The leap to serenity

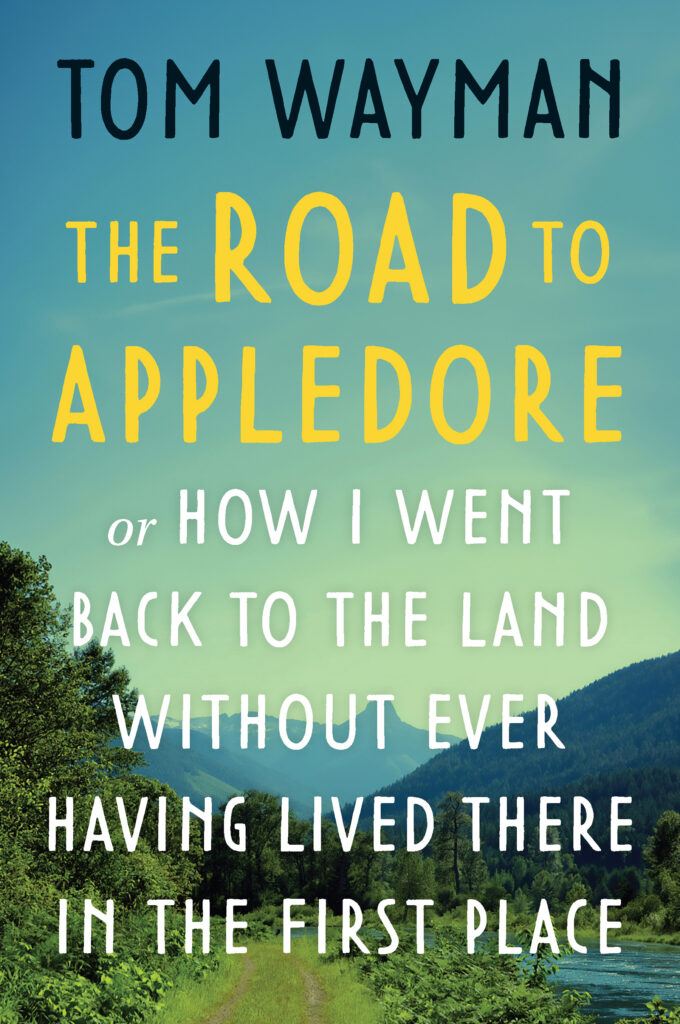

The Road to Appledore: or How I Went Back to the Land Without Ever Having Lived There in the First Place

by Tom Wayman

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2024

$26.95 / 9781990776632

Reviewed by Harvey De Roo

*

What a great subtitle! It says it all: the atavistic longing for a simpler time, when we were one with nature, with the land, before cities changed our options and who we were. Tom Wayman never lived ‘there,’ he says, but his avatar did, and was calling the writer to a more authentic life.

It began with his desire to sort things out, particularly a relationship that had become less than satisfactory, a life that had become hectic with various commitments, and poetry that needed to be re-conceived. A number of places would have done—even the cities of Edmonton or Toronto—but it took a stay in the cabin of friends in the Kootenays to hear the word. Sitting outside one day, Wayman experiences an unusual but strangely familiar feeling that he finds it hard to put a name to, until he realizes it’s happiness. Not the kind that comes from struggle and achievement, but from sitting still outdoors watching bees and ravens and hummingbirds, and feeling the breeze on his skin—the kind of zen happiness that comes from serenity in nature. In an almost animistic experience, the cabin has just spoken to him, telling him to “pay attention to what you’re doing.” The second “speaking” happens days later in a boat on the water, when a low-lying mass of cloud says, “Beauty is near, always. You only have to look.” It didn’t hurt that Wayman was high on that great back-to-the-land adjuvant, marijuana.

So, he transplants himself to a new life, a new take on things. How many of us would like to do the same if we only had the courage? The book tells of the journey up to the house Wayman bought in the Slocan Valley, his settling in and learning to live there. As the two-part rubric in the table of contents informs us: “The Destination … Is the Journey.” Appledore is not simply the stopping point of a move to a new home in the Kootenays; it is itself a journey into a new way of living and into self-understanding.

*

We approach his life in the country through his move to his new domicile, his settling in, then heading off to a conference on mountain writing, learning about the life such country offers to those who love to live there, its beauties, hardships, and perils. But the heart of the book lies in Appledore, his life on the land in a rural setting. Wayman pays close attention to the world around him, both the natural and the technical. He leads us through the daily round of gardening, of planting, maintaining, and harvesting. We are welcomed into lower gardens and kitchen gardens and the vegetables required of each. We learn of maintaining and harvesting apple trees. We learn of flowers, both in the gardens and as they adorn the rooms of his house. We learn of bears and their voracious appetites as they prepare for hibernation, proving a nuisance to the householder. All of this presented in terms of the effort and joy of living in the country through the progression of seasons, which we witness in all their beauty.

In fact, each season gets its own chapter—autumn, winter, spring, summer—interspersed with chapters with a more particular focus. The first is “Autumn”: the signs of the season—the departure of the hummingbirds, the busy harvesting of squirrels, the brief appearance of migrating birds, the changing colours of the leaves—and the requisite tasks: tucking away and mulching the garden beds, planting bulbs, pressing apples, all of autumn’s many chores, presented with meticulous detail.

