1823 Triumphant and melancholic

RUBYMUSIC: A popular history of women’s music and culture

by Connie Kuhns

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, March 2023

$26.00 / 9781773861012

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

As a “female bassist” myself at one time in my history and as a woman raised in a climate of continual music, whether from good ol’ CBC piped out of our kitchen radio or from the range of festivals I was taken to as a child: Vancouver Folk, Jazz, Children’s, at which I was exposed to several of the creators Connie Kuhns discusses or interviews in her compendium, from Ferron to Michelle Shocked and Lillian Allen to Rita McNeil, I’ve had a glimpse into the necessities and challenges of women both making music and seeing it made. Still, I was appalled at how many other names I didn’t know, how this history (herstory) has slid by and into obscurity in other ways, the women’s movement dispersing at its core into multiple factions that can’t agree on whether women should be singled out or not (Kuhns quoting Rosalie Goldstein, organizer of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, several times on how she disbanded the women’s stage as she believed women, “should be dispersed throughout the entire body of the festival”) or indeed, what even defines the notion of being female anymore in this gender-expanding/eroding era.

As a “female bassist” myself at one time in my history and as a woman raised in a climate of continual music, whether from good ol’ CBC piped out of our kitchen radio or from the range of festivals I was taken to as a child: Vancouver Folk, Jazz, Children’s, at which I was exposed to several of the creators Connie Kuhns discusses or interviews in her compendium, from Ferron to Michelle Shocked and Lillian Allen to Rita McNeil, I’ve had a glimpse into the necessities and challenges of women both making music and seeing it made. Still, I was appalled at how many other names I didn’t know, how this history (herstory) has slid by and into obscurity in other ways, the women’s movement dispersing at its core into multiple factions that can’t agree on whether women should be singled out or not (Kuhns quoting Rosalie Goldstein, organizer of the Winnipeg Folk Festival, several times on how she disbanded the women’s stage as she believed women, “should be dispersed throughout the entire body of the festival”) or indeed, what even defines the notion of being female anymore in this gender-expanding/eroding era.

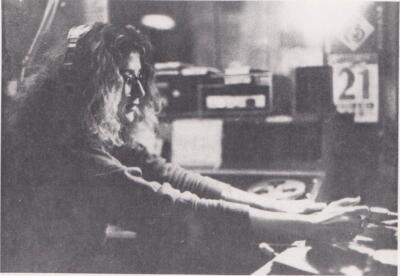

So the tone of this assemblage is both triumphant and melancholic, hearkening back to a time of real engagement with what being a woman meant in the world and how one could be seen and heard as a full and equal creator. Kuhns, as the host of CFRO’s Rubymusic program, an original half-hour show (1981-1996) featuring only women’s music, is intimately aware of the resistances to female musicians (the station wouldn’t even give her an hour at first, worried that there wouldn’t be “enough music by women” to run that length of show) and the complexities of getting their compositions heard, played and valued. She begins with a general introduction of how she shaped her opportunities as a host and interviewer, serving a crucial role in acknowledging and honouring women’s music. “Before our words are lost again,” she states ominously but accurately at the end of the preface, she wants to recollect the mostly now-deceased women who were such a key part of the 70s and 80s music scenes in Canada.

Likely the most under-celebrated female musician of that time, and the one mentioned most often in the book, is genius guitarist Ellen McIlwaine, who played with all the greats of the day from Jimi Hendrix (he asked HER to play!) to Muddy Waters, but who was always relegated to the under-paid sidelines and who ended her days as a school bus driver. In a 1984 interview, McIlwaine addressed her invisibility but gently suggested that she didn’t believe it was “intentional” but due instead to “conditioning.” Many of the other female musicians in Rubymusic are more aggravated about their exclusions, such as Nancy Gillespie (a student at SFU with me in the late 90s), bassist for SHE, who admits that being a woman make things a “little bit more difficult…we often get forgotten about, fall through the cracks of history” or Koko Taylor who adds racism to the sexism-mix and gripes how, after so many years paying those brutal dues that, “It’s been rough times…difficult. Like trying to get airplay and stuff.” Then there are fierce singers like Heather Haley of The Zellots and Jean Smith from Mecca Normal (both friends and/or one-time associates of mine in the Vancouver art scene) who want women’s music shaken up, made more raucous or weirder. As Smith asserts: “creating Mecca Normal was a reaction to the lack of bands in Vancouver. It definitely seemed like the guys were in bands and the girls watched the guys. It was annoying.” Picking up that thread of annoyance is also Rachel Melas from the band Animal Slaves who underscores how it “really annoys [her] that more women don’t go out and do it and get themselves a guitar, a bass or some drums, or whatever; and play quite loudly and aggressively.”

Well, alas, we know the answer to that one don’t we? Having been in several metal bands myself as bassist, singer, lyricist and overall creator of “the vision,” there is still forms of sexism to counter, those male musicians who won’t treat a woman on stage equally, disparaging her sometimes different relationship with her gear or the scene, who aim to diminish her with a mockery of her talents or hyper-sexualization. It’s improved in one sense, of course. There are greater numbers of women performing in all realms. But our sacrifices continue to be more evident and our challenges greater. Kuhns refuses to tiptoe around this issue. She shows how the shadows swallow women musicians if they choose to become mothers or when they inevitably age. She emphasizes the way many women have determined to turn away from patriarchal definitions all together and create women or lesbian-only musical groups and festivals (that a music session known as Hen Night used to run in the later 80s at the Railway Club was just one piece of information that took me aback in the recognition of how much things have changed – and not?)

The range of genres in Rubymusic, from Georgia Straight interviews to Geist essays, from elegiac homages to opinion pieces, makes this compendium diverse, and the breadth of time covered is also deeply educational. On occasion, as with any attempt to be inclusive, the text is overwhelmed with listings of a who’s who nature, a style that can become tedious to read. It’s a challenge to cover this many subjects and events and still maintain a narrative cogency. Yet you can read Rubymusic more temporally from cover-to-cover or utilize it more as an assemblage of historical value, to dip in as you see fit so as to recollect and to learn and to keep remembering.

As Connie Kuhns claims unswervingly in the first lines of her tribute to Bricktop in her column from 1984, “It is one of the tragedies of our culture that our heroines are often lost to us before we have a chance to learn from them.” This popular history of the often-sidelined women musicians and revolutionaries of our arts and cultural scenes during the formative times of feminism is a vital attempt to rectify our ignorance and to enable us to keep on that learning road.

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and started publishing at eleven, a short story in a Catholic Schools writing contest chapbook. She did her first public poetry readings in her teens and Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven (poems from ECW 2020) and Locations of Grief (mourning memoirs from 24 writers out from Wolsak & Wynn, 2020). She also runs Marrow Reviews on WordPress, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Hilary Peach, John Armstrong and Jason Schneider for The British Columbia Review.

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and started publishing at eleven, a short story in a Catholic Schools writing contest chapbook. She did her first public poetry readings in her teens and Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven (poems from ECW 2020) and Locations of Grief (mourning memoirs from 24 writers out from Wolsak & Wynn, 2020). She also runs Marrow Reviews on WordPress, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Hilary Peach, John Armstrong and Jason Schneider for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1823 Triumphant and melancholic”