1602 Tabouli, hummus, couscous

Arab Fairy Tale Feasts: A Literary Cookbook

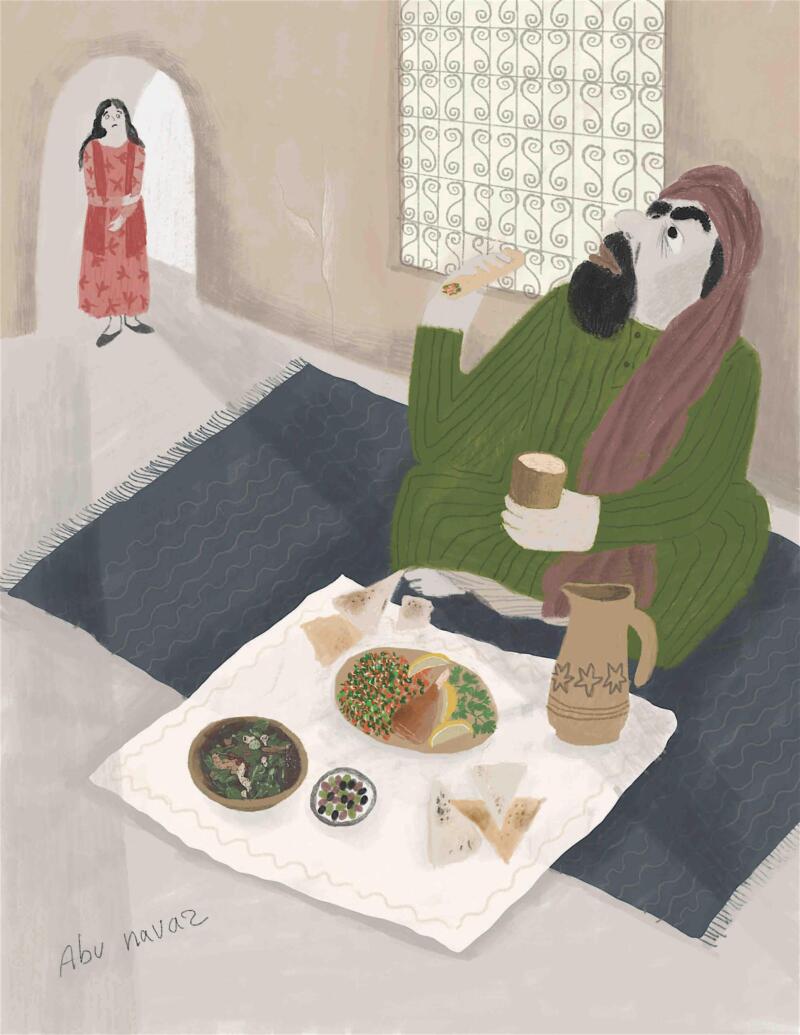

Tales by Karim Alrawi, illustrations by Nahid Kazemi, recipes by Sobhi al-Zobaidi and Tamam Qanembou-Zobaidi, and Karim Alrawi; art direction by Carol Frank, book design by Elisa Gutiérrez

Vancouver and London: Tradewind Books, 2021

$29.95 / 9781926890272

Reviewed by Harvey De Roo. Recipes tested by Harvey De Roo and Cathy Lenihan

*

KARIM ALRAWI’S Arab Fairy Tale Feasts is the latest entry in Tradewind’s delightful series, Fairy Tale Feasts — cookbooks featuring various international cuisines aimed at children — which has already achieved notable success with Jane Yolen’s books, one based on European fairytales and recipes and one on Jewish, and Paul Yee’s, on Chinese. With upcoming entries featuring Caribbean stories and cooking, and Indian, we are well into a series honouring Canada’s multiculturalism, employing the two most powerful means of connection there are: stories and food.

KARIM ALRAWI’S Arab Fairy Tale Feasts is the latest entry in Tradewind’s delightful series, Fairy Tale Feasts — cookbooks featuring various international cuisines aimed at children — which has already achieved notable success with Jane Yolen’s books, one based on European fairytales and recipes and one on Jewish, and Paul Yee’s, on Chinese. With upcoming entries featuring Caribbean stories and cooking, and Indian, we are well into a series honouring Canada’s multiculturalism, employing the two most powerful means of connection there are: stories and food.