“Winter” presents us with a gratifying variety of experiences and emotions: from navigating dangerous mountain roads to the joys of solitary cross-country skiing, from the exhilaration of crisp winter air to the beauty of snow-clad mountains, and a sense of gratitude for it all.

If winter brings a halt to labour on the land, spring brings it back in spades: pruning, spraying, removing mulch, fertilizing, prepping the greenhouse, buying seed, planting, purchasing and planting trees, mowing the lawn, each task graduated on a time scale in tune with the advancing season. Wayman takes living on the land seriously, expending much effort in making it a viable enterprise, living as independent a life as possible. He takes us through it all step by step, until we feel we have done the work ourselves—sitting in our armchairs with aching muscles.

Then summer. Unlike the other seasons, summer makes no dramatic entrance, so Wayman points out more subtle signs: the initial intense green of revivified trees and bush, the first vegetables from the gardens, the first rose, his first day wearing shorts. A major feature of the season in full swing is visitors, who present a variety of types: those who enjoy the out-of-doors, those who want to pitch in and help, those who just want to sit or require a tour of the Kootenays. In this section we learn that Wayman has many friends, something you might not have gathered from the earlier chapters, where people don’t figure often or long, giving the impression of a life more solitary than perhaps it is. Those who want to explore the out-of-doors are given the treat of hiking or canoeing. Because of snow melt in summer, this is the only season that allows a hike into the high terrain above the tree line, where the vistas are breathtaking, if exhausting to reach. Canoeing gets good treatment here, and features prominently in the book, making clear the fact that Wayman has become very much a denizen of this magnificent region of waterways and mountains. This makes him the ideal, and generous, guide to those visitors who don’t want to exert themselves, providing them a car-drive sweep of the area, full of resplendent vistas at every turn in the road. Summer also proves him human like the rest of us: late in the season he finally tires of all the labour the garden demands and begins to look forward to the less hectic pace of autumn.

In this chapter he discusses change—the fact of change—even in a rural community: more houses as the area increases in population; loss of certain amenities as the owners of mills or garages grow old or move away; the disappearance of the Ladas favoured by the old Doukhobor communities, or of the once ubiquitous VW vans that belonged to the counterculture crowd of the ‘60s and ‘70s; the appearance then disappearance of coffee houses, as the Starbucks craze bloomed then diminished as every restaurant came to have its own espresso machine.

*

This attention to the nitty-gritty is found also in chapters with particular focus. Take “The Elements—Low Water,” on his water problems and his attempts at solutions. This chapter delighted but did not surprise me, because no one living in the country would be surprised. I live in the Fulford Valley of Salt Spring Island and am no stranger to periodic difficulties with water supply from a gravity feed that is not always reliable or a well that doesn’t always work, or a water filtration system that can freeze and burst a pipe. “Low Water” largely features his battles with what a neighbour calls the “well from hell, involving a number of experts trying vainly to lift out the pump. The detail Wayman provides here and elsewhere gives us a real physical sense of what it’s like to live in a house in a rural setting and to go about keeping it operational. It’s not surprising that he was a key player in the poetry of the last century that concentrated on the workplace and its myriad of requirements.

One thing you learn from water problems is that your expenses don’t stop with the purchase price; living in a house isn’t cheap and if you’re going to get a house in the country, you’d better have a good chunk of money set aside. That’s also if you can find help. Where I live, we like to say that labour operates on “island time,” i.e., slow and unreliable. You often find yourself pitching in with your own toil and sweat. In the city you never think of these things. You turn on the tap and you have water, period. No hassle. Even on those rare occasions when things go wrong, as they did recently in Calgary, you don’t have to lift a finger. You can be hugely inconvenienced, yes, but the damage isn’t on your property and someone else does all the work. In the country, you’re far more vulnerable; things often go wrong and require physical effort and repair can at times be costly. Then again, there is the satisfaction of self-reliance and the goodwill of neighbours.

While such attention to detail is welcome, there are times when it is too much for this reader. Another chapter on the elements, “High Water,” provides an exhaustive description of his water gravity system. While this account proves relevant to the following narrative of conflicts and litigation, it becomes overlong. It is also hard to follow. I found the description of the distribution box impossible to visualize and felt, as I did often in the more technical areas of the book, that some illustrations would have been helpful.

On the other hand, the conflict that arises over fixing the system—a landowner not informed digging was going to occur on her property and her lawyer employing his preposterous bag of tricks—proves entertaining and reminds us that country folk, while for the most part cooperative and kind, can be ornery. Or belligerent, as one neighbour proves in illegally tapping into the community distribution box. In Wayman’s words, “there are no paradises without snakes.”

*

Another chapter features fire, how important it is to get in a supply of wood and maintain your furnace, neither of much concern to many city dwellers, who live in condos or apartments and have no idea of the hassle involved. Then there is fire as the ever-present threat of forest fire, which leads into a consideration of storms and their effects, particularly the outages of electricity they can bring on. Outages are no uncommon occurrence in rural communities, as I can attest tohere on Salt Spring, where you sometimes worry seriously about what is going to happen to your store of frozen food.

Then there is “Earth” rather a hodgepodge chapter, the most interesting part of which again deals with problems anyone in rural dwellings faces: intrusions from the wild, including a rampaging squirrel and a bear in the kitchen. The most attractive feature of this section is Wayman’s recognition of how much he belongs to Appledore, to the land, how much he loves it.

*

I was beginning to wonder how things turned out in his relationship with his long-time partner, Bea, when Wayman finally answered that question 143 pages into the book in the chapter, “Negotiating Behaviour.” Their relationship he characterizes as having been “comfortable but not satisfying.” This issue leads him to examine his own responsibility for where things stand and his behaviour more generally. The man is nothing if not thorough, given the number of relationship self-help books he reads and the counsellor he seeks out. At times it feels like self-reflection, at others, like self-absorption. Either way, it makes for a painfully honest chapter, where I see a man who wants to meet the needs of his partner but can’t. Unfortunately, nor can he honestly tell her that. Though he told their couples counselor he would like to save the relationship, he admits to us that underneath it all he really wanted out while hoping for a process painless to them both. Working through it would have required a directness he was not up for.

Not that I see his difficulty meeting her deepest needs as itself constituting failure. It’s often hard, even impossible, to meet another’s needs and be fair to your own. People’s needs can conflict, no matter how much they love each other, no matter how well-intentioned they are. Despite his desire to give, he finds it hard to do so, especially when it threatens the way he wants to live: he fears children would prove an impediment to his writing. Fair enough, for him. But it helps to be able to acknowledge this—to yourself and the other. In this regard, he comes to learn that he has had a tendency to drift and let things happen, rather than stand at the centre as an actor. This he takes steps to ameliorate by undertaking union work, and meets there a negotiator who teaches him much about successful human interaction. Finally, through the help of his counselor and the union negotiator, and much hard work at self-understanding, Wayman has come to recognize far better why he behaves as he does and to behave more constructively. He is better at facing up to things and at saying no when required. He was finally able to draw a line under his relationship with Bea. While he does not appear to have found a life partner, he has ended up happy living alone in Appledore, a wiser man than he was before.

*

I like the way Wayman pays attention to his moods and is honest in talking about them. We are given his constant awareness of his emotional response to his life in the country: a sweet sadness at mist enveloping his garden, enclosing his house, making his reduced world “a mythical place … hauntingly beautiful;” melancholy at putting the garden beds away for the approaching winter; a sense of foreboding as the settling in of winter snow grows imminent; joy at the return of hummingbirds in May. Often, he will employ wry humour, which leavens an otherwise earnest book. Nowhere more so than in the name of his property (supplied by Bea) which comes from a children’s poem by A.A. Milne. Both emotionally and physically, he shares with us a life of meaningful labour throughout the seasons as well as the strenuous outdoor pleasures he delights in. He seems made for the outdoors. I love the fact that much of his time there is spent in absolute quiet, no sounds of civilization at all—just the silence of solitude.

The book ends with the last element: air, so important to a country person, this presage of coming weather, this giver of many scents of country living: the tang of the element itself, smoke, flowers, the pungency of the land; or of birdsong and the delight of bird feeders. On it goes, this litany of life close to nature, more real, more tangible than life in the city. Wayman loves it all and conveys this love to us in a book almost more travelogue than memoir, full of sights, sounds, smells, and rural activities. Not so much other people, though. Oh, they appear, but briefly, on the periphery. He is essentially a man of solitude. But it’s a real life, intensely lived. Through this choice, this journey, he has found the road to that happiness he felt outside his friend’s cabin all those years ago. He has found the road to Appledore.

*

Harvey De Roo was a professor of Old, Middle, and Early Modern English language and literature and Old Norse language and literature in the English Department at Simon Fraser University. In the eighties he was Editor of West Coast Review. Upon retirement, he taught opera history and appreciation in the SFU seniors programme at Harbour Centre in downtown Vancouver. He was founding secretary of City Opera Vancouver and served on the board and Artistic Planning Committee for several years. He was the opera reviewer for Vancouver Classical Music (vanclassicalmusic.com) from 2014 to 2018 and lectures annually to the Vancouver Opera Club. A former resident of Vancouver’s West End and Fort Langley, he now lives on Salt Spring Island. [Editor’s note: Harvey De Roo has also reviewed books by Karim Alrawi, Jennifer Schell, D.L. Acken & Emily Lycopolus, Bill Richardson, and Jana Roerick for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “The leap to serenity”

Very fond greetings to Harvey De Roo, for whom I TA’d in the ’70s. A truly exceptional teacher & wonderful human being—never forgotten!

wow! a comprehensive review! I have long been a fan of Tom Wayman, loved his energy when he came to the old Malaspina College in Duncan many years ago…poetry readings…I bought a few of his poetry books…. I must take a closer look at this memoir at my local bookstore…Volume One in Duncan. Back to the land with all its fantasies and warts is a fascinating topic…Thanks for the review…Liz