1927 Impossiblist Maverick

Class Warrior: The Selected Works of E.T. Kingsley

by Benjamin Isitt and Ravi Malhotra (eds.)

Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2022

$34.95 / 9781778290046

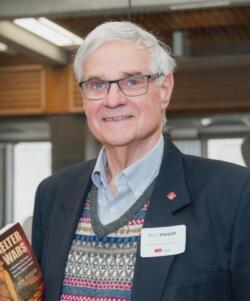

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

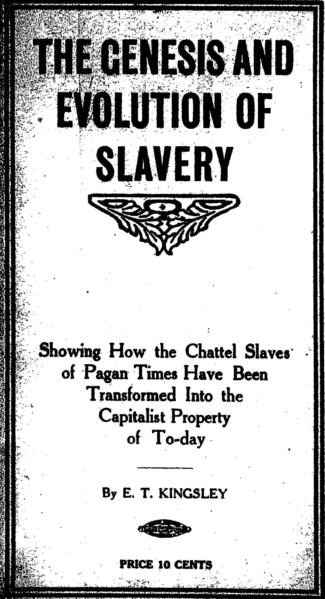

Chances are you’ve never heard of Eugene Thornton (E.T.) Kingsley. Chances are also good that if you had heard of him you might not like him or what he had to say as one of Canadian socialism’s earlier orators and the leader of the Impossiblists, a strain of thought that saw only one way to free the working class from wage slavery.

Chances are you’ve never heard of Eugene Thornton (E.T.) Kingsley. Chances are also good that if you had heard of him you might not like him or what he had to say as one of Canadian socialism’s earlier orators and the leader of the Impossiblists, a strain of thought that saw only one way to free the working class from wage slavery.

Having myself selected an obscure historical figure to profile, one that has often been shunned by other historians, I appreciated the dilemma that Benjamin Isitt and Ravi Malhotra faced in resurrecting this controversial political maverick, this “vulgar Marxist,” who was known reverentially as “the old man” among his admirers.

Once a follower of the “notoriously doctrinaire” American Socialist Labor Party founder Daniel De Leon, Kingsley became the founding leader of the Socialist Party of Canada and editor of the Western Clarion, a vital weapon in the party’s political arsenal. He also founded the short-lived Labor Star from which several selections are drawn. Both newspapers are important sources for scholars of labour and the left.

The enemies of this outspoken revolutionary no doubt outnumbered his friends. His sharp-tongue often cut into reformist politicians and labour leaders, and he regularly chastised the “enslaved working class,” demanding that they shuck off their chains and embrace the ballot box “as the only effective strike” against capitalism.

And yet here we find a well-researched and thoroughly documented record of the writings and speeches of a man who met with disagreement even within the SLP itself. As the authors point out, there was no shortage of enemies for his “unwavering focus on the ‘one-plank’ Marxist demand of overthrowing the capitalist system.”

In many ways, like my own biographical subject, this study of Kingsley’s writing may strike some readers as unnecessary, even unhelpful in understanding the genesis of the BC left. But this second book prompts renewed scholarly interest in Kingsley. The authors justify resurrecting him, arguing that “a proper, rigorous, and thorough appreciation of his ideas is beneficial.”

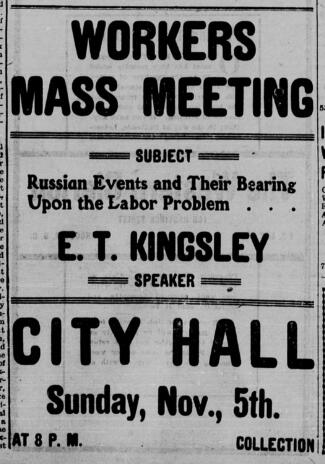

Reading his selected statements on everything from war and the Russian Revolution to Henry George’s Single Tax and the 1909 Vancouver free speech fight, we hear an angry and determined Marxist thinker lashing out at those who do not share his views on the one solution to the “labour problem.” And audiences, some of them numbering in the hundreds, loved his bombast and his combativeness.

“Resuscitating Kingsley’s ideas and those of the British Columbia school can also provide a fresh perspective to respond to current and future challenges,” argue the authors. But not everyone agrees. In fact, even in his day, trade unionists in particular took issue with his view of them as irrelevant in the fight against capitalism.

“Trade unions, whatever their leadership and orientation, were but pathetic defensive, palliative institutions,” the authors note, paraphrasing Kingsley. They are “destined to remain rooted in their capitalist confinements, always falling short of the only way of liberating their wage-dependent memberships, the laying low of capitalism itself.”

Even radical organizations like the socialist-minded One Big Union could not “alter the simple reality that, under capitalism, ‘the other fellow still owns the shop, the factory, the mill, and the mine – beyond that, he owns you.”

“‘Nothing except temporary gains . . . had ever been won by the workers in a fight for better conditions’, Kingsley declared, asserting that the only lasting solution available to the working class was “[p]olitical action . . . to strip the ruling class of power’.” Such bold language did not sit well with labour leaders like Tom Moore of the Trades and Labour Congress. Kingsley blasted “his reformist betrayals of the working class.”

The authors clearly admire Kingsley, calling him “the foremost orator and propagandist of British Columbia’s working-class movement in this era,” but they face a raft of dissenters who long ago dismissed Kingsley as a “Marxist Maverick” espousing an “impossiblist” solution to working-class inequality. Nevertheless, the authors defend Kingsley as a “working-class revolutionary” who demanded that “socialism’s making is necessarily about capitalism’s undoing.”

Isitt and Malhotra will also face criticism from contemporary leftists for Kingsley’s failure to address concerns raised by “the special oppressions of race, gender, sexual orientation and disability.” Perhaps most especially they will point to his unwillingness to address the needs of the disabled. A double-amputee, resulting from the loss of his legs in a rail accident, Kingsley remained mute on the subject, choosing instead to demonstrate his ability to fight against capitalism.

Nevertheless, Class Warrior serves as an index to the many battles on the left in BC in the first quarter of the 20th century. Kingsley’s rhetoric, mixed with the views of “Canadian Marxists of the Third Way,” as Peter Campbell dubbed men like Bill Pritchard, injected spice and vigour into the debate.

This is a brave publishing venture that adds to the growing library of biographies about Canadian radical thinkers and activists as well as providing a new source of verbatim commentary on a political philosophy that has been too deeply buried in the historical scholarship.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker. His latest book is Printer’s Devils (Caitlin Press, 2023). [Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh has recently reviewed books by Marc Edge, Bobbi Hunter (editor), BC Hydro Power Pioneers with Kerry Gold, J. Edward Chamberlin, Glen A. Mofford, and Derek Hayes for The British Columbia Review, and he has contributed an essay on trade unionist Harvey Murphy. Ron lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1927 Impossiblist Maverick”