1782 Whispers from the future

Moonlight Serenade: Embracing Aging Mindfully

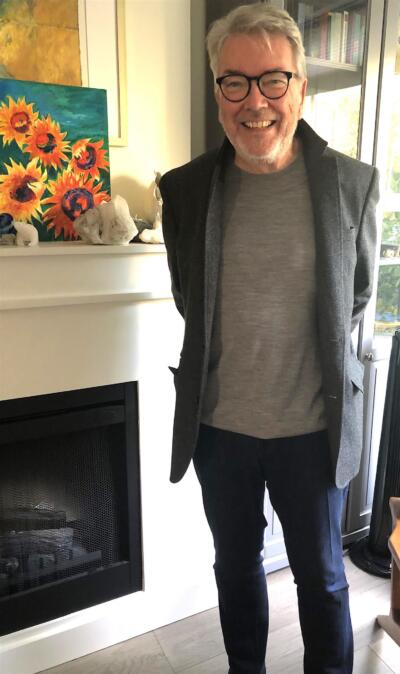

by Gordon Wallace

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2022

$28.49 / 9781039133020

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

“If not now, when?” How often do we contemplate this rhetorical refrain as we question how to live well, if not more fully, through our remaining moonlight years? The catchy refrain is frequently invoked in Moonlight Serenade: Embracing Aging Mindfully a book written by retired psychologist Gordon Wallace. If readers have not yet asked yourselves this burning question, you most certainly will as you learn to focus your attention with the mindfulness practices and program presented by Dr Wallace. This is a thoughtful and well-written book that will help readers reflect on your relationship with time, aging, traumas, and inexorable changes.

“If not now, when?” How often do we contemplate this rhetorical refrain as we question how to live well, if not more fully, through our remaining moonlight years? The catchy refrain is frequently invoked in Moonlight Serenade: Embracing Aging Mindfully a book written by retired psychologist Gordon Wallace. If readers have not yet asked yourselves this burning question, you most certainly will as you learn to focus your attention with the mindfulness practices and program presented by Dr Wallace. This is a thoughtful and well-written book that will help readers reflect on your relationship with time, aging, traumas, and inexorable changes.

Dr Wallace (whom I will call Gordon hereafter) introduces us to a group of 25 mature participants who are learning to accept and navigate challenging feelings or situations in a mindfulness program. With aging, our “unfinished emotional business,” regrets and traumas inevitably push to the surface of awareness. For readers who are contemplating issues such as legacy, dying, health limitations, memoir, and losses, or who feel the longing to live more fully while able to do so, a gentle mindfulness practice offers more confidence and resilience to move forward. My personal goal with attempting mindfulness was to resist dire stereotypes about rigid old people obstructing change. I wanted to challenge cultural attitudes that regard seniors as invisible and passive, a burden on the medical system. Or as elders isolated and stuck in the past, their lives and relationships narrowing, defined by increasing deaths with each year passing. I wanted to live each moment fully, but how?

Surprisingly, I discovered that my ability to focus and think clearly improved after practising the mindfulness exercises, some of which I will describe in this review. My caution to readers is this: Don’t be daunted by the educational structure! It is flexible and adaptable to your lifestyle. The exercises will help you, readers, respond to pain, fear, frustrations, and losses with sensitive fortitude. Mindfulness practices are simple and do-able for the most resistant readers (like myself), whether or not you feel loving or kind. Over time, doing the practices can support you to manage insecurity about your identity or belonging in a community.

Presented in an empathetic and often humorous style, the narratives in Moonlight Serenade track the 25 participants as they undergo a nine-week group program on mindfulness. So what exactly is this term that we frequently hear? Mindfulness, a term commonly used, is a cognitive skill learned to focus one’s attention. The study group’s relatable mixed reactions to learning this skill will leave struggling readers feeling seen, and heard, if not downright comforted. I was stolidly resistant! But I was willing to try. “No one gets through life unscathed” suggests the author, while reassuring us that we (questionably “old?’” people) can live with courage and full presence into the “10,000 joys and 10,000 sorrows” of life. Readers can take comfort in the now familiar motto: “If not now, when?”

