a conception of the world as a space of increasing freedom on a Western model.

There is the ghost of Emde’s friend Stan. Stan was always in Emde’s corner, and led him shadow boxing out into the world. Theirs is a boyhood, teen, and young man’s relationship—of daring and pushing against limitations, including parental or societal ropes. Many hauntings of this kind are private moments made public, without being opened to let anyone in. Here are a couple:

Your ghost in the chorus of Take This Waltz.

in Kal Hotel saloon afternoons

giggling with me shitfaced in Roger’s closet

driving back from Penticton bookstore

It is poetry of the ordinary. The model here is Buddhist. This could be Basho. Then the greatest limitation comes. A little tap on the belly. Stan dies young.

The haunting that follows is not the terrible haunting of an unreconciled and unconsecrated spirit. It is a slow setting to rest. As the book progresses, Emde goes on a private pilgrimage through moments shared with Stan or moments he missed with him. He looks for him at the feet of the Buddha on Tiananmen Square. And he finds what is there. Himself. More and more Stan, becomes a shadow. More and more, Emde ceases to be a boy and becomes a man. It’s an old story, and it’s well told.

Another spirit here is the ghost of the city of Vernon, where Emde grew up—a beloved town known as a child knows it but not as adults do, living on not as a town but as a story. Emde travels to it, but he can never go home. The real town recedes from the storied one at the speed of life. This Vernon never grows in the imagination as Stan does. It’s the place where Stan, and the freedom and love of youth he lived and spoke for, died. He didn’t get out for good. But then, as “ghostly vernon” illustrates, neither did Emde:

Your ghost stuck in Vernon

Stan

haunting my vaults

even now

even from here

Another ghost story has Emde and his aging father make a long hiking trip through Japan with Basho’s ghost, setting the ghosts of their younger relationships aside. Yet another ghost is the ghost of the irreverent, angry young man that Emde tames as the book opens from town to friend to world to work to marriage to children. In the moments of a mind scattering in all directions, then of a sudden achieving Buddhist clarity, he takes on mantles of care, leadership and humility. Death will teach you that.

It’s a book of stillness and ripples spreading out from a dropped stone. Action here might just be a walk down a street Emde has walked a thousand times before, or through embodied memories—the poems. You don’t go anywhere in this world. You are the process of going.

In a process like that, actions settle into things. They become space. There are your hands reaching out. There is your breathing. There are your eyes, looking around for the next shadow. There is light. In this confused, almost animal glare, the poems record nouns and adjectival phrases, little testing blows against the body of a word, or the body of a past, of boys unthinkingly being their town in the world. Then, right at the end of most of the poems, there is a knockout punch that seems to come right out of the blue.

Life and death are like that, too. In “watching home movies ten years later #3,” for example, Emde conflates his son Joe’s ten years with a dedication put not at the poem’s beginning but at its end: “For Joe, who can now drag himself along.” It’s not just the infant learning to crawl, but the boy slowly evolving into a man.

At all times, though, we are shadow boxing here. There is little of any lyrical body of finely formed grammatical phrases in these poems, but there is also no jaw receiving the blow. These are soft blows on air. What is here is a dance, the work of centring a self drifting away. Neither are there enemies in this ring, and ego becomes just an illusion. The more Emde becomes alive in his body and the body of family, the more he becomes a ghost.

The poems are ghosts right along with him. They spar with you. Then they tap you on the chin. Just to keep you on your guard.

The title, Emde’s son’s mis-hearing of Paul McCartney and Wings’ “Live and Let Die,” captures that. Emde doesn’t let anything die. He holds it up, like a boxer in a clutch. Don’t let the jabs it’s made of throw you off. I think you’ll find yourself holding onto this book after it’s gone.

*

Harold Rhenisch has written thirty-five books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for a memoir, The Wolves at Evelyn. His other grasslands books are Tom Thompson’s Shack and Out of the Interior. He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and worked closely with photographer Chris Harris on Spirit in the Grass, Motherstone, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast, and The Bowron Lakes; and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan. His The Salmon Shanties: A Cascadian Song Cycle will appear this fall. Harold lives in an old Japanese orchard on unceded Syilx Territory above Canim Bay on Okanagan Lake. [Editor’s note: Harold Rhenisch has reviewed books by John Givins, DC Reid, Kim Trainor, Dallas Hunt, Tim Bowling, Hamish Ballantyne, Zoë Landale, Kerry Gilbert, Robert Hilles, Sho Yamagushiku, Bradley Peters, Aaron Tucker, Dale Tracy, Dominique Bernier-Cormier, Selina Boan, Joseph Dandurand, Délani Valin, Robert Bringhurst, Rayya Liebich, Sarah de Leeuw, Roger Farr, Stephan Torre, Don Gayton, and Calvin White for BCR. His book Landings was reviewed by Luanne Armstrong; The Tree Whisperer was reviewed by Adrienne Fitzpatrick.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Shadow boxing with Stan and Joe”

“Live and Let Die” (1973) wasn’t a Beatle’s (sic) tune. “Live and Let Die” was a Paul McCartney and Wings tune.

My bad. Corrected. —Ed.