1901 A hydro hagiography

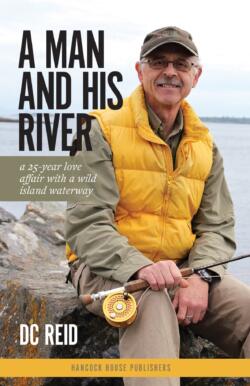

A Man and his River: A 25-year Love Affair with a Wild Island Waterway

by D.C. Reid

Surrey: Hancock House, 2022

$24.95 / 9780888397287

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

The Nitinat River, cutting through the thick jungle which separates the west coast of Vancouver Island from the majority of its inhabitants, is hardly the region’s most well-known feature. In D.C. Reid’s A Man and His River, however, it has seemingly inspired the raging emotional furor often seen among those acolytes of the Grand Canyon, the Matterhorn, or Victoria Falls. Reid makes a concerted effort to convince his readers that the Nitinat very well should be the Niagara of the west, though instead of a constant raging display of natural awe the humble Nitinat charms with its subtle drama of isolated change only perceptible to multiple returns. It is this conviction which drives Reid to put on full display the wholehearted affection which he feels for the river, leading the reader through his journey from awkward discovery to emotional ownership and technical mastery of the landscape. Self-described in its subtitle as a ‘love affair with a wild island waterway,’ A Man and His River includes the wide range of emotions which one should expect from an affair, from romantic pondering to gritty detail; paired with the technical advice only made available through focused experience, these details make for a useful and intriguing guide on how to find a fishing spot worth devoting oneself to.

The Nitinat River, cutting through the thick jungle which separates the west coast of Vancouver Island from the majority of its inhabitants, is hardly the region’s most well-known feature. In D.C. Reid’s A Man and His River, however, it has seemingly inspired the raging emotional furor often seen among those acolytes of the Grand Canyon, the Matterhorn, or Victoria Falls. Reid makes a concerted effort to convince his readers that the Nitinat very well should be the Niagara of the west, though instead of a constant raging display of natural awe the humble Nitinat charms with its subtle drama of isolated change only perceptible to multiple returns. It is this conviction which drives Reid to put on full display the wholehearted affection which he feels for the river, leading the reader through his journey from awkward discovery to emotional ownership and technical mastery of the landscape. Self-described in its subtitle as a ‘love affair with a wild island waterway,’ A Man and His River includes the wide range of emotions which one should expect from an affair, from romantic pondering to gritty detail; paired with the technical advice only made available through focused experience, these details make for a useful and intriguing guide on how to find a fishing spot worth devoting oneself to.

Reid clearly revels in walking the line between the romanticised and the real throughout his writing. While slipping in poems of his own composition at the beginnings of select chapters, and often in his sentences gliding into descriptive natural meditations, he nonetheless never shies away from the uncomfortable practicalities of spending one’s days out in the bush. Accordingly, Reid seamlessly melds descriptions of scrambling across brush and strategically dealing with bodily waste with his own sardonically nihilistic musings of God and the afterlife. This is quite fitting considering the amount of times Reid casually mentions nearly dying along and within his beloved river. The danger is nearly always coming from the river itself – during numerous encounters with bears (sometimes a mother and cub), Reid portrays a cool sensibility, but as to the Nitinat’s incessant changes and its tendency to throw car-sized trees at the author, he maintains an air of cautious and fearful respect. It is not without a few scrapes that Reid develops his bond to the river, and he describes the emotional thoughts behind that bond in full view of the reader.

In line with the ecological love affair so central to A Man and His River is the way that Reid describes both the intensity of admiration and of jealousy that comes with such a state. With deep affection Reid informs his reader of all the ins-and-outs and particularities that make the Nitinat special in his mind. However, while he shares the river’s special qualities in happiness, he also betrays a distinct anger on numerous occasions at how others misuse the locale. Reid himself, as described in the first chapter of this book, came to the Nitinat with a guide who has a described annoyance at the author’s initial inability to cope with the required fishing techniques. As his book progresses, Reid himself takes on the role of the critic in his several run-ins with stranger hobbyist fishers who fish in the wrong areas and fish in the wrong way. Oftentimes Reid’s writing gives an outlet to a boiling impatience with the inexperienced; though not necessarily to be confused with outright anger, it rather is a display of affection through the jealous desire for the river to be handled in the way it deserves.

A Man and His River therefore has multiple objectives. It is at once a celebratory book of a place which holds great importance to its author. This is evident through not only the multiple poems about the river set throughout the text, but through also the sum of its language, which dwells on both physical and emotional detail. Additionally, and not unimportantly, this book is a technical fishing guide, evidenced by the chapters dedicated to the lures and flies most useful for catching different specific fish at different specific times in different specific conditions. The exhaustive information concerning fishing the Nitinat may be translated throughout Vancouver Island. Accordingly, a third objective of A Man and his River is inspiration. The reader may very well use this book as a direct guide on the particularities of the Nitinat, and the audience may all themselves go en masse to fish that river together. However, what Reid clearly desires from his reader is form them to rather go elsewhere and form the sort of organic natural bond with any locale. In detailing the romantic and technical elements of fishing, Reid sets up the Nitinat as a gateway drug to fishing Vancouver Island generally. This is a hope that Reid offers up throughout his book; in detailing the discomforts he is willing to go through to fish this river he is advertising the addictive nature of fishing a river one has come to know. It is not simply the calming effect of fishing that seems attractive, for Reid’s writing shows him to be far too impassioned to be calm while on the river. Reid strongly shows that the dedication to catch-and-release fishing is about the development of a relationship with the river itself and its inhabitants, the fish. That relationship seems to be the end towards what Reid is working for in all his efforts at fishing.

Reid’s work, in the school of Haig-Brown, whose quotation opens up A Man and His River, is both personally compelling and informative practically. It will prove a valuable read for newcomers in search for an introductory textbook on the wonders of Island river-fishing, as well as for those more established anglers looking to revisit rural fishing from the comfort of their own home. Reid’s writing is at times raw and emotional, while having an underlying notion of developed knowledge and experience. His book radiates character, helping it to surpass the role of simply being a regional guide and become a narrative of relationship in the guise of fishing memoir.

[Editor’s note: A Man and his River: A 25-year Love Affair with a Wild Island Waterway recently was awarded the 2023 gold medal for books by the Professional Outdoor Media Association of Canada.]

*

Matthew Vernon Downey graduated in 2021 with an honours BA in History and Political Science from the University of Victoria, and in 2022 gained an MSc in international history at the London School of Economics and Political Science. After a year in Southwark, England, he is back in Victoria. Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also recently reviewed books by Alexander Globe, Angus Scully, David Giblin, Bill Arnott, Catherine Marie Gilbert, and David R. Gray for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1901 A hydro hagiography”