The aforementioned nine week program entails structured mindful exercises that encourage you to train your mind toward self-kindness and away from aimless wandering and perseverations, aka to banish “time travel.” This may or may not appeal, particularly if you feel addicted to wandering for hours on your phone or computer. Can one learn to focus into each living moment without a screen … from moment … to moment, while overcoming unnecessary distractions? Will our bodies and brains be grateful for the attention? Mindfulness practice is an enjoyable and useful wake-up discipline, one that will appeal equally to sceptics and confirmed meditators. I realised that I had nothing to lose by practising the steps suggested. Gordon encourages readers with this appeal: “At age fifty, long-time meditators’ brains have been found to be ‘younger’ by seven and a half years compared to the brains of non-meditators of the same age” (p. 38).

“As you will recall, the definition of mindfulness is to pay attention, in the present moment, non-judgementally,” states the author (p. 103). Moonlight Serenade teaches this, with each week presenting a structured mindfulness exercise that culminates in writing a personal log or record of your experience. Gentle breath and body exercises are presented for readers to try. The author cautions: “Learning any new skill can sometimes feel artificial, forced or frustrating, so be gentle and caring with yourself … try and leave the negative judgments about any assessment of your success or failure aside for the moment” (p. 82). For me as a resistant learner, this prompt to stick to “beginner’s mind,” and to set aside judgments, was helpful. The logbook becomes a personal diary, an internal conversation attesting to one’s commitment to persevere.

Initially, my mindfulness practice was anxiously painful, until I discovered what Gordon terms “calm endurance.” In the book, this sweetly plaintive term replaces the concepts of “hopelessness” or “resignation,” which suggest that you feel stuck, failed, at a standstill. True, stuckness can feel like a hopeless state, but I much prefer “calm endurance” as offering some possibility that things can change, whether or not there is hope. “Don’t believe everything you think” becomes another slogan for mindful inquiry (p. 35).

So how did the group do? The 25 participants reported improved capacity to manage chronic pain, as well as enhanced emotional resilience with stress. People learned to relate to pain differently through cultivating trust in themselves and the world, hence improving their quality of life and relating: “Pain is a significant issue to be conscious of as you age,” Gordon notes. “The third level of response allows you to embody the process of befriending your pain. With time and practice, the pain will often slowly change and become more manageable. Yes, there may still be pain, but you learn that you can alter your relationship to it!” (pp. 183, 188).

Moonlight Serenade presents a logical and engaging compass for the heart and mind, one that is especially valuable for readers who desire to live with more kindness or compassion towards self and others (p. 367). The book and program are equally useful for those who wish to understand their roots or triggers in reacting to trauma. Readers can gradually learn mind-focusing skills while reducing risk of emotional flooding. In the wake of global disasters such as the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, or critical gaps in BC health care, or climate crises and racial oppression displacing thousands of refugees, one might have nothing to lose by trying some mindfulness practice. Mindfulness meditation and its cousin, “loving kindness” practice (which offers compassionate messages), can provide merciful disciplines to reduce harsh self-criticism and fear of the unknown, including fear of death.

Gordon notes that “anxiety is the most prevalent mental health disorder in the U.S.” (p. 43) and that “Acceptance of the aging process is typically associated with losses” (p. 123). I appreciated his Jungian approach to aging and grief, which does not try to bandage fear of old age and losses as a logistical problem to quickly fix with Botox and YouTube self-help slogans. The Jungian method involves time to dig down into yourself to embark on a life review or on a journey of discovery into one’s psyche. Often, this is catalysed by a life crisis. In mythic terms, the ground of your life quakes, a prophetic dream or nightmare may emerge, your familiar identity cracks, and the entrenched structures of selfhood or culture collapse. When this occurs, we have no choice but to engage with exiled, un-lived, or lost parts of the self. Many people opt for therapy to help. Commonly known as “the shadow” or “shadow work,” this descent into darkness (also called “the wilderness”) is popularised in mythic stories as a heroic journey, and in feminist mythology as a journey to create equitable community relations. It involves a voyage into the psyche that invites encounters with your inner monsters or angels, protectors and exiles. Warrior aspects of your deeper self emerge to help you. These lost parts can gift and guide your life, or act out through self-sabotaging behaviours and addictions. The mythic becomes psychology. Psychology in turn can support people to reach out for community beyond their individual traumas and needs.