The current offering conforms to pattern — a collection of tales, each with a simple recipe or two connected to the narrative, followed by an item of information about ingredients or elements of the story. All this in a very attractive book with utterly charming illustrations. As they should, these tales contain exotic elements — sultans and wazirs and date-sellers, names such as Malak and Salwa and Bashira, and places with names such as Oran and Kairouan and Marrakesh. Exotic, but not entirely unfamiliar to children acquainted with The Thousand and One Nights, a staple of English literature and of children’s books since Richard Burton’s late 19th-century translation. The tales are further familiarized by means of characters showing foibles common to us all, each story concluding with a moral, familiar to any kid acquainted with Aesop. Another feature drawing the reader in to a number of the tales is children outwitting adults—always a kick to child readers. There are also stories offering the pleasure of seeing rascals outwitted (and rascals outwitting).

And who better to tell these stories than a distinguished author who belongs to both worlds, honoured in each? Karim Alrawi is a human rights activist and prize-winning playwright and novelist working in both Arabic and English. He has been involved with humanitarian enterprises, major theatrical companies, and won distinguished awards. Nor is he a stranger to children’s fiction, being the author of The Girl Who Lost Her Smile, winner of Parents Magazine Gold Award 2002, and The Mouse Who Saved Egypt, listed for The People’s Prize in the UK. The illustrator, Nahid Kazemi, is herself an award-winning author and illustrator of children’s books, and a runner-up for a Governor- General’s.

*

I MUST SAY A WORD on design because of the beauty of the book. Everything is superbly thought out and executed, beginning with the two-page, verso and recto, table of contents, elegant in a light grey background and a wide left-hand margin of about a third of the page. Each entry—story and recipe titles—is set off from the others by extra leading; this and the wide margins make for an attractively clean page. Each story title sports its own colour, to be matched in its appearance later in the book. Beneath each title, in smaller, black print, is the name of the dish(es) in transliterated Arabic, followed by the English name in parentheses, and, beneath that, the Arabic name in Arabic script. Very elegant. The colour coding for the tales even extends to the title on the book’s spine, in multicoloured letters anticipating the colours in the book, an apt allusion to the multiculturalism of the series.

The two sections are echoed in the book proper: the tale first, then the recipe(s), with the addition of a third section—cultural information regarding some aspect of the recipe or the tale. Each of these three is laid out differently from its compeers. The story begins with a full-page illustration on the left-hand page and, on the right, a full page of text, with the following pages sharing text and illustration higgledy-piggledy, as dictated by the story and the whimsy of the illustrator. Each story extends from two to six pages, with three the average. The recipes start afresh, ingredients usually on the left-hand page, laid out cleanly, with instructions on the right-hand page. But there is no hard and fast rule, and pages vary. The recipes are illustrated in the same haphazard/precise manner of the tales, making the food suitably enticing and the process of cooking, fun. Kazemi’s illustrations are executed in a gentle, soft-edged, deceptively simple style, as though by a child (but with greater skill than a child could muster). The cultural info is neatly contained in boxes on their own pages (one or more), the same grey as the background of the table of contents, with a pattern across the top, like a frieze. This section is without illustration. Altogether, the design of the book is stunning, the “Feast” of the title just as easily applying to the volume’s appearance as to the stories or the recipes.

*

THE WORK OPENS with an informative piece on the origins of Arab cookbooks and the influence of Arabian cooking on European cookery. It closes telling of the nature of Arabian stories and a gracious wish for the reader’s happiness and health. The stories themselves, set in city, village, and desert, range through the Arab world of North Africa and the Middle East—Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Palestine, and more. They vary from animal fables to stories set in the home or the village or that involve travel and adventure. They are didactic, teaching us much-needed lessons, but leavened with slyness and humour. They provide a varied cast of characters comprising a microcosm of the world we all live in or encounter in books—children, mothers, wives, daughters, husbands, fathers, town gossips, students, teachers, merchants, thieves, tricksters, sultans, kings, princes, princesses, animals, even ghouls.

