1760 E.J. Hughes: the formative years

E.J. Hughes: Canadian War Artist

by Robert Amos

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2022

$35.00 / 9781771513852

Reviewed by Peter Clarke

*

Few artists have been so quintessentially identified with the West Coast as E.J. Hughes. At the time of his death in 2007 he had long been known as a reclusive figure living at Shawnigan Lake on Vancouver Island. His work for the previous half century had all been purchased by the Dominion Gallery whose director, Max Stern, promoted it throughout Canada, with steadily mounting appreciation. Such worldly success stood in bleak contrast with the circumstances of Eddie Hughes’s personal life. His wife Fern, their early married years much disrupted by the Second World War, had lost three children and herself later suffered a debilitating decline, dying in 1974. Robert Amos, who has published three earlier books on the artist, offers the grim comment: “Though Hughes never faced active combat, the anxiety of his wartime experience was relentless, and without doubt, he and his wife were shattered by the emotional strain of their life during wartime” (p. 3).

Few artists have been so quintessentially identified with the West Coast as E.J. Hughes. At the time of his death in 2007 he had long been known as a reclusive figure living at Shawnigan Lake on Vancouver Island. His work for the previous half century had all been purchased by the Dominion Gallery whose director, Max Stern, promoted it throughout Canada, with steadily mounting appreciation. Such worldly success stood in bleak contrast with the circumstances of Eddie Hughes’s personal life. His wife Fern, their early married years much disrupted by the Second World War, had lost three children and herself later suffered a debilitating decline, dying in 1974. Robert Amos, who has published three earlier books on the artist, offers the grim comment: “Though Hughes never faced active combat, the anxiety of his wartime experience was relentless, and without doubt, he and his wife were shattered by the emotional strain of their life during wartime” (p. 3).

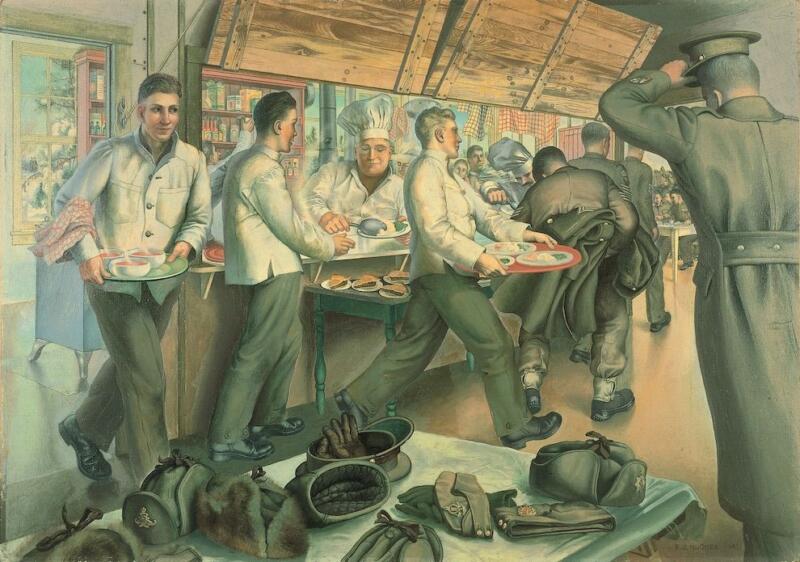

None of this sobering context is airbrushed out of the story unfolded in this book; yet it is, paradoxically, a triumphant celebration of what Hughes achieved, during formative years that nourished his talents as a painter and elevated a man of small stature (literally) into a painter whose best work has an almost iconic distinction. Its popular appeal was first established at a crucial moment in Hughes’s wartime career, when his painting “The Sergeants’ Mess” (1941) was published in all its vibrant colours across a full page of Maclean’s Magazine, then in its heyday as a widely-circulated Canadian publication. The painter was by this time already established in Ottawa, having been instituted as one of the first three Canadian “service artists” — a crucial step towards the belated establishment of the Canadian War Artists Programme at the end of 1942.