With aging, you become aware and motivated to work on your regrets, your bucket lists, and your preparation for death. Concern may grow to understand historic or current collective traumas such as wars or forced migration, or internment of children … traumas that may have influenced your family culture. The imperative to change and become more aware grows stronger. So too does resisting it all! Some therapists describe the midlife or late-in-life “call” (or crisis), which is a call to inward reflection or self-examination, as a “whisper from the future.” In Jungian parlance, the “shadow” or “unconscious mind” calls us to embody a potentially wiser or whole self that demands to be fully explored as we age.

“To build the illusion of safety, most of us aim to create stability ‘contracts’ or personal beliefs that offer the sense of comfort and security against change,” Gordon writes. One example is defining your value by your work or by repetitive roles in intimate relationships. With aging, these contracts and roles erode. One asks “So who am I now?” (p. 95). Readers might query, “Do I really want to live each moment fully when I am age 80 or 90? Won’t I just be wasting time or be incapable of focusing, as I age?” Gordon acknowledges that it is very challenging to be fully present in each of the 54,000 seconds that comprise a waking day (p. 101), and he affirms that mindfulness can build your courage. “Of course, life can still hurt, but strengthening and enhancing your capacity to be with hurt is what mindfulness offers” (p. 35).

Gordon is eloquent with translating complex therapies into common use and sensible somatic (body) actions:

Each of us has lived a long time in this constructed life, that we believed was all there was. You have the capacity to explore, if not reshape this life of yours. It must begin with an acceptance of you, every part of you, even those parts that were unacceptable for so long…. Aging can be the gift to boldly and courageously ask: if not now, when? (p. 131).

Similar to the 12-step movement with addictions, or to cognitive behavioural therapies, many of Gordon’s approaches aim to re-script the tendency for our minds or nervous systems to dwell on shame, fears that may never happen, or negative thoughts about how unlovable we are. Mindfulness provides the timely template to do a moral inventory of your life. One begins by examining where you place your attention. I realised that much of my daily attention consists of a tsunami of busy unfocused thoughts that habitually change into self-critical attacking messages before I catch them. It was encouraging to read this directive: “The first goal of mindfulness is to learn to direct your attention when you want to, where you want it, and how long you want to retain it .…Wherever attention goes, the brain’s considerable powers follow, so in essence it is the brain’s boss” (pp. 49-50).

Readers are encouraged to create a concrete “anchor of awareness” such as to place your hand on your chest, or to focus on your breathing, or on your feet, to provide an anchor that, when you place your hand on your heart or tilt your foot, can call your attention back to the moment. “Mindfulness provides an opportunity to be more consciously aware and better appreciate the small joys that can accrue daily” (p. 151), he writes.

While Gordon suggests that deeper reflection (and questioning of your lifestyle) is an imperative of aging, he cautions against the pervasive social pressure to resist interiority. “Unfortunately, as you all are aware, our culture is not interested in having each of you meet your suffering and develop a different relationship with it” (p. 226). In response, here is my own burning question for readers:

If you had the choice to meet every moment that life presents, with non-judgement, curiosity, acceptance, quiet confidence, and ease — albeit with the caveat that this requires hard work — would you commit?

Gordon compares mindfulness practice to building a house (p. 366). The attitudes and attention that you invest in becoming aware of each moment determine the nature of the home and the environment that will support you in later years. “Mindfulness helps prepare you to fully be with whatever emotions arise, while loving-kindness practice provides a compassionate holding environment for your experience” (p. 334). He quotes sociologist Brené Brown’s work on vulnerability as important for personal and systemic change: “Meeting vulnerability is the way to increase trust within yourself, to know that you can be with whatever arises” (p. 209).

In part, Moonlight Serenade is an instruction manual that trains you to regulate your attention and attitudes. In part, it synthesises modern therapies — Jungian, cognitive, internal family systems, or somatic — into a program of self-reflective growth and integrated identities that we were too busy to achieve when we were younger. After years of office and career, I was initially resistant to a structured learning program after retirement. Freedom and unstructured time looked much more appealing. But even I, a failure at meditating, could buy into the appeal of living fully in the moment, and the slogan, ‘If not now, when?’

The book is enhanced by a website equipped with an audible set of guided instructions. The author, who is empathetic and thorough with the detailed exercises, also provides a ‘Tracking Your Practice’ log as well as structured pauses for reflection called ‘The mid-week Cuppa.’ He recommends keeping a journal to record daily gratitude as well as daily practice for time periods set by the reader and encouraged by the axiom:

The common feedback from people engaged in self-compassion practices is that it feels good when you do it and that the more you do it, the more you want to do it. Over time, a positive cycle develops, strengthening and deepening the initial motivation to practice (p. 314).

He also suggests that one keep logs of “Pleasant Events” and “Unpleasant Events” which invite reflections about the events, pains, and small joys in each day. There are exercises for mindful eating, breath-work, walking, becoming unstuck in life, and how to deal with persistently intrusive thoughts or reactions. Chapters are described in evocative language such as “Bearing The Unbearable: Mindfulness Meets Grief Practice of The Week,” “Touching the End: Mindfulness Encounters Chronic Life-Limiting Illness,” “Mindfulness Approaches the Weight and Pain of Life Practice of the Week,” with the Midweek Cuppa as “Reflections on Trust and Aging.”

Aging raises critical awareness about how we pass time. Mindfulness practice guides us through our fear of running out of time. It supports our growing needs for more spiritual or creative time. I wanted to grow what the author described as “quiet eyes,” a calm composure, and a trust that affirms, as I age, that I can navigate life’s difficulties with patience and compassion. An array of pithy quotes in Moonlight Serenade makes this prospect appealing, for example, “Forgiveness means giving up all hope for a better past” (p. 333).

I also appreciated sprinkles of poignant poetry by writers like David Whyte, Mary Oliver, and Rumi. One passage on illness and shadow work, by grief therapist Frances Weller, especially touched me:

[I]llness throws you into a ‘rough initiation.’ All initiation events throughout the ages have a common theme: it takes you into an unknown and unshaped world … in your mind is the hope of getting back to where you were before a sickness began, this is not going to happen. The roots of the word ‘recovery’ literally mean to get back something we lost’ (p. 271).

“Self compassion practice,” Gordon attests, “is primarily the cultivation of goodwill rather than good feelings. Feelings come and go, but the universal wish is to be safe, happy, healthy, and free of suffering. This is where you put your trust” (p. 321).

Despite the losses or diminishment often associated with aging, we harvest hopefulness in books such as Gordon Wallace’s Moonlight Serenade. We realise that life, aging, and dying hold possibilities that can bring joy and deeper creative expression. Readers will see themselves reflected in vignettes of grief and losses, stories of chronic pain and illness, loneliness and fear, and stories of inspiration, courage and love. Moonlight Serenade is an educational and transformative book, clearly written and with honesty and humour.

Gordon offers “attend, befriend, and surrender” as tenets or exercises to govern the quality of your mindfulness process (p. 231). Most readers will discover the exercises are practical and relatable, a manual that teaches self-compassion, or what I call “cellular kindness.” The exercises make sense when you try them. One learns to cultivate desired qualities such as non-striving, “beginner’s mind,” acceptance, trust, and non-judging. At the least, readers may emerge with less fear of aging, and more compassion and equanimity for oneself and others. For those who feel concerned about legacy or their contribution to future generations, Gordon explores the work of Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön: “… if you don’t find some way to make friends with the unknown future, which [Chödrön] characterizes as a groundlessness and the ever-changing energy of life, you will always struggle to find stability in a shifting world” (p. 91).

If the “moonlight” in the serenade represents the glow of readers living a fulfilling later life, we might also consider it as a silvery wisdom and ethical action forged from the shadows of our life experiences. Our chances for a good aging are affirmed through this mindfulness refrain: “May I and all beings be safe … may I and all beings be healthy … may I and all beings be happy … may I and all beings live with ease…” (p. 329).

If not now, when?

*

A retired clinician formerly with Nelson Mental Health, Lee Reid has written four books about BC rural and coastal communities. Her stories centre around the values and health care needs of BC seniors. Lee has also written stories about intergenerational education, rural home support care services, trauma, and dementia. Her books are: From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016), reviewed by Duff Sutherland, and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018), reviewed by Luanne Armstrong. In 2021, she self-published a fourth book, Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital: 1950-2005, which illustrates a legacy of compassionate nursing care at an historic extended care hospital in Nelson. Editor’s note: Lee Reid has recently reviewed books by Alison Acheson, Stefanie Green, Leslie A. Davidson, Phyllis Dyson, Joan Neehall, and Janie Brown for The British Columbia Review. In 2018 she contributed a popular memoir of growing up in the south of England and North Saanich, The Spider Hunters. Visit her website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1782 Whispers from the future”