Alrawi clearly enjoys a sense of play. Take his openings, which he constantly varies, never using the same formula twice. There is the usual once-upon-a-time distancing, though not using those words, in such tales as “Fish Soup in Gaza,” “The Sultan and His Wazir,” “The Genie in the Sack,” and “The Dream Garden.” Then there are more unusual ones, more playful, equivocal, even—the curious indeterminacy of “Juicy Apricots”—“Once there was, or maybe not, a young girl ….” Or of “A Pot of Coins”—“They say, or so they said ….” Even more playful is the opening to “The Kindly Old Man,” exploiting a kind of zeugma—“In a time when all men had moustaches and all cats had whiskers ….,” the former believable enough and the latter, delightfully silly. Such openings tend to involve the reader, to make them work—reading as a kind of game or joint enterprise with the narrator. Then there are openings that are inclusive, forming a bond between reader and narrator—“Once long ago, there lived a little girl who was much like you or me ….” from “The Story and the Chickpeas.” Then there are those that land in medias res, no pussyfooting around, as in “Abu Nawas Tells a Tale”—“Abu Nawas had a falling out with his wife.” All these openings provide a nice variety, itself a time-honoured aesthetic pleasure.

This sense of playfulness we also find in a number of the stories. There are the clever lies the thieving girl of “Juicy Apricots” tells to fool the old gardener, with, at the end, a spur-of-the-moment save. “What about the apricots in your pocket?” the gardener asks, to which the inventive—and outlandish—reply, “Funny you should ask …. I was wondering that myself. Strange, the tricks the wind can play.” Or “Abu Nawas Tells a Story,” in which the title’s trickster character cons a woman and her husband by playing on the literal/figurative senses of Hell. Or “The Lion Repents,” as the title character, with smooth hypocrisy, cons the other animals into becoming prey and at the same time into praising his virtuous “conversion” from predator to friend. Or “Fish Soup in Gaza,” where the daughter slyly “outs” her father with a lie more outrageous than his.

So, the stories are marked by humour, by good nature. They are skillfully told, deceptively simple, getting the job done with a minimum of flourish. What description there is serves only to further the plot. The plots themselves can be straightforward, as in “Juicy Apricots,” comprising little more than the girl’s ascent up the tree, followed by her confrontation with the gardener. Others can be more devious, as in “The Lion Repents,” with its sly deception of the reader, hiding both motivation and action that would reveal what is really happening. “He decided to change his ways” proves deliciously ambiguous, as the plot is impelled by tacit elements. Only the brief remarks of the baboon and hyena hint at what is really going on. Or there is the turnabout plot, as in “A Pot of Coins,” where the main character’s intent is subverted by his own folly, and benefits those he has offended. Or the discovery plot, as in “Fish Soup in Gaza,” where at the end the reader finds out the little girl hasn’t been deceived by her father’s lies at all, but bests him at his own game. Or the revelation plot, as in “The Genie in the Sack,” where Heba outs the thief by deceiving her workers about the nature of the test. And on it goes, enough for us to know we are in the hands of a master storyteller.

This is borne out in the characterizations, which come through action or dialogue, with individuals sharply observed. With spare use of dialogue, Alrawi finely discriminates the baboon from the hyena in “The Lion Repents,” the former compassionately trying to help the foolishly trusting animals, the hyena, cruelly getting a kick out of their folly. There’s also the fine observation that the buffalo is too satisfied with his own virtue in forgiving the lion. Or there’s the clever victim, as in “The Last Supper,” where the action makes it appear that Bashira is being taken in by the gossips, only to have her turn the tables on them at the end, showing she has been on to them all along. Or characterization against expectation, as in “The Sultan and His Wazir,” in which the ghoul couple call one another ‘Sweetie Pie” and “darling” and “dear”—not what you would expect from monsters assessing the culinary suitability of their captive. So, characterization from action, deftly handled, and with wit, adding to the pleasure of these stories.

Finally, each story has in it food that will be picked up in the ensuing recipe(s), so let’s do the same and look at some of them now.

*

THANKS TO MANY Mediterranean restaurants in Western cities, a number of the dishes will be familiar—tabouli, hummus, chicken kebab, couscous—and others not so familiar. This review includes both kinds, with thirteen tested, a not ungenerous sampling of the book’s culinary offerings (twenty-three in all).

And, as it turned out, I had eager tasters. One day after a hike, several of us were sitting enjoying a beer and conversation when someone asked me what I was up to lately. I mentioned the book I was reviewing and, before I knew it, I had immediate and vociferous volunteer tasters. And, soon after, a fellow tester. When my friend Cathy heard what I was up to, she was delighted and asked if she could help cook some of the food. Having lived in Paris for many years and enjoyed Arabic hospitality, which is legendary, she is an aficionado of the cuisine. So, the first eight dishes ended up as two Arabic dinners, a week apart, in my farmhouse with eight people sitting around a candlelit table, reveling in convivial conversation (after the Covid drought) and the wonderful food. The last evening was more modest, with fewer of us around the table, but no less enthusiastic in our praise.

FIRST EVENING

Hummus bil Laban (Hummus and Yogurt Layered Dip)

Unsure of the layering of hummus, pita bits, and yogurt, we made the hummus alone, the recipe being quite standard: chickpeas, tahini, lemon juice, garlic, and salt. It was a big success, everyone praising the lemony tang (½ cup of juice for 28 oz of chickpeas). Instead of using canned chickpeas we used dried, soaked overnight, which we feel gives a superior favour. On our second evening, we made the recipe with all the ingredients called for and enjoyed the dish equally, especially the crunchiness of the crispy pita and the pine nuts. The sumac called for proved unavailable on our little island, and so we used za’atar instead. The main difference the yogurt made to the dish was to intensify the garlic (two extra cloves), always a good thing.

Tabouli (Parsley and Bulgur Salad)

Tabouli is a staple throughout the Arab world. Our recipe was both standard and tasty, including diced cucumbers and tomatoes, not always called for in this dish, but welcome visitors, in my view. Our bulgur turned out slightly al dente, which didn’t please everyone. Perhaps it was the type of bulgur we used, or the ¾ cup of water in which the ½ cup of bulgur soaked for 20 minutes, or that we went for the option of pouring off the juices from the sitting cucumber and tomatoes before adding them to the bulgur and parsley. Whatever the explanation, those of us who are tabouli aficionados rather liked it this way. We also found it benefitted from the option of more lemon juice and more salt. Altogether, it made a most satisfying salad course for our meal.

Kushary (Lentil and Noodle Hodgepodge)

Hugely popular in Egypt, this is Arab comfort food, with rice, pasta, and brown lentils, each cooked separately and then combined in a serving bowl with a cup of cooked chickpeas. The lentils call for garlic, coriander, and cumin; and the rice, for coriander and cumin, very successful combinations, both. Once mixed together, these ingredients are covered in a sauce and topped off by crispy fried onion bits.

The dish proved quite hot, too hot for kids not used to an Arabic diet, we think. The heat came from the sauce, which, besides using garlic, coriander, and cumin, called for a teaspoon of black pepper and a teaspoon of paprika, rather a lot for a base tomato sauce of a mere 14 ounces. The areas of the serving that had not been penetrated by the sauce were delicious; we thought that with less pepper and paprika this dish would be a winner for its intended audience. We enjoyed the crispy onion so much we felt we could have done with more.

Kufta Assaleyah (Honey-Glazed Meatballs)

This, our only meat dish, was the hit of the evening. How can you lose when mixing in with ground beef chopped onion and garlic, chopped parsley, ground cumin, coriander, and cinnamon? The glaze of honey and pomegranate molasses did not please everyone, but most of us felt it added a welcome piquancy to a dish already rich in flavours. A round of applause would not have been amiss, given how hard it was to find the molasses.

SECOND EVENING

Baba Ghanoush (Eggplant Dip)

This recipe, comprising the usual eggplant (3), garlic, tahini, and lemon juice, and using coriander and cumin as its spices (1 teaspoon of each), calls unusually for yogurt (1 cup), which we felt rather overpowered the delicate flavour of the vegetable. Without the yogurt, the recipe is fairly standard and would likely have produced something more to our taste.

Shorbit Adas (Simple Lentil Soup)

This was the hit of the evening. Nothing in the recipe was a surprise—a diced onion, red lentils, white pepper, and garlic—except perhaps for the teaspoon of ground cumin, which gave the dish its pleasing nutty flavour. And we took the chicken stock alternative over the water, further enriching the flavour. My dining table will see this dish again!

Arays Kufta (Lamb Puffballs)

These were also a major hit. The ground lamb—with the companionship of parsley, onion, garlic, salt, pepper, cumin, and coriander—was delicious, with the crispiness of the puff pastry in which the balls were baked an added pleasure. The dip—yogurt, diced cucumber, garlic, and salt—made a tasty complement.

Mamoul (Date-Filled Cookies)

These did not please everyone, as some complained of blandness. I liked them, myself, though they could have done with more filling (I’m a fan of richly stuffed and moist date cookies). The rosewater in the pastry was a nice touch, adding a pleasing flavour. Not everyone could identify it but all noticed and liked it.

LAST EVENING

Muhammas (Crispy Chickpeas)

This is a simple dish, with chickpeas coated with a mixture of olive oil and salt and baked, then rolled in a blend of favourite ground spices, ours being cumin and black cardamom. It made a scrumptious pre-dinner teaser, preparing us for three wonderful dishes plus a dessert.

Fattoush (Zesty Salad)

This salad—of Romaine lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, scallions, toasted pita bread, and a simple dressing of olive oil, lemon juice, and sumac—is straightforward and quite tasty. The pita, sprinkled on top, lent a delectable crunchiness. As with the hummus of the first and second evenings, we substituted za’atar for the sumac, which gave the dish its pleasing zing. In fact, we felt it could have done with more dressing than called for.

Hassa al-Samak (Fish Soup)

This soup is outstanding, with the fish (we chose cod) saturated with salt, pepper, ground cumin, and lemon juice, dredged in flour, sautéed in olive oil, then removed. A diced onion, in the same pot, is sautéed, with ground coriander stirred in as it is done. Then, minced garlic, diced tomatoes, a diced potato, a diced carrot, and a teaspoon of tomato paste. We were given the option of adding harissa, but chose not to. Then fish stock, cardamom pods, and bay leaves. After the vegetables are cooked, the fish is returned and heated thoroughly, the cardamom pods and bay leaves removed, and the remaining ingredients put through a blender. The soup that results is delicious, a real keeper, with my guests demanding the recipe.

Shish Taouk (Chicken Kebab)

The chicken, marinated in yogurt, lemon juice, olive oil, garlic, ground nutmeg, ground cardamom, salt, and black pepper, proved a real winner. We marinated it the whole day before grilling it to allow the chicken to soak in the flavour of the marinade and it was worth it, producing succulent and tender meat between pieces of bell pepper and onions.

Couscous Bilzbeeb (Couscous Pudding with Fruit and Raisins)

How can you go wrong with a couscous laden with vanilla, cardamom, ground cinnamon, dried raisins, cherries, cranberries, blueberries, figs, ground almonds and pistachios, swimming in maple syrup? It proved a delicious dessert, which one of our number suggested would make an ideal breakfast; the rest of us happily concurred.

The meal was a terrific success. By dinner’s end, Cathy was no longer happily taking photographs of various recipes, but exclaiming that she had to get a copy of the actual cookbook, an endorsement that speaks for itself.

*

ALL TOLD, the recipes were topnotch and the opportunity to test and taste them, a joy. And that’s what this book is about, after all, with its blending of stories and food, those immemorial ingredients of community, proving a most successful mix, a fine introduction to the rich cultural heritage of the Arab people.

*

Harvey De Roo was a professor of Old, Middle, and Early Modern English language and literature and Old Norse language and literature in the English Department at Simon Fraser University. In the eighties he was Editor of West Coast Review. Upon retirement, he taught opera history and appreciation in the SFU seniors programme at Harbour Centre in downtown Vancouver. He was founding secretary of City Opera Vancouver and served on the board and Artistic Planning Committee for several years. He was the opera reviewer for Vancouver Classical Music (vanclassicalmusic.com) from 2014 to 2018 and lectures annually to the Vancouver Opera Club. A former resident of Vancouver’s West End and Fort Langley, he now lives on Salt Spring Island. Editor’s note: Harvey De Roo has also reviewed books by Jennifer Schell, D.L. Acken & Emily Lycopolus, Bill Richardson, and Jana Roerick for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1602 Tabouli, hummus, couscous”