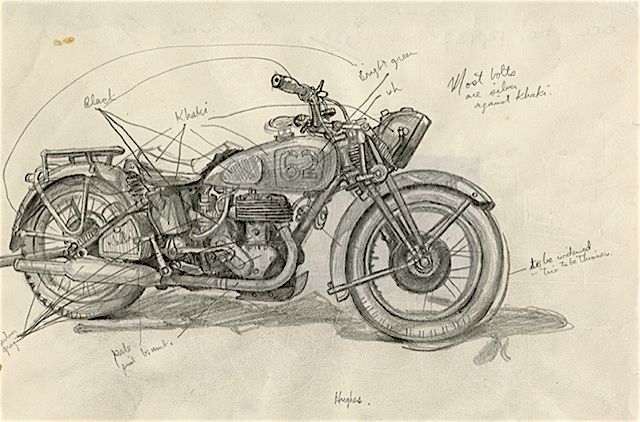

Hughes thus duly took on an officially designated role, and in fact was to become the administrative officer responsible for ultimately disbanding the operation — “the longest serving of all the war artists”, as Amos can duly claim (p. 168). But it is not, of course, in such bureaucratic terms that Hughes’s achievements should be measured. Instead, it is his paintings that themselves combine a technical mastery of military punctilio, in their attention to detail, with a flair and insight that still resonates today. Thus the sheer vigour of the sergeants’ mess still jumps off the page eighty years later; likewise, more sombre insights still invest the paintings that Hughes executed after enduring punishing fieldwork in their preparation.

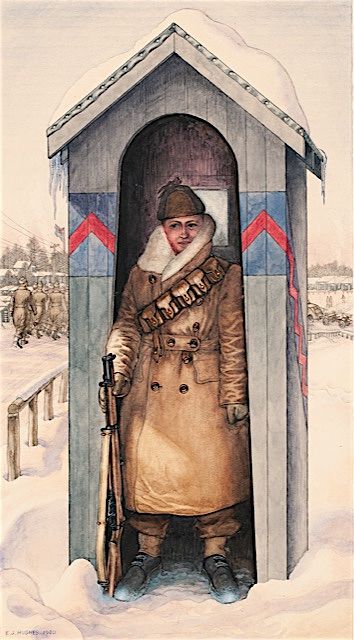

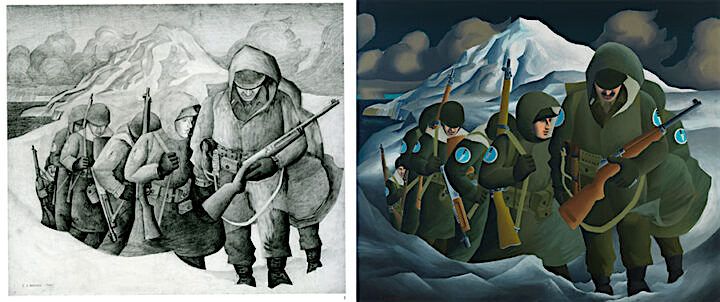

I was particularly struck by the lesser-known work that he did after his months of service in the Aleutian Islands in 1943-4, alongside the American forces. Here, in a bleak sub-arctic terrain, contesting the control of barren islands from which the Japanese were belatedly dislodged, Hughes found the materials for his sketches, which could subsequently be transformed into studio paintings. “My biggest job was hanging on to my sketch pad in the 100-mile per hour winds, called Wiliwaws,” he recalled in later years (p. 132).

The authenticity of Hughes’s work, time and again, lies in the tension between his broad visualisation of a coherent scene and his unrelenting attention to the discipline of mundane detail in conveying it. Sometimes the result has a sort of folksy charm in the figures depicted, sometimes a sweeping grandeur in his landscapes — often best of all when both aspects are juxtaposed. The high standards of reproduction achieved in the publication of this book notably assist the author in conveying his own admiration for Hughes’s work. There is undeniably a dark side to the story it tells of the personal impact of war upon Eddie and Fern; this is no bland triumphal record but a chiaroscuro that captures a fitting sense of light and shade. Above all, it reinforces our sense that Hughes’s legacy as an artist remains serious, secure and formidable.

*

Peter Clarke was formerly a professor of modern history and Master of Trinity Hall at Cambridge University. He has been a contributor to the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books and the Financial Times. His books include Mr Churchill’s Profession (2012), Keynes: The Twentieth Century’s Most Influential Economist (2009), The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire (2007), and the acclaimed final volume of the Penguin History of Britain, Hope and Glory, Britain 1900-2000 (2004). He lives with his wife, the Canadian writer Maria Tippett, in Cambridge, England, and Pender Island, British Columbia. Editor’s note: Peter Clarke has also reviewed books by Laura Bradbury & Rebecca Wellman and Allen Packwood in The British Columbia Review, and his book The Locomotive of War: Money, Empire, Power, and Guilt (Bloomsbury, 2017) was reviewed here by Stan Markotich